library(tidyverse)

library(beyonce)

library(brms)

library(patchwork)

library(tidybayes)

library(bayesplot)

library(metRology)16 Metric-Predicted Variable on One or Two Groups

In the context of the generalized linear model (GLM) introduced in the previous chapter, this chapter’s situation involves the most trivial cases of the linear core of the GLM, as indicated in the left cells of Table 15.1 (p. 434), with a link function that is the identity along with a normal distribution for describing noise in the data, as indicated in the first row of Table 15.2 (p. 443). We will explore options for the prior distribution on parameters of the normal distribution, and methods for Bayesian estimation of the parameters. We will also consider alternative noise distributions for describing data that have outliers. (Kruschke, 2015, pp. 449–450)

Although I agree this chapter covers the “most trivial cases of the linear core of the GLM”, Kruschke’s underselling himself a bit, here. In addition to “trivial” Gaussian models, Kruschke went well beyond and introduced robust Student’s \(t\) modeling. It’s a testament to Kruschke’s rigorous approach that he did so so early in the text. IMO, we could use more robust Student’s \(t\) models in the social sciences. So heed well, friends.

16.1 Estimating the mean and standard deviation of a normal distribution

The Gaussian probability density function follows the form

\[p(y \mid \mu, \sigma) = \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp \left (-\frac{1}{2} \frac{(y - \mu)^2}{\sigma^2} \right ),\]

where the two parameters to estimate are \(\mu\) (i.e., the mean) and \(\sigma\) (i.e., the standard deviation). If you prefer to think in terms of \(\sigma^2\), that’s the variance. In case is wasn’t clear, \(\pi\) is the actual number \(\pi\), not a parameter to be estimated.1s

1 I point this out because sometimes you see statisticians refer to probabilities from the binomial distribution as \(\pi\).

In the text, Kruschke referred to the \(\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi}\) portion of the equation as \(Z\), and called it a normalizer. This sets the stage to make to points down the road. The first is we sometimes talk in terms of the \(Z\) distribution, and Kruschke likes to refer to standardized coefficients as \(\zeta\)s, rather than \(\beta\)s. The other point is we sometimes express model quantities with standardized effect sizes, and the whole standardization issue has a connection to the \(Z\) distribution.

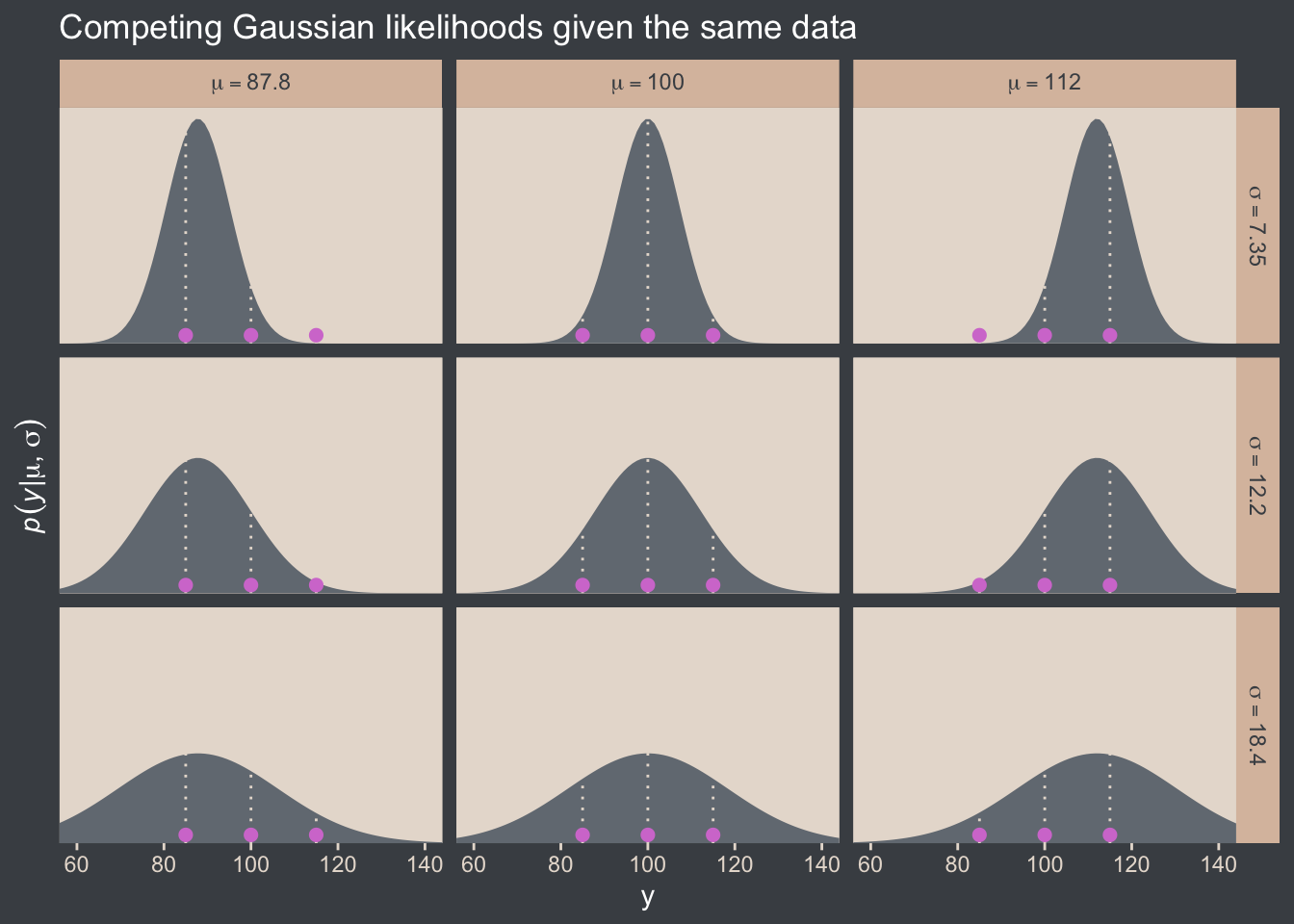

We’ll divide Figure 16.1 into data and plot steps. First we load the primary packages.

I came up with the primary data like so:

d <- crossing(y = seq(from = 50, to = 150, length.out = 100),

mu = c(87.8, 100, 112),

sigma = c(7.35, 12.2, 18.4)) |>

mutate(density = dnorm(y, mean = mu, sd = sigma),

mu = factor(mu, labels = str_c("mu==", c(87.8, 100, 112))),

sigma = factor(sigma, labels = str_c("sigma==", c(7.35, 12.2, 18.4))))

head(d)# A tibble: 6 × 4

y mu sigma density

<dbl> <fct> <fct> <dbl>

1 50 mu==87.8 sigma==7.35 9.80e- 8

2 50 mu==87.8 sigma==12.2 2.69e- 4

3 50 mu==87.8 sigma==18.4 2.63e- 3

4 50 mu==100 sigma==7.35 4.85e-12

5 50 mu==100 sigma==12.2 7.37e- 6

6 50 mu==100 sigma==18.4 5.40e- 4Instead of putting the coordinates for the three data points in our d tibble, I just threw them into their own tibble in the geom_point() function.

Okay, let’s talk color and theme. For this chapter, we’ll take our color palette from the beyonce package (Miller, 2021). As one might guess, the beyonce package provides an array of palettes based on pictures of Beyoncé. The origins of the palettes come from https://beyoncepalettes.tumblr.com/. Our palette will be #126.

beyonce_palette(126)

bp <- beyonce_palette(126)[]

bp[1] "#484D53" "#737A82" "#A67B6B" "#DABFAC" "#E7DDD3" "#D47DD2"

attr(,"number")

[1] 126Our overall theme will be based on the default ggplot2::theme_grey().

theme_set(

theme_grey() +

theme(text = element_text(color = "white"),

axis.text = element_text(color = beyonce_palette(126)[5]),

axis.ticks = element_line(color = beyonce_palette(126)[5]),

legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.box.background = element_rect(fill = beyonce_palette(126)[5],

color = "transparent"),

legend.key = element_rect(fill = beyonce_palette(126)[5],

color = "transparent"),

legend.text = element_text(color = beyonce_palette(126)[1]),

legend.title = element_text(color = beyonce_palette(126)[1]),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = beyonce_palette(126)[5],

color = beyonce_palette(126)[5]),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = beyonce_palette(126)[1],

color = beyonce_palette(126)[1]),

strip.background = element_rect(fill = beyonce_palette(126)[4]),

strip.text = element_text(color = beyonce_palette(126)[1]))

)Here’s Figure 16.1.

d |>

ggplot(aes(x = y)) +

geom_area(aes(y = density),

fill = bp[2]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = c(85, 100, 115),

color = bp[5], linetype = 3) +

annotate(geom = "point",

x = c(85, 100, 115), y = 0.002,

color = bp[6], size = 2) +

scale_y_continuous(expression(italic(p)(italic(y)*"|"*mu*", "*sigma)),

breaks = NULL, expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

ggtitle("Competing Gaussian likelihoods given the same data") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(60, 140)) +

facet_grid(sigma ~ mu, labeller = label_parsed)

Here’s how you might compute the \(p(D \mid \mu, \sigma)\) values and identify which combination of \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) returns the maximum value for the data set.

crossing(y = c(85, 100, 115),

mu = c(87.8, 100, 112),

sigma = c(7.35, 12.2, 18.4)) |>

mutate(density = dnorm(y, mean = mu, sd = sigma)) |>

group_by(mu, sigma) |>

summarise(`p(D|mu, sigma)` = prod(density)) |>

ungroup() |>

mutate(maximum = `p(D|mu, sigma)` == max(`p(D|mu, sigma)`))# A tibble: 9 × 4

mu sigma `p(D|mu, sigma)` maximum

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl>

1 87.8 7.35 0.0000000398 FALSE

2 87.8 12.2 0.00000172 FALSE

3 87.8 18.4 0.00000271 FALSE

4 100 7.35 0.00000248 FALSE

5 100 12.2 0.00000771 TRUE

6 100 18.4 0.00000524 FALSE

7 112 7.35 0.0000000456 FALSE

8 112 12.2 0.00000181 FALSE

9 112 18.4 0.00000277 FALSE That is, this is a code instantiation of when Kruschke wrote:

The probability of the entire set of independent data values is the multiplicative product, \(\prod_i p(y_i \mid \mu, \sigma) = p(D \mid \mu, \sigma)\), where \(D = \{y_1, y_2, y_3\}\). (p. 450)

The combination of mu == 100 and sigma == 12.2 had the maximum value, or otherwise put, the most credible combination of candidate data-generating population parameters for the normal distribution, given the three data points in the y vector.

16.1.1 Solution by mathematical analysis Heads up on precision

Not much for us, here. But we might reiterate that sometimes we talk about the precision of the normal distribution (see page 453), which is the reciprocal of the variance (i.e., \(\frac{1}{\sigma^2}\)). As we’ll see, the brms package doesn’t use priors parameterized in terms of precision, and nor does Stan, which is the computational engine on which brms is based. But JAGS does, which means we’ll need to be able to translate Kruschke’s precision-laden JAGS code into \(\sigma\)-oriented brms code in many of the remaining chapters.

Proceed with caution.

16.1.2 Approximation by MCMC in JAGS HMC in brms

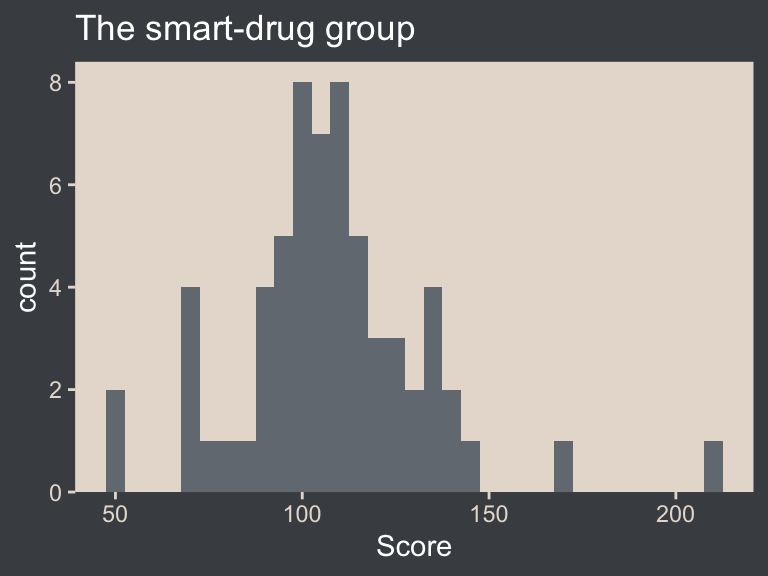

Let’s load and glimpse() at the TwoGroupIQ.csv data.

my_data <- read_csv("data.R/TwoGroupIQ.csv")

glimpse(my_data)Rows: 120

Columns: 2

$ Score <dbl> 102, 107, 92, 101, 110, 68, 119, 106, 99, 103, 90, 93, 79, 89, 137, 119, 126, 110, 71, 114, 100, 95, 91, 99, 97, 1…

$ Group <chr> "Smart Drug", "Smart Drug", "Smart Drug", "Smart Drug", "Smart Drug", "Smart Drug", "Smart Drug", "Smart Drug", "S…The data file included values from two groups.

my_data |>

distinct(Group)# A tibble: 2 × 1

Group

<chr>

1 Smart Drug

2 Placebo Kruschke clarified that for the following example, “the data are IQ (intelligence quotient) scores from a group of people who have consumed a ‘smart drug’” (p. 456). That means we’ll want to subset the data.

my_data <- my_data |>

filter(Group == "Smart Drug")It’s a good idea to take a look at the data before modeling.

my_data |>

ggplot(aes(x = Score)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 5, fill = bp[2]) +

scale_y_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

ggtitle("The smart-drug group")

Here are the mean and standard deviation of the Score values.

(mean_y <- mean(my_data$Score))[1] 107.8413(sd_y <- sd(my_data$Score))[1] 25.4452The values of those sample statistics will come in handy in just a bit.

If we want to pass user-defined values into our brm() prior code, we’ll need to define them first in using the brms::stanvar() function.

stanvars <- stanvar(mean_y, name = "mean_y") +

stanvar(sd_y, name = "sd_y")It’s been a while since we used stanvar(), so we should review. Though we’ve saved the object as stanvars, you could name it whatever you want. The main trick is to tell brms about your values with the stanvars argument within brm().

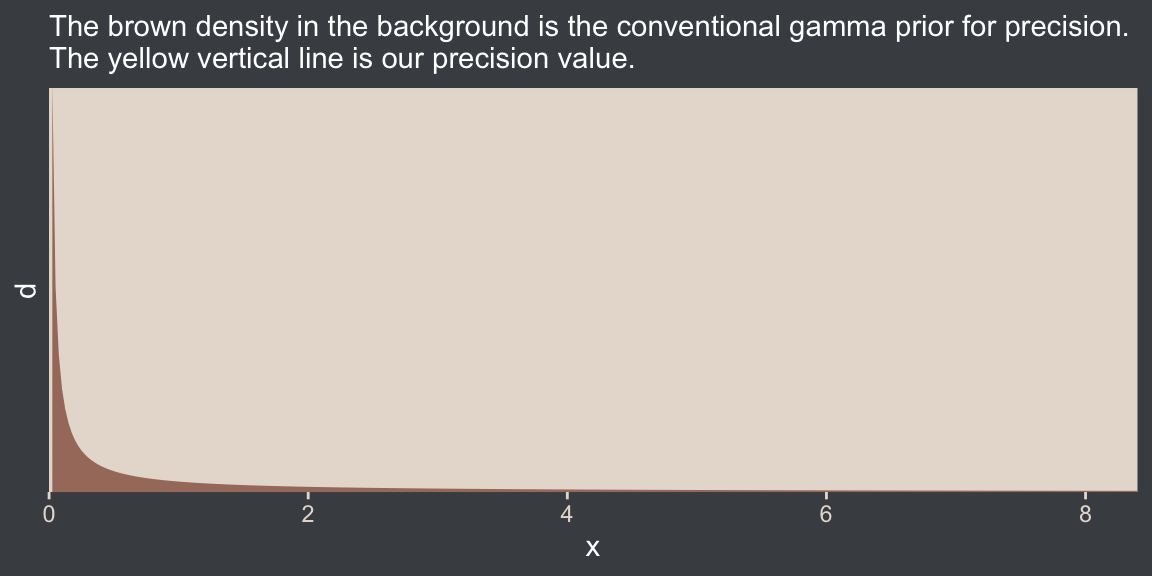

Kruschke mentioned that the “the conventional noncommittal gamma prior [for the precision] has shape and rate constants that are close to zero, such as Sh = 0.01 and R = 0.01” (p. 456). Here’s what that looks like.

tibble(x = seq(from = 0, to = 12, by = 0.025)) |>

mutate(d = dgamma(x, shape = 0.01, rate = 0.01)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d)) +

geom_area(fill = bp[3]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 1 / sd_y^2, color = bp[5], linetype = 2) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

scale_y_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05)), breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "The brown density in the background is the conventional gamma prior for precision.\nThe yellow vertical line is our precision value.") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 8),

ylim = c(0, 0.35))

The thing is, with brms we typically estimate \(\sigma\) rather than precision. Though gamma is also a feasible prior distribution for \(\sigma\), we won’t use it here. But we won’t be using Kruschke’s uniform prior, either. The Stan team discourages uniform priors for variance parameters, such as our \(\sigma\). I’m not going to get into the details of why, but you’ve got that hyperlink above and the good old Stan user’s guide (Stan Development Team, 2022) if you’d like to dive deeper.

Here we’ll use the half normal. By “half normal,” we mean that the mean is zero and it’s bounded from zero to positive infinity, which means no negative \(\sigma\) values for us! By the “half normal,” we also mean to suggest that smaller values are more credible than those approaching infinity. When working with unstandardized data, an easy default for a weakly-regularizing half normal is to set the \(\sigma\) hyperparameter (i.e., S) to the standard deviation of the criterion variable (i.e., \(s_Y\)). Here’s what that looks like for this example.

tibble(x = seq(from = 0, to = 110, by = 0.1)) |>

mutate(d = dnorm(x, mean = 0, sd = sd_y)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d)) +

geom_area(fill = bp[3]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = sd_y, color = bp[5], linetype = 2) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

scale_y_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05)), breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "The brown density in the background is the half-normal prior for sigma.\nThe dashed yellow vertical line is our 'sd_y' value.") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 100))

This prior isn’t quite as non-committal as the conventional gamma prior for precision. However, it will discourage the HMC algorithm from exploring \(\sigma\) values much larger than two or three times the standard deviation in the data themselves. In practice, I’ve found it to have a minimal influence on the posterior. If you’d like to make it even less committal, try setting that \(\sigma\) hyperparameter to some multiple of \(s_Y\) like \(2 \times s_Y\) or \(10 \times s_Y\). Compare this to Kruschke’s recommendations for setting a noncommittal uniform prior for \(\sigma\). When using the uniform distribution, \(\operatorname{Uniform}(L, H)\),

we will set the high value \(H\) of the uniform prior on \(\sigma\) to a huge multiple of the standard deviation in the data, and set the low value \(L\) to a tiny fraction of the standard deviation in the data. Again, this means that the prior is vague no matter what the scale of the data happens to be. (p. 455)

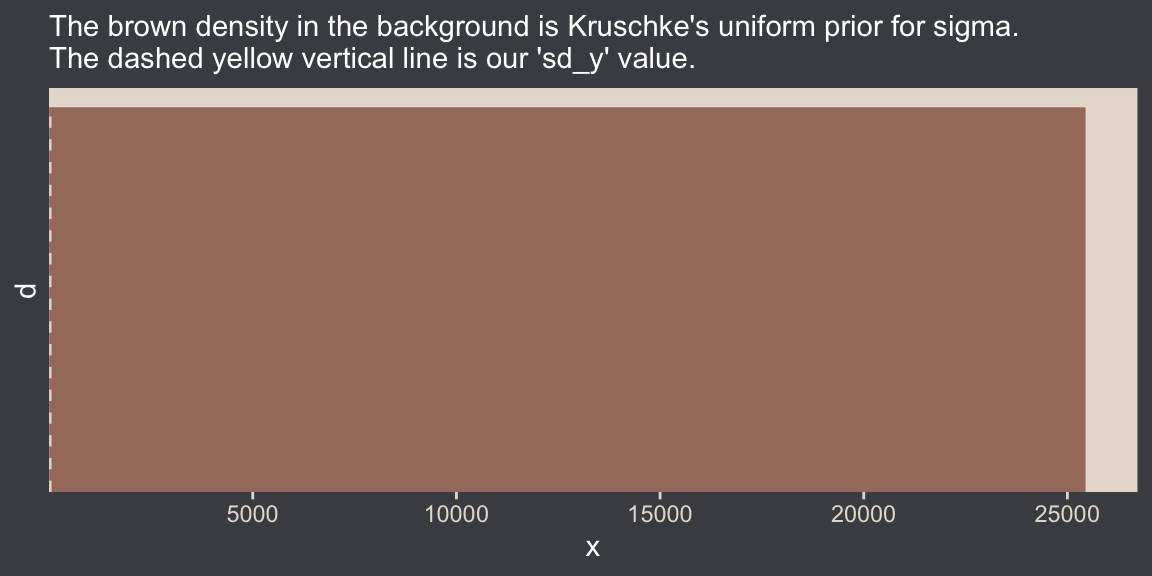

On page 456, Kruschke gave an example of such a uniform prior with the code snip dunif( sdY/1000 , sdY*1000 ). Here’s what that would look like with our data.

tibble(x = c(sd_y / 1000, sd_y * 1000)) |>

mutate(d = dunif(x, min = sd_y / 1000, max = sd_y * 1000)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d)) +

geom_area(fill = bp[3]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = sd_y, color = bp[5], linetype = 2) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

scale_y_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05)), breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "The brown density in the background is Kruschke's uniform prior for sigma.\nThe dashed yellow vertical line is our 'sd_y' value.") +

coord_cartesian()

That’s really noncommittal. I’ll stick with my half normal. You do you. Kruschke had this to say about the prior for the mean:

In this application we seek broad priors relative to typical data, so that the priors have minimal influence on the posterior. One way to discover the constants is by asking an expert in the domain being studied. But in lieu of that, we will use the data themselves to tell us what the typical scale of the data is. We will set \(M\) to the mean of the data, and set \(S\) to a huge multiple (e.g., \(100\)) of the standard deviation of the data. This way, no matter what the scale of the data is, the prior will be vague. (p. 455)

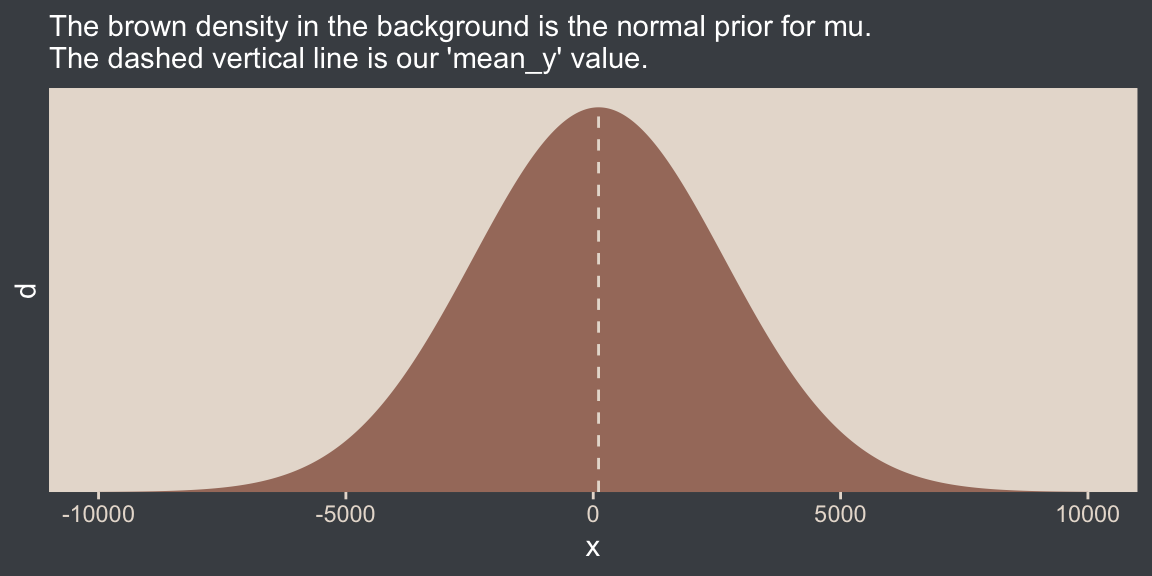

In case you’re not following along closely in the text, we often use the normal distribution for the \(\beta\) parameters in a simple regression model. By \(M\) and \(S\), Kruschke was referring to the \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) parameters of the normal prior for our intercept (\(\beta_0\)). Here’s what that prior looks like in this data example.

tibble(x = seq(from = -10000, to = 10000, by = 10)) |>

mutate(d = dnorm(x, mean = mean_y, sd = sd_y * 100)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d)) +

geom_area(fill = bp[3]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean_y, color = bp[5], linetype = 2) +

scale_y_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05)), breaks = NULL) +

labs(subtitle = "The brown density in the background is the normal prior for mu.\nThe dashed vertical line is our 'mean_y' value.")

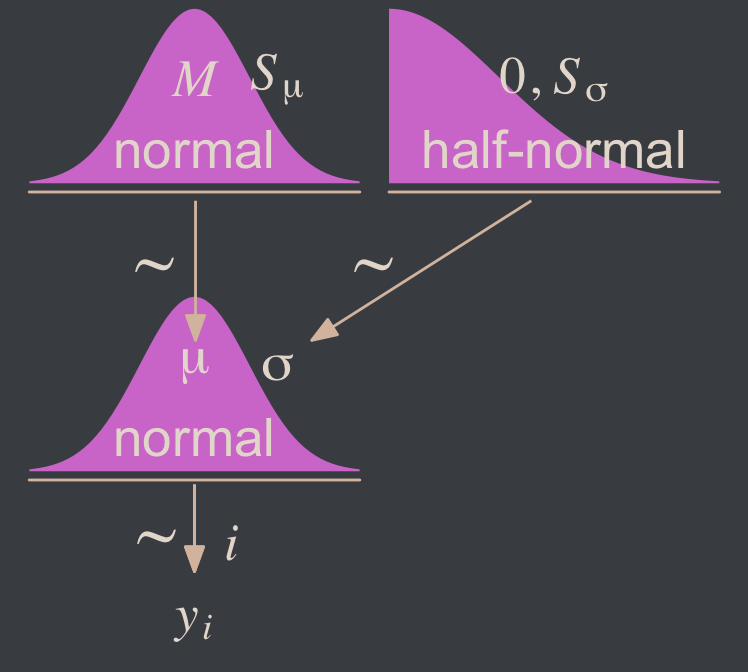

Yep, Kruschke’s right. That is one noncommittal prior given our data. We could tighten that up by an order of magnitude and still have little influence on the posterior. Now we’ve decided on our parameterization (with \(\sigma\), not \(\tau\)) and our priors (half-normal, not uniform or gamma), we are ready to make our version of the model diagram in Figure 16.2.

# Normal density

p1 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = bp[6]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = bp[5], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.5), y = 0.6,

label = c("italic(M)", "italic(S)[mu]"),

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = bp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Half-normal density

p2 <- tibble(x = seq(from = 0, to = 3, by = 0.01),

d = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x))) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d)) +

geom_area(fill = bp[6]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.2,

label = "half-normal",

color = bp[5], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.6,

label = "0*','*~italic(S)[sigma]",

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = bp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

## Two annotated arrows

# Save our custom arrow settings

my_arrow <- arrow(angle = 20, length = unit(0.35, "cm"), type = "closed")

p3 <- tibble(x = c(0.43, 1.5),

y = c(1, 1),

xend = c(0.43, 0.8),

yend = c(0.2, 0.2)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, xend = xend,

y = y, yend = yend)) +

geom_segment(arrow = my_arrow, color = bp[4]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0.3, 1), y = 0.6,

label = "'~'",

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 10) +

xlim(0, 2) +

theme_void()

# A second normal density

p4 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = bp[6]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = bp[5], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.5), y = 0.6,

label = c("mu", "sigma"),

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = bp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# The final annotated arrow

p5 <- tibble(x = c(0.375, 0.625),

y = c(1/3, 1/3),

label = c("'~'", "italic(i)")) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = c(10, 7)) +

geom_segment(x = 0.5, xend = 0.5,

y = 1, yend = 0,

arrow = my_arrow, color = bp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Some text

p6 <- tibble(x = 0.5,

y = 0.5,

label = "italic(y[i])") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Define the layout

layout <- c(

area(t = 1, b = 2, l = 1, r = 2),

area(t = 1, b = 2, l = 3, r = 4),

area(t = 4, b = 5, l = 1, r = 2),

area(t = 3, b = 4, l = 1, r = 4),

area(t = 6, b = 6, l = 1, r = 2),

area(t = 7, b = 7, l = 1, r = 2))

# Combine and plot!

(p1 + p2 + p4 + p3 + p5 + p6) +

plot_layout(design = layout) &

ylim(0, 1) &

theme(plot.margin = margin(0, 5.5, 0, 5.5))

Two things about the notation in our diagram: Because we have two \(\sigma\) hyperparameters, we’ve denoted the one for the prior on \(\mu\) as \(S_\mu\) and the one for the prior on \(\sigma\) as \(S_\sigma\). Also, note that we fixed the \(\mu\) hyperparameter for half-normal prior to zero. This won’t always be the case, but it’s so common within the brms ecosystem that I’m going to express it this way throughout most of this ebook. This is our default.

Here’s how to put these priors to use with brms.

fit16.1 <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = gaussian,

Score ~ 1,

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 100), class = Intercept),

prior(normal(0, sd_y), class = sigma)),

chains = 4, cores = 4,

stanvars = stanvars,

seed = 16,

file = "fits/fit16.01")To be more explicit, the stanvars = stanvars argument at the bottom of our code is what allowed us to define our intercept prior as normal(mean_y, sd_y * 100) instead of requiring us to type in the parameters as normal(107.8413, 25.4452 * 100). The same basic point goes for our \(\sigma\) prior.

Also, notice our prior code for \(\sigma\), prior(normal(0, sd_y), class = sigma). Nowhere in there did we actually say we wanted a half normal as opposed to a typical normal. That’s because the brms default is to set the lower bound for priors of class = sigma to zero. There’s no need for us to fiddle with it.

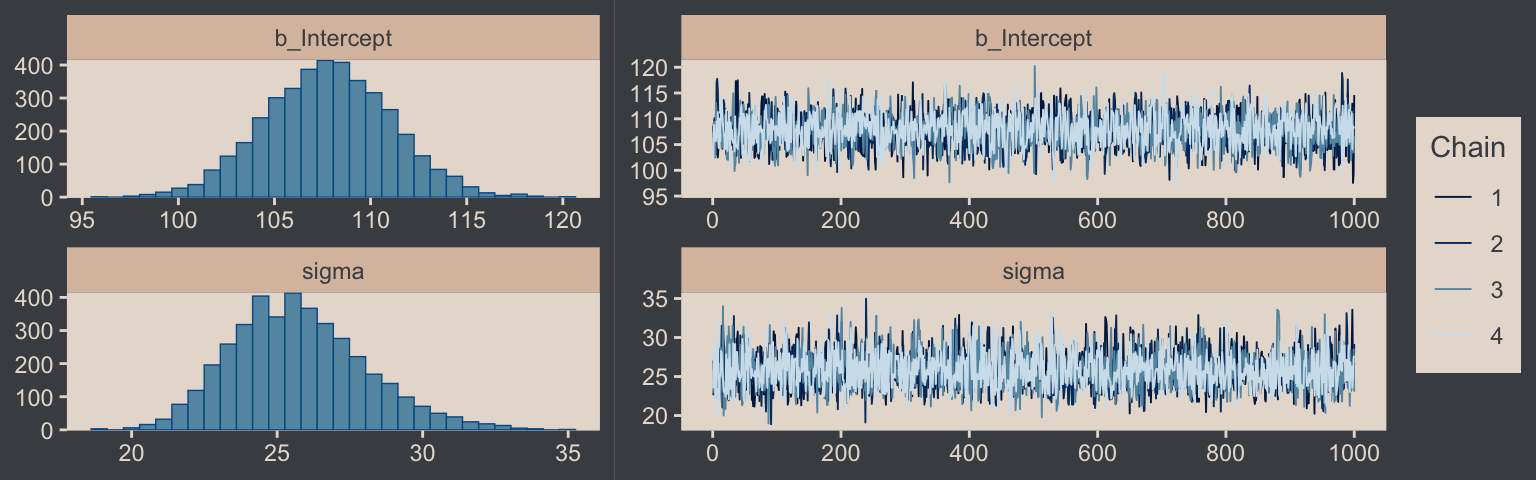

Let’s examine the chains.

plot(fit16.1, widths = 2:3)

They look good! The model summary looks sensible, too.

print(fit16.1) Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity

Formula: Score ~ 1

Data: my_data (Number of observations: 63)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 107.79 3.28 101.46 114.27 1.00 3071 2712

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 25.74 2.31 21.75 30.89 1.00 3636 2673

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Compare those values with mean_y and sd_y.

mean_y[1] 107.8413sd_y[1] 25.4452Good times. Let’s extract the posterior draws and save them in a data frame draws.

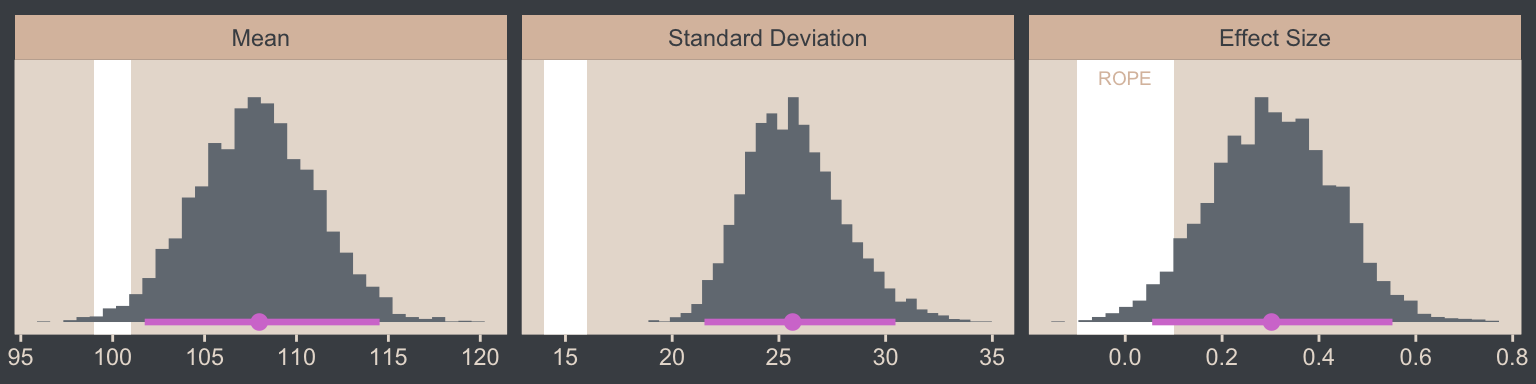

draws <- as_draws_df(fit16.1)Here’s the leg work required to make our version of the three histograms in Figure 16.3.

# To streamline the code

name_levels <- c("mean", "sd", "es")

name_labels <- c("Mean", "Standard Deviation", "Effect Size")

# We'll use this to mark off the ROPEs as white strips in the background

rope <- tibble(name = factor(name_levels, levels = name_levels, labels = name_labels),

xmin = c(99, 14, -0.1),

xmax = c(101, 16, 0.1))

# Annotate the ROPE

d_text <- tibble(x = 0,

y = 0.98,

label = "ROPE",

name = factor("es", levels = name_levels, labels = name_labels))

# Here are the primary data

draws |>

transmute(mean = b_Intercept,

sd = sigma) |>

mutate(es = (mean - 100) / sd) |>

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) |>

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = name_levels, labels = name_labels)) |>

# The plot

ggplot() +

geom_rect(data = rope,

aes(xmin = xmin, xmax = xmax,

ymin = -Inf, ymax = Inf),

color = "transparent", fill = "white") +

stat_histinterval(aes(x = value),

point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = bp[6], fill = bp[2], normalize = "panels") +

geom_text(data = d_text,

aes(x = x, y = y, label = label),

color = bp[4], size = 2.5) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab(NULL) +

facet_wrap(~ name, ncol = 3, scales = "free")

If we wanted those exact modes and 95% HDIs, we might execute this.

draws |>

transmute(mean = b_Intercept,

sd = sigma) |>

mutate(es = (mean - 100) / sd) |>

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) |>

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = name_levels, labels = name_labels)) |>

group_by(name) |>

mode_hdi(value)# A tibble: 3 × 7

name value .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 Mean 108. 102. 115. 0.95 mode hdi

2 Standard Deviation 25.6 21.5 30.5 0.95 mode hdi

3 Effect Size 0.302 0.0556 0.552 0.95 mode hdi For the next part, we should look at the structure of the posterior draws, draws.

head(draws)# A draws_df: 6 iterations, 1 chains, and 5 variables

b_Intercept sigma Intercept lprior lp__

1 107 27 107 -13 -303

2 110 26 110 -13 -302

3 110 25 110 -13 -303

4 106 25 106 -13 -303

5 109 22 109 -13 -303

6 107 29 107 -13 -303

# ... hidden reserved variables {'.chain', '.iteration', '.draw'}By default, head() returned six rows, each one corresponding to the credible parameter values from a given posterior draw. Following our model equation \(\text{Score}_i \sim N(\mu, \sigma)\), we might reformat the first two columns as:

Score~ \(N\)(107.482, 27.046)Score~ \(N\)(109.533, 25.628)Score~ \(N\)(110.115, 25.046)Score~ \(N\)(105.739, 24.913)Score~ \(N\)(108.667, 22.231)Score~ \(N\)(106.599, 28.803)

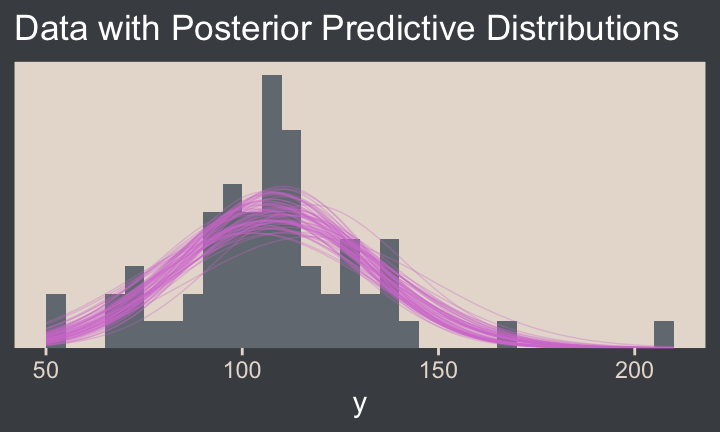

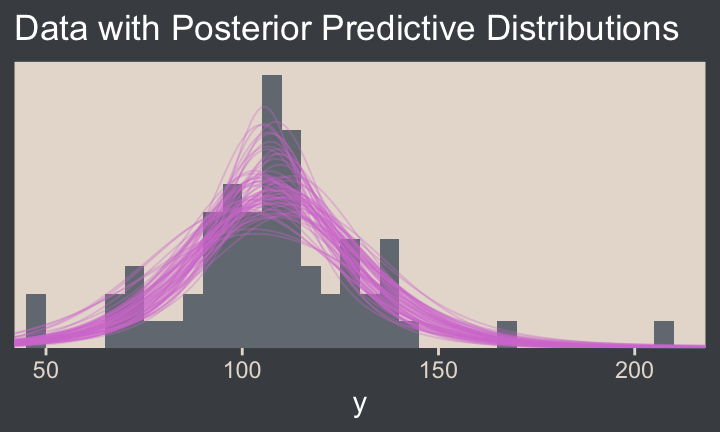

Each row of draws yields a full model equation with which we might credibly describe the data–or at least as credibly as we can within the limits of the model. We can give voice to a subset of these credible distributions with our version of the upper right panel of Figure 16.3.

Before I show that plotting code, it might make sense to slow down on the preparatory data wrangling steps. There are several ways to overlay multiple posterior predictive density lines like those in our upcoming plots. We’ll practice a few over the next few chapters. For the method we’ll use in this chapter, it’s handy to first determine how many you’d like. Here we’ll follow Kruschke and choose 63, which we’ll save as n_lines.

# How many credible density lines would you like?

n_lines <- 63Now we’ve got our n_lines value, we’ll use it to subset the rows in draws with the slice() function. We’ll then subset the columns and use expand_grid() to include a sequence of Score values to correspond to the formula implied in each of the remaining rows of draws. Notice how we also kept the .draw index column. That will help us with the plot in a bit. But the main event is how we used Score, b_Intercept, and sigma as the input for the arguments in the dnorm(). The output is a column of the corresponding density values.

long_draws <- draws |>

slice(1:n_lines) |>

select(.draw, b_Intercept, sigma) |>

expand_grid(Score = seq(from = 40, to = 250, by = 1)) |>

mutate(density = dnorm(x = Score, mean = b_Intercept, sd = sigma))

glimpse(long_draws)Rows: 13,293

Columns: 5

$ .draw <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, …

$ b_Intercept <dbl> 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819, 107.4819…

$ sigma <dbl> 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619, 27.04619…

$ Score <dbl> 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, …

$ density <dbl> 0.0006561302, 0.0007190476, 0.0007869218, 0.0008600264, 0.0009386383, 0.0010230364, 0.0011134999, 0.00121030…We have a rather long data frame after using expand_grid(). We’re ready to plot.

long_draws |>

ggplot(aes(x = Score)) +

geom_histogram(data = my_data,

aes(y = after_stat(density)),

binwidth = 5, boundary = 0,

fill = bp[2], linewidth = 0.2) +

geom_line(aes(y = density, group = .draw),

alpha = 1/3, color = bp[6], linewidth = 1/4) +

scale_x_continuous("y", limits = c(50, 210)) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL, expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

ggtitle("Data with Posterior Predictive Distributions")

Note the after_stat(density) argument in the geom_histogram() function. That’s what rescaled the histogram to the density metric. If you leave that part out, all the density lines will drop to the bottom of the y axis. Also, did you see how we used .draw to group the density lines within the geom_line() function? That’s why we kept that information. Without that group = .draw argument, the resulting lines are a mess.

Kruschke pointed out this last plot

constitutes a form of posterior-predictive check, by which we check whether the model appears to be a reasonable description of the data. With such a small amount of data, it is difficult to visually assess whether normality is badly violated, but there appears to be a hint that the normal model is straining to accommodate some outliers: The peak of the data protrudes prominently above the normal curves, and there are gaps under the shoulders of the normal curves. (p. 458)

We can perform a similar posterior-predictive check with the brms::pp_check() function. By default, it will return 10 simulated density lines. Like we did above, we’ll increase that by setting the ndraws argument to our n_lines value.

color_scheme_set(scheme = bp[c(3, 1, 2, 5, 4, 6)])

pp_check(fit16.1, ndraws = n_lines)

In principle, we didn’t need to load the bayesplot package to use the brms::pp_check() function. But doing so gave us access to the bayesplot::color_scheme_set() function, which allowed us to apply the colors from our color palette to the plot.

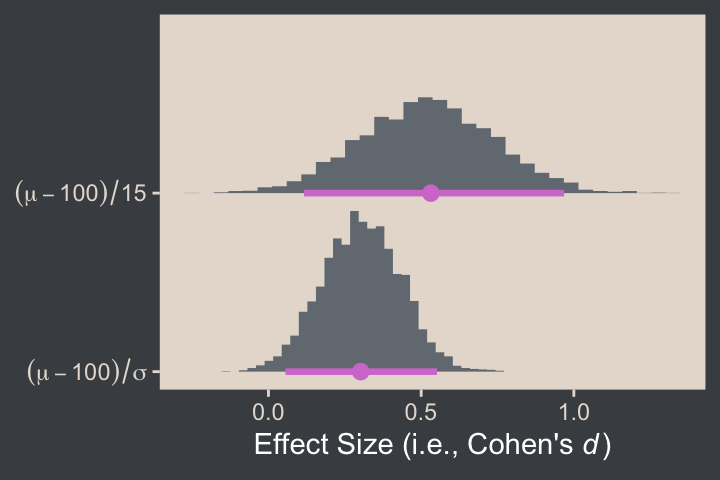

Before we move on, we should talk a little about effect sizes, which we all but glossed over in our code.

Effect size is simply the amount of change induced by the treatment relative to the standard deviation: \((\mu - 100) / \sigma\). In other words, the effect size is the “standardized” change… A conventionally “small” effect size in psychological research is \(0.2\) (Cohen, 1988), and the ROPE limits are set at half that size for purposed of illustration. (p. 457, emphasis in the original).

With all due respect to Kruschke, this is not a good definition for the term effect size. Effect sizes constitute a much broader class of statistical expressions than what Kruschke described in the text. This specific kind of effect size is a form of a Cohen’s \(d\) statistic, Cohen’s \(d\) is itself a class of standardized mean differences (SMDs), and SMDs are themselves only a subset of many many more kinds of effect sizes. In addition to the seminal work by Cohen, I recommend Kelley and Preacher’s (2012) On effect size. I’ll also have a lot more to say about effect sizes in the bonus section, Section 16.5.2

2 Cohen’s \(d\)s are very important to my subdiscipline of clinical psychology, and I’m extra sensitive about this topic.

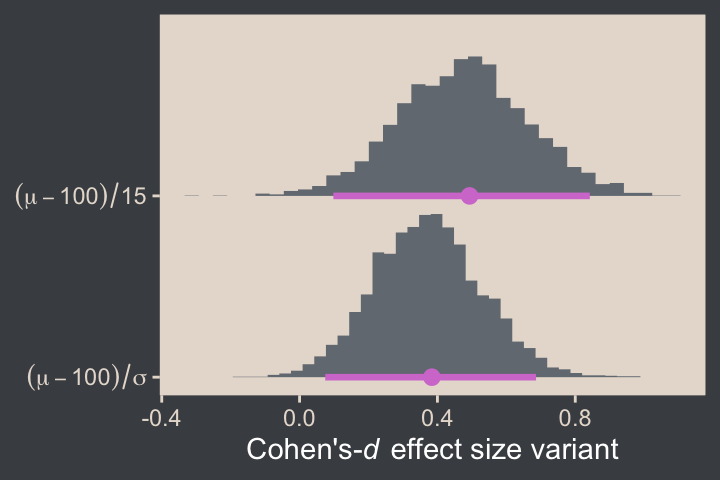

As to the specific effect size \((\mu - 100) / \sigma\), those not familiar with IQ tests should understand that popular IQ tests like the WAIS and WJ are specifically designed to have an overall population mean of 100, and standard deviation of 15. When Kruschke defined his SMD effect size with \(\mu - 100\) in the numerator of the formula, he was comparing the population mean of the data to the overall population mean of the test. It isn’t often the case that one has a known population mean for such a comparison, but it’s very handy when one does. Also note that in this case, Kruschke decided to use the population estimate from the sample \(\sigma\) in the denominator. Another option, and arguably a better one, would have been to use the known population value of 15 instead. Here’s what that would look like compared to the effect size above.

name_labels <- c("(mu-100)/sigma", "(mu-100)/15")

draws |>

transmute(mean = b_Intercept,

sd = sigma) |>

mutate(es_1 = (mean - 100) / sd,

es_2 = (mean - 100) / 15) |>

pivot_longer(cols = es_1:es_2) |>

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = str_c("es_", 1:2), labels = name_labels)) |>

# The plot

ggplot(aes(x = value, y = name)) +

stat_histinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = bp[6], fill = bp[2], normalize = "panels") +

scale_y_discrete(NULL, labels = ggplot2:::parse_safe, expand = expansion(mult = 0.1)) +

xlab(expression("Effect Size (i.e., Cohen's "*italic(d)*")"))

When one computes an SMD effect size, the choice of standardizer matters. Generally, one chooses a standardizer based on disciplinary norms, theoretical considerations, and any other factors that might effect how well a given target audience will understand the information. Science is difficult, statistics are difficult, and it turns out science communication is difficult, too.

16.2 Outliers and robust estimation: The \(t\) distribution

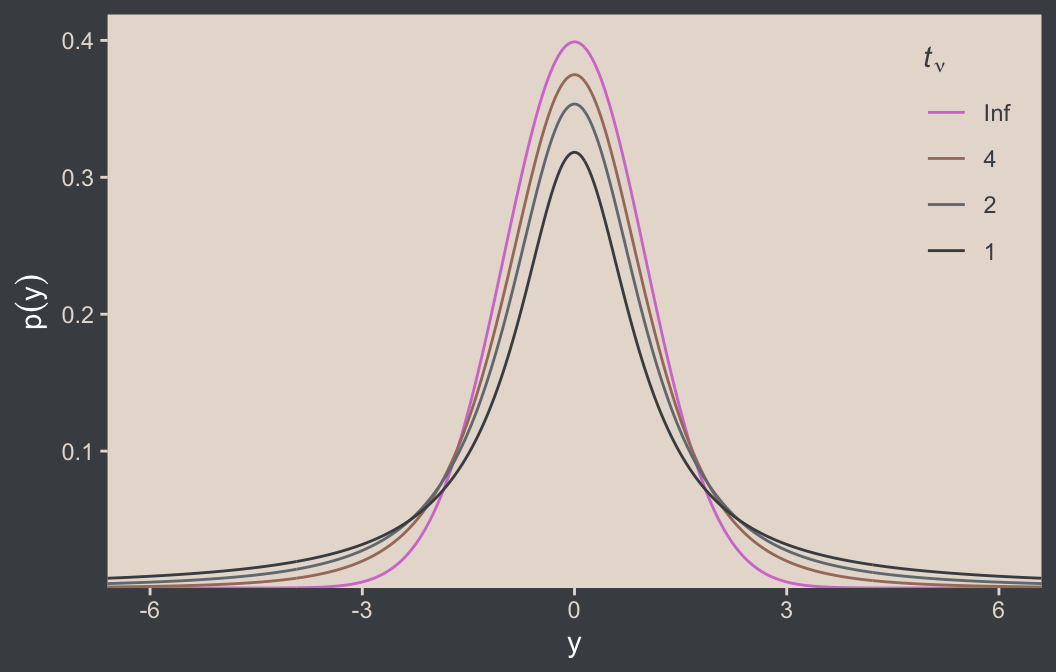

Here’s the code for our version of Figure 16.4, where we visualize several versions of the \(t\) distribution.

# Wrangle

crossing(nu = c(Inf, 4, 2, 1),

y = seq(from = -8, to = 8, length.out = 500)) |>

mutate(density = dt(x = y, df = nu)) |>

# This line is unnecessary, but will help with the plot legend

mutate(nu = factor(nu, levels = c("Inf", "4", "2", "1"))) |>

# Plot

ggplot(aes(x = y, y = density, group = nu, color = nu)) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous(expression(p(y)), expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

scale_color_manual(expression(paste(italic(t)[nu])), values = bp[c(6, 3:1)]) +

guides(colour = guide_legend(position = "inside")) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-6, 6)) +

theme(legend.position.inside = c(0.92, 0.75))

Although the \(t\) distribution is usually conceived as a sampling distribution for the NHST \(t\) test, we will use it instead as a convenient descriptive model of data with outliers… Outliers are simply data values that fall unusually far from a model’s expected value. Real data often contain outliers relative to a normal distribution. Sometimes the anomalous values can be attributed to extraneous influences that can be explicitly identified, in which case the affected data values can be corrected or removed. But usually we have no way of knowing whether a suspected outlying value was caused by an extraneous influence, or is a genuine representation of the target being measured. Instead of deleting suspected outliers from the data according to some arbitrary criterion, we retain all the data but use a noise distribution that is less affected by outliers than is the normal distribution. (p. 459)

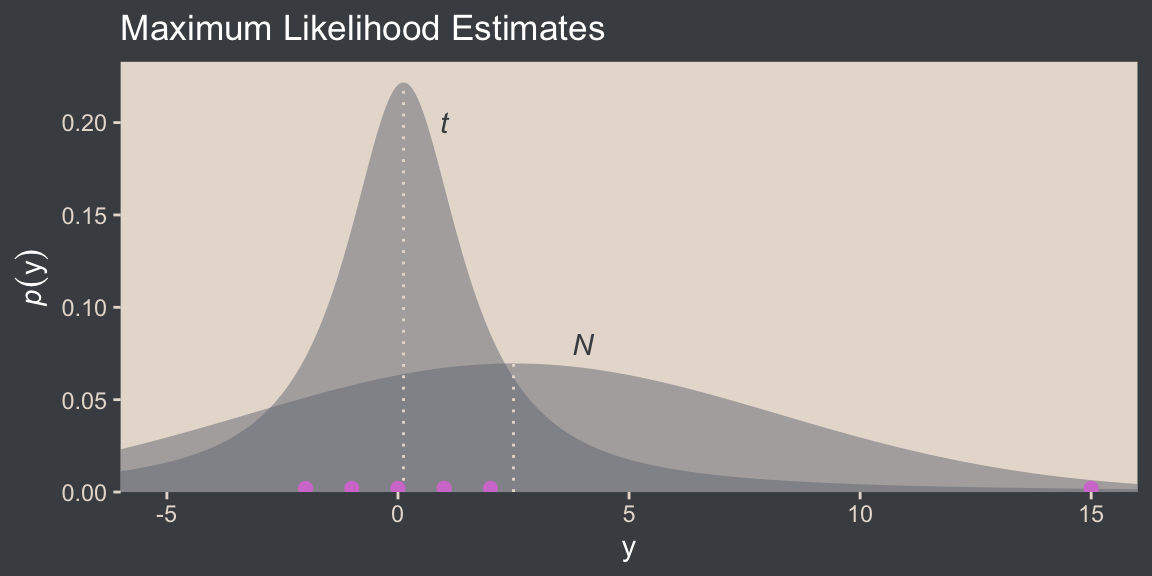

Here’s Figure 16.5.a. Note that since we’d like to work with the \(t\) distribution, we specified dstudent_t() function in one of the geom_area() lines. The dstudent_t() function is from brms, and it gives us access to the scaled \(t\) distribution. Base functions such as dt() use the \(t\) distribution for which the location \(\mu\) is fixed to zero and the scale \(\tau\) is fixed to 1, making it the \(t\)-distribution version of the standardized normal distribution. To go beyond those defaults, we need a scaled and/or shifted \(t\) distribution. For more information, execute ?dstudent_t.

tibble(y = seq(from = -10, to = 20, length.out = 501)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = y)) +

geom_area(aes(y = dnorm(y, mean = 2.5, sd = 5.73)),

alpha = 1/2, fill = bp[2]) +

geom_area(aes(y = dstudent_t(y, df = 1.14, mu = 0.12, sigma = 1.47)),

alpha = 1/2, fill = bp[2]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = c(0.12, 2.5), color = bp[5], linetype = 3) +

annotate(geom = "point",

x = c(-2:2, 15), y = 0.002,

color = bp[6], size = 2) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(1, 4), y = c(0.2, 0.08),

label = c("italic(t)", "italic(N)"),

color = bp[1], parse = TRUE) +

scale_y_continuous(expression(italic(p)(y)), expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

ggtitle("Maximum Likelihood Estimates") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-5, 15))

I do not believe the data for Figure 16.5 are available directly from Kruschke’s supplemental files for the text. However, the caption from the figure indicates they were from Holcomb & Spalsbury (2005). The data can be downloaded directly from https://jse.amstat.org/datasets/calcium.dat.txt, and you can find additional documentation from this link (just use the search term “Holcomb”).

# Define the column names

col_names <- c("obsno", "age", "sex", "alkphos", "lab", "cammol", "phosmmol", "age_group")

# Extract the data from online

d <- read_table(

# The url was working for direct download on April 12, 2025

file = url("https://jse.amstat.org/datasets/calcium.dat.txt"),

col_names = col_names) |>

# Save these variables as factors

mutate(sex = factor(sex, levels = 1:2, labels = c("male", "female")),

lab = factor(lab, levels = 1:6, labels = c("Metpath", "Deyor", "St. Elizabeth's", "CB Rouche", "YOH", "Horizon")),

age_group = factor(age_group, levels = 1:5, labels = c("65-69", "70-74", "75-79", "80-84", "85-89")))

glimpse(d)Rows: 178

Columns: 8

$ obsno <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30,…

$ age <dbl> 78, 72, 72, 73, 73, 73, 65, 68, 89, 84, 771, 80, 80, 76, 70, 70, 71, 70, 70, 66, 76, 76, 68, 69, 76, 70, 71, 7…

$ sex <fct> female, female, female, female, female, female, female, female, male, male, male, female, female, female, fema…

$ alkphos <dbl> 83, 117, 132, 102, 114, 88, 213, 153, 86, 108, 96, 58, 45, 73, 91, 57, 159, 52, 67, 111, 84, 5, 82, 84, 100, 9…

$ lab <fct> CB Rouche, CB Rouche, CB Rouche, CB Rouche, CB Rouche, NA, CB Rouche, CB Rouche, CB Rouche, CB Rouche, CB Rouc…

$ cammol <dbl> 2.53, 2.50, 2.43, 2.48, 2.33, 2.13, 2.55, 2.45, 2.25, 2.43, 2.40, 2.25, 2.18, 2.55, 2.38, 2.30, 2.60, 2.20, 2.…

$ phosmmol <dbl> 1.07, 1.16, 1.13, 0.81, 1.13, 0.84, 1.26, 1.23, 0.65, 0.84, 1.10, 1.10, 1.49, 1.23, 1.42, 1.16, 1.32, 1.07, 1.…

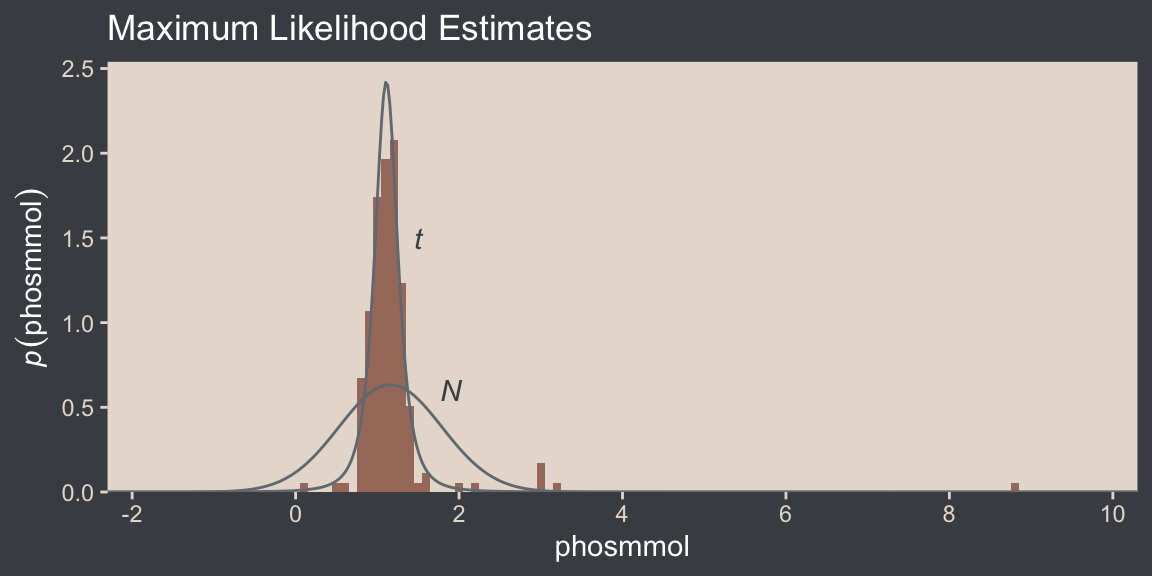

$ age_group <fct> 75-79, 70-74, 70-74, 70-74, 70-74, 70-74, 65-69, 65-69, 85-89, 80-84, 70-74, 80-84, 80-84, 75-79, 70-74, 70-74…For the figure, our focal variable will be phosmmol

d |>

drop_na(phosmmol) |>

ggplot(aes(x = phosmmol)) +

geom_histogram(aes(y = after_stat(density)),

binwidth = 0.1, fill = bp[3], linewidth = 0.2) +

stat_function(fun = dnorm, args = list(mean = 1.16, sd = 0.63),

color = bp[2], n = 501, xlim = c(-2.3, 10.3)) +

stat_function(fun = dstudent_t, args = list(df = 2.63, mu = 1.11, sigma = 0.15),

color = bp[2], n = 501, xlim = c(-2.3, 10.3)) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(1.5, 1.9), y = c(1.5, 0.6),

label = c("italic(t)", "italic(N)"),

color = bp[1], parse = TRUE) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = -1:5 * 2, expand = expansion(mult = 0)) +

scale_y_continuous(expression(italic(p)(phosmmol)), expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

ggtitle("Maximum Likelihood Estimates")

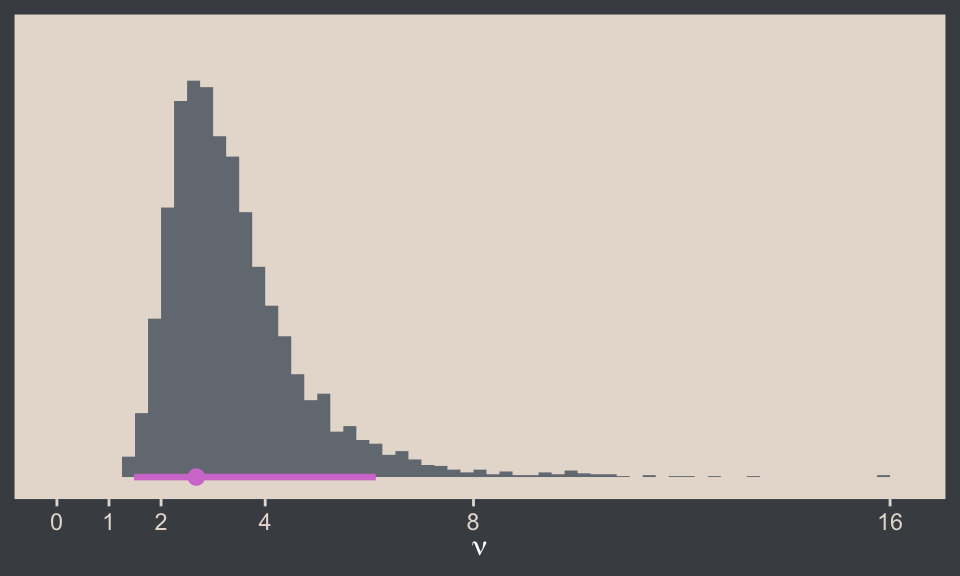

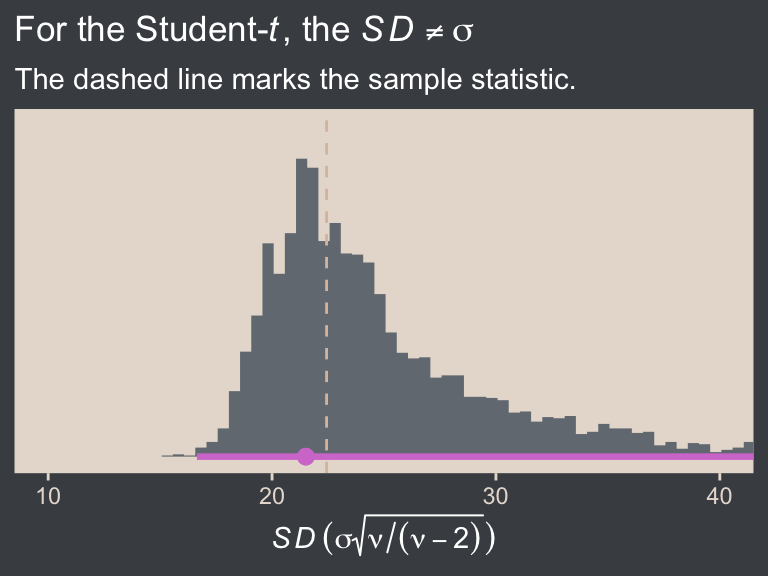

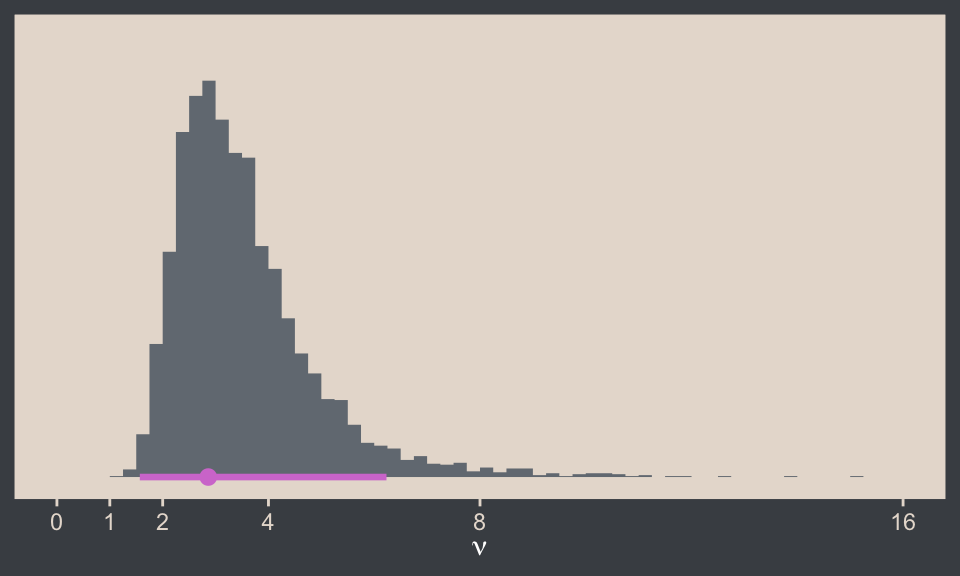

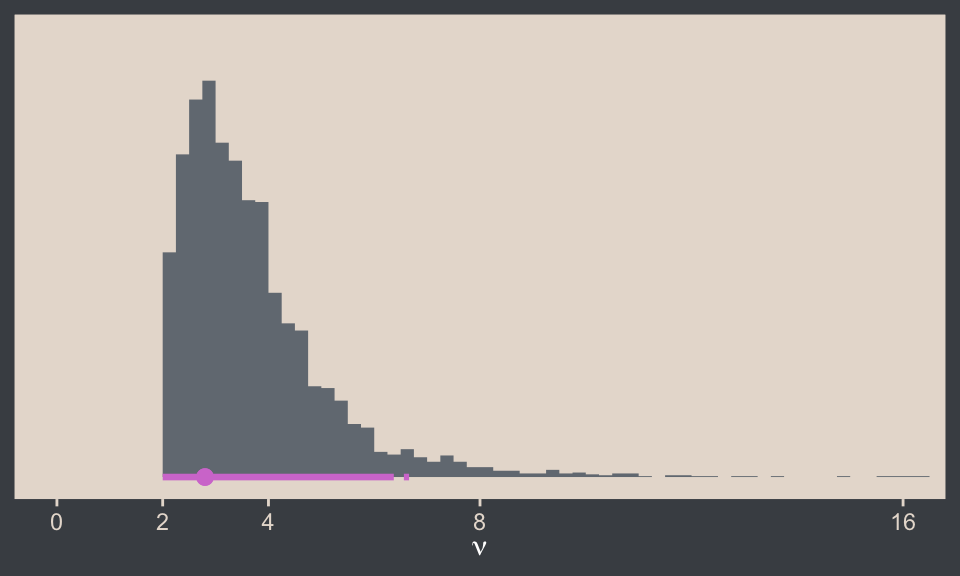

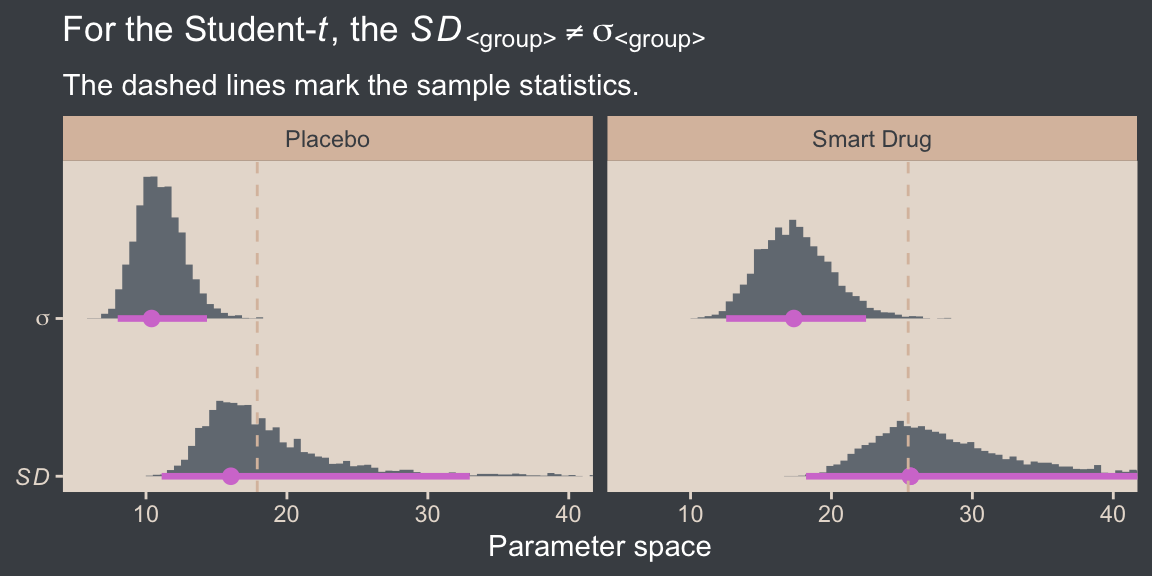

We learn more details about the Student-\(t\) scale parameter \(\sigma\) and its relation to the standard deviation:

It is important to understand that the scale parameter \(\sigma\) in the \(t\) distribution is not the standard deviation of the distribution. (Recall that the standard deviation is the square root of the variance, which is the expected value of the squared deviation from the mean, as defined back in Equation 4.8, p. 86.) The standard deviation is actually larger than \(\sigma\) because of the heavy tails… While this value of the scale parameter is not the standard deviation of the distribution, it does have an intuitive relation to the spread of the data. Just as the range \(\pm \sigma\) covers the middle \(68\%\) of a normal distribution, the range \(\pm \sigma\) covers the middle \(58\%\) of a \(t\) distribution when \(\nu = 2\), and the middle \(50\%\) when \(\nu = 1\). These areas are illustrated in the left column of Figure 16.6. The right column of Figure 16.6 shows the width under the middle of a \(t\) distribution that is needed to span \(68.27\%\) of the distribution, which is the area under a normal distribution for \(\sigma = \pm 1\). (pp. 459–461, emphasis in the original)

For example, in the lower panel of Kruschke’s Figure 16.5, \(\nu = 2.63\) and \(\sigma = 0.15\). Because \(\nu > 2\), the standard deviation is defined and finite, and we can compute the standard deviation like so:

# Figure 16.5 (lower panel)

nu <- 2.63

sigma <- 0.15

sigma * sqrt(nu / (nu - 2))[1] 0.3064777But because \(\nu = 1.14\) for the upper panel in Kruschke’s Figure 16.5, we run into trouble.

# Figure 16.5 (upper panel)

nu <- 1.14

sigma <- 1.47

sigma * sqrt(nu / (nu - 2))Warning in sqrt(nu/(nu - 2)): NaNs produced[1] NaNThe trouble arises from the sqrt(nu / (nu - 2)) portion of the computation. Because nu / (nu - 2) returns a negative value (-1.3), we end up with an imaginary number, which isn’t great from a computational standpoint. But anyways, for \(t\) distributions for which \(\nu > 2\), the standard deviation follows the formula

\[\textit{SD} = \sigma \sqrt{\nu / (\nu - 2)}.\]

This will all become important later. For now, here’s the code for the left column for Figure 16.6.

# Save a vector

nu <- c(Inf, 5, 2, 1)

# The primary data

d <- crossing(y = seq(from = -8, to = 8, length.out = 1e3),

nu = nu) |>

mutate(density = dt(y, df = nu),

strip = fct_rev(str_c("nu==", nu)))

# For annotation

d_text <- tibble(y = 0,

nu = nu) |>

mutate(p = pt(1, df = nu) - pt(-1, df = nu)) |>

mutate(label = str_c(round(100 * p, digits = 0), "%"),

strip = fct_rev(str_c("nu==", nu)))

# The subplot

p1 <- d |>

ggplot(aes(x = y)) +

geom_area(aes(y = density),

fill = bp[2]) +

geom_area(data = d |> filter(y >= -1 & y <= 1),

aes(y = density),

fill = bp[1]) +

# Note how this function has its own data

geom_text(data = d_text,

aes(y = 0.175, label = label),

color = "white") +

scale_y_continuous(expression(italic(p)(y)), breaks = c(0, 0.2, 0.4),

expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-6, 6)) +

facet_grid(strip ~ "Shaded~from~italic(y)==-1~to~italic(y)==1", labeller = label_parsed) +

theme(strip.text.y = element_blank())Here’s the code for the right column.

# Save a constant for the area under the curve (AUC)

auc <- (pt(1, df = Inf) - pt(-1, df = Inf))

# The primary data

d <- tibble(nu = nu,

ymin = qt((1 - auc) / 2, df = nu)) |>

mutate(ymax = -ymin) |>

expand_grid(y = seq(from = -8, to = 8, length.out = 1e3)) |>

mutate(density = dt(y, df = nu),

strip = fct_rev(str_c("nu==", nu)))

# The subplot

p2 <- d |>

ggplot(aes(x = y)) +

geom_area(aes(y = density),

fill = bp[2]) +

geom_area(data = d |>

# Notice the `filter()` code has changed

filter(y >= ymin & y <= ymax),

aes(y = density),

fill = bp[1]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.175,

label = "68%", color = "white") +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL, expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-6, 6)) +

facet_grid(strip ~ "'Shaded for the middle 68.27%'", labeller = label_parsed)Now we bind the two ggplots together with the patchwork package to make the full version of Figure 16.6.

p1 + p2

The use of a heavy-tailed distribution is often called robust estimation because the estimated value of the central tendency is stable, that is, “robust,” against outliers. The \(t\) distribution is useful as a likelihood function for modeling outliers at the level of observed data. But the \(t\) distribution is also useful for modeling outliers at higher levels in a hierarchical prior. We will encounter several applications. (p. 462, emphasis in the original)

16.2.1 Using the \(t\) distribution in JAGS brms

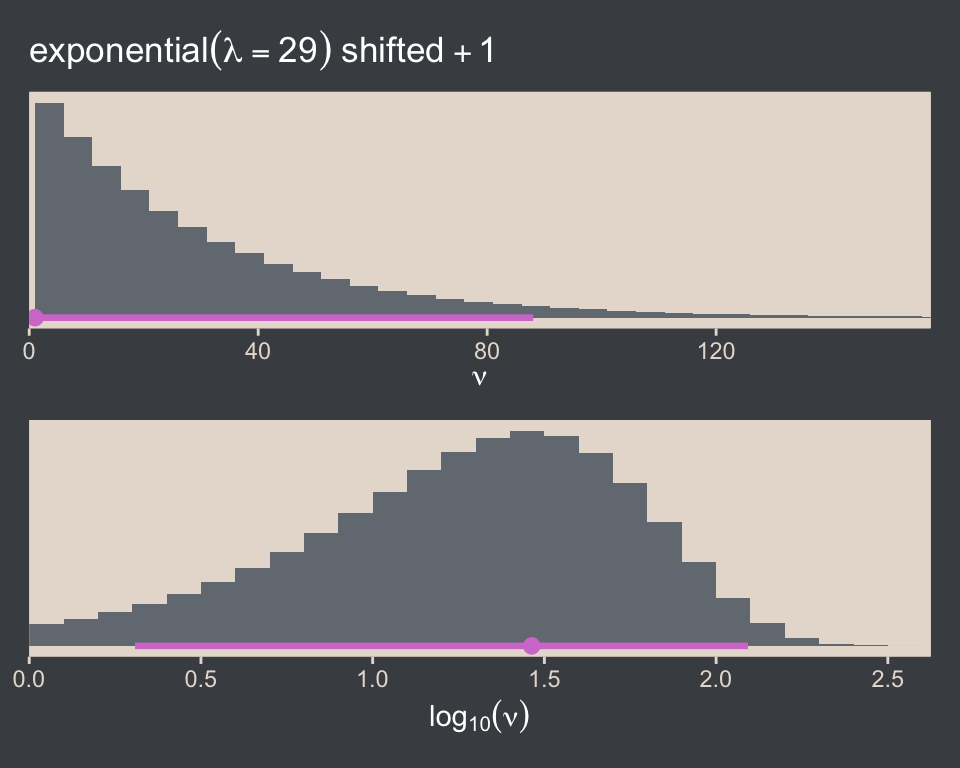

It’s easy to use Student’s \(t\) in brms. Just make sure to set family = student. By default, brms already sets the lower bound for \(\nu\) to 1. But we do still need to use 1/29. To get a sense, let’s simulate exponential data using the rexp() function. Like Kruschke covered in the text (p. 462), the rexp() function has one parameter, rate, which is the reciprocal of the mean. Here we’ll set the mean to 29.

n_draws <- 1e7

mu <- 29

set.seed(16)

tibble(y = rexp(n = n_draws, rate = 1 / mu)) |>

mutate(y_at_least_1 = ifelse(y < 1, NA, y)) |>

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) |>

group_by(name) |>

summarise(mean = mean(value, na.rm = TRUE))# A tibble: 2 × 2

name mean

<chr> <dbl>

1 y 29.0

2 y_at_least_1 30.0The simulation showed that when we define the exponential rate as 1/29 and use the typical boundary at 0, the mean of our samples converges to 29. But when we only consider the samples of 1 or greater, the mean converges to 30. Thus, our \(\operatorname{Exponential}(1/29)\) prior with a boundary at 1 is how we get a shifted exponential distribution when we use it as our prior for \(\nu\) in brms. Just make sure to remember that if you want the mean to be 30, you’ll need to specify the rate of 1/29.

Also, Stan will bark if you simply try to set that exponential prior with the code prior(exponential(1/29), class = nu):

DIAGNOSTIC(S) FROM PARSER: Info: integer division implicitly rounds to integer. Found int division: 1 / 29 Positive values rounded down, negative values rounded up or down in platform-dependent way.

To avoid this, just do the division beforehand and save the results with stanvar().3

3 You will run into similar problems if you try exponential(1.0/29), exponential(1/29.0), or exponential(1.0/29.0). For more on what is even meant by the “integer division” issue, see this section from the Stan Functions Reference. But if you really don’t want to use the stanvar() approach and you’re okay with a little rounding, you can just enter in something like exponential(0.03448276).

stanvars <- stanvar(mean_y, name = "mean_y") +

stanvar(sd_y, name = "sd_y") +

stanvar(1/29, name = "one_over_twentynine")Here’s the brm() code. Note that we set the prior for our new \(\nu\) parameter by specifying class = nu within the last prior() line. Also keep in mind here that whereas Kruschke’s JAGS code parameterized dt() in terms of inverse scale, brms parameterizes the \(t\) distribution in terms of scale, just like it parameterizes the normal distribution in terms of scale.4

4 For the technical details, see this section of Bürkner (2022b) or this section of Stan Development Team (2024).

fit16.2 <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = student,

Score ~ 1,

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 100), class = Intercept),

prior(normal(0, sd_y), class = sigma),

prior(exponential(one_over_twentynine), class = nu)),

chains = 4, cores = 4,

stanvars = stanvars,

seed = 16,

file = "fits/fit16.02")We can make the shifted exponential distribution (i.e., Figure 16.7) with simple addition.

# How many draws would you like?

n_draws <- 1e6

# Here are the data

d <- tibble(exp = rexp(n_draws, rate = 1/29)) |>

transmute(exp_plus_1 = exp + 1,

log_10_exp_plus_1 = log10(exp + 1))

# This is the plot in the top panel

p1 <- d |>

ggplot(aes(x = exp_plus_1)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 5, boundary = 1,

fill = bp[2], linewidth = 0.2, ) +

stat_pointinterval(aes(y = 0),

point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95, color = bp[6]) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

labs(x = expression(nu),

title = expression(exponential(lambda==29)~shifted~+1)) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 150))

# The bottom panel plot

p2 <- d |>

ggplot(aes(x = log_10_exp_plus_1)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.1, boundary = 0,

fill = bp[2], linewidth = 0.2) +

stat_pointinterval(aes(y = 0),

point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95, color = bp[6]) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab(expression(log[10](nu))) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 2.5))

# Combine, adjust, and display

(p1 / p2) & scale_x_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05)))

Kruschke wrote:

It should be emphasized that this choice of prior for \(\nu\) is not uniquely “correct.” While it is well motivated and has reasonable operational characteristics in many applications, there may be situations in which you would want to put more or less prior mass on small values of \(\nu\).

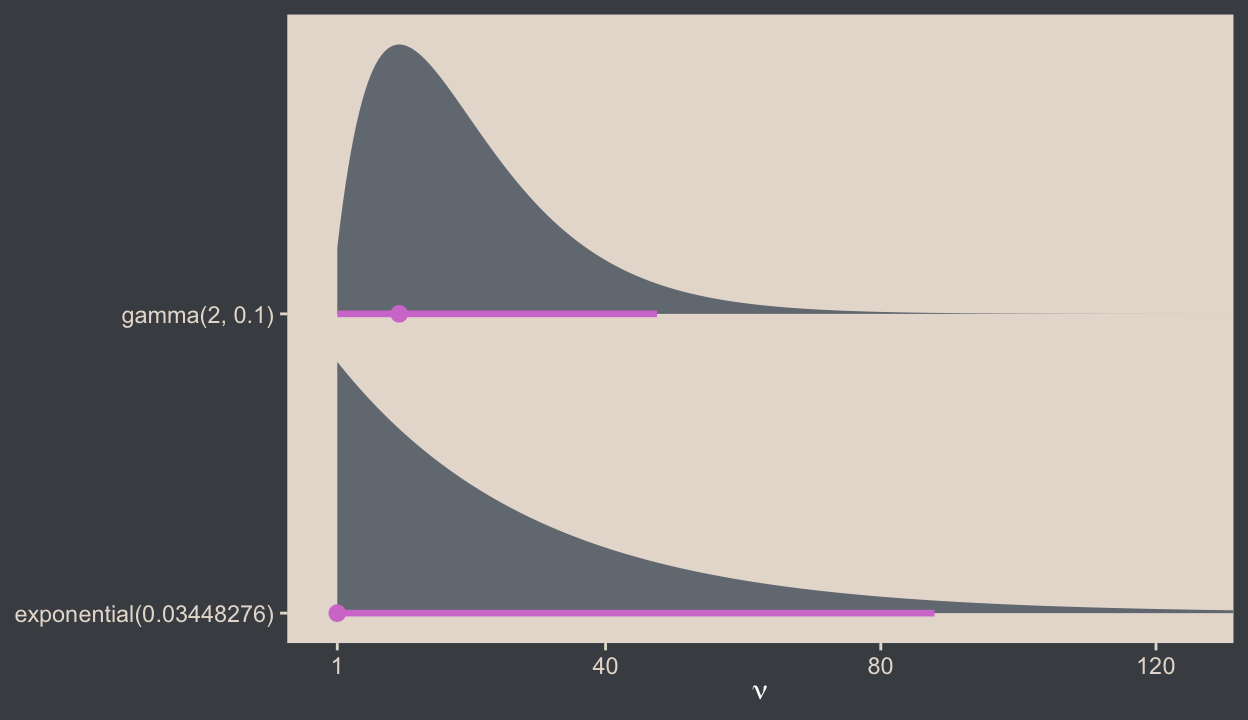

We might use parse_dist() to compare it to the brms default gamma(2, 0.1).

c(prior(gamma(2, 0.1), lb = 1), # brms default

prior(exponential(0.03448276), lb = 1)) |> # 1/29 is about 0.03448276

parse_dist() |>

ggplot(aes(y = prior, dist = .dist_obj)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = bp[6], fill = bp[2]) +

scale_x_continuous(expression(nu), breaks = c(1, 40, 80, 120)) +

scale_y_discrete(NULL, expand = expansion(mult = 0.1)) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 125))

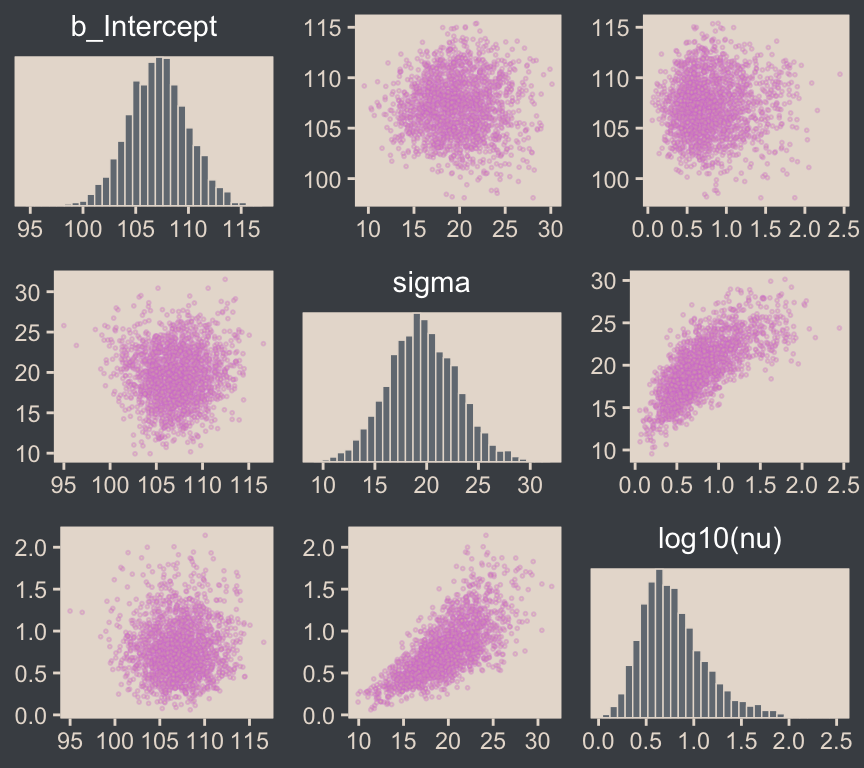

You can get some background on the brms default in the Stan wiki, and we’ll have more to say about \(\nu\) priors a bit. For now, here is a version of the scatter plots of Figure 16.8.

pairs(fit16.2,

off_diag_args = list(alpha = 1/3, size = 1/3),

transformations = list(nu = "log10"))

For brmsfit objects, the pairs() function is a wrapper around the mcmc_pairs() function from the bayesplot package. The transformations argument from mcmc_pairs() allows one to transform one or more parameters with named functions.5

5 Execute ?pairs.brmsfit and ?bayesplot::mcmc_pairs for further documentation.

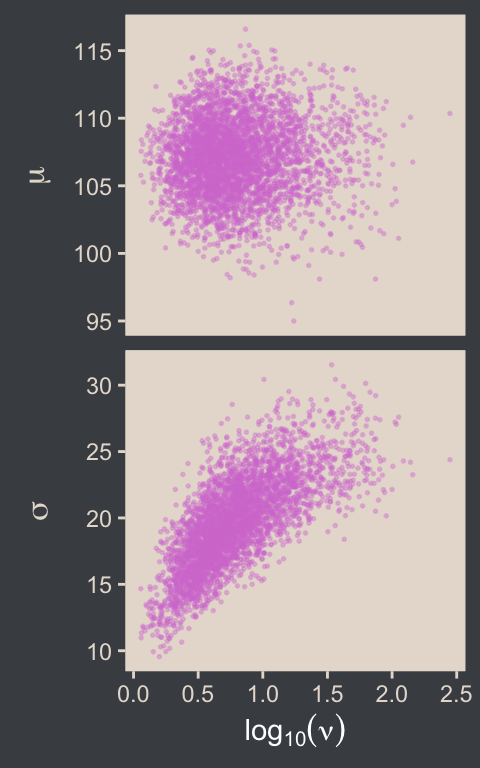

If you want a finer level of control for the plots, you can always start by pulling the posterior draws with as_draws_df() and then making the plot yourself with ggplot2.

draws <- as_draws_df(fit16.2)

draws |>

mutate(`log10(nu)` = log10(nu)) |>

rename(mu = b_Intercept) |>

select(mu, sigma, `log10(nu)`) |>

pivot_longer(cols = -`log10(nu)`) |>

ggplot(aes(x = `log10(nu)`, y = value)) +

geom_point(alpha = 1/3, color = bp[6], size = 1/3) +

labs(x = expression(log[10](nu)),

y = NULL) +

facet_grid(name ~ ., labeller = label_parsed, scales = "free", switch = "y") +

theme(strip.background = element_rect(fill = "transparent"),

strip.placement = "outside",

strip.text = element_text(color = beyonce_palette(126)[5], size = 12))

As we’ll later see in Section 18.1.3, we can make plots even closer to Kruschke’s Figure 16.8 with help from the GGally package. For now, you can use base R cor() function if you want the Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

draws |>

mutate(`log10(nu)` = log10(nu)) |>

select(b_Intercept, sigma, `log10(nu)`) |>

cor() |>

round(digits = 3) b_Intercept sigma log10(nu)

b_Intercept 1.000 0.021 0.033

sigma 0.021 1.000 0.721

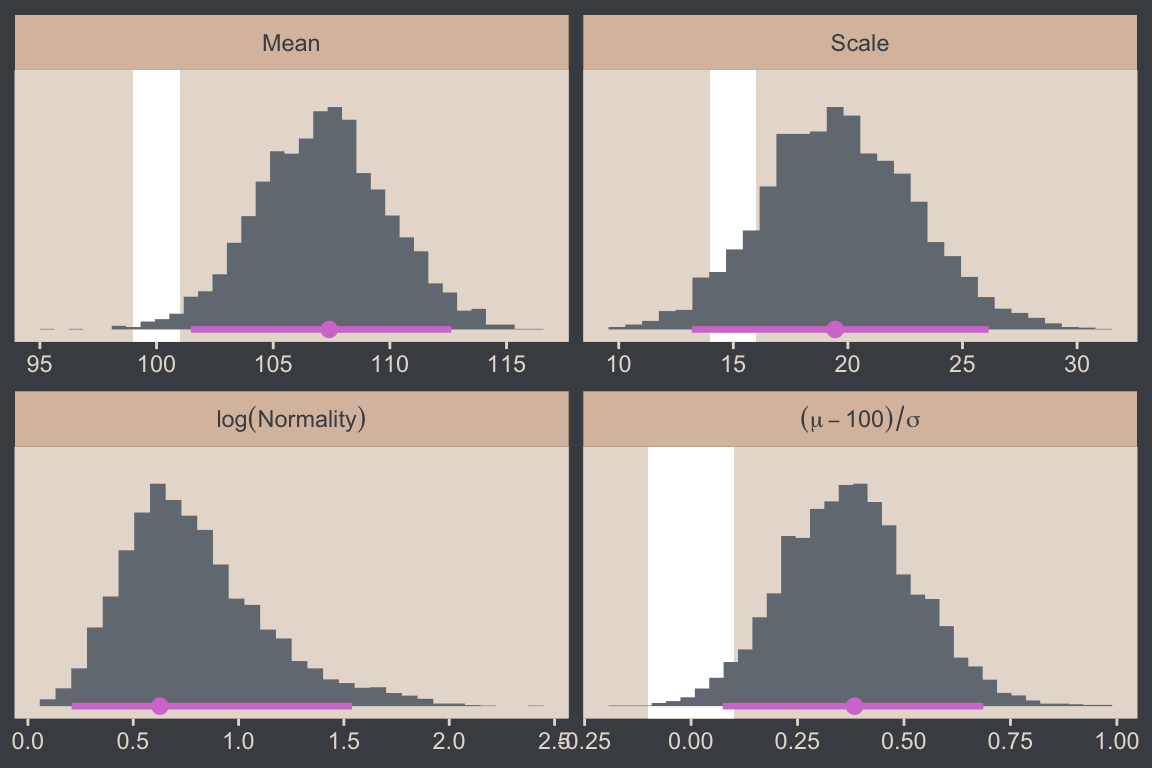

log10(nu) 0.033 0.721 1.000The correlations among our parameters are similar in magnitude to those Kruschke presented in the text. Here are four of the panels for Figure 16.9.

# To streamline the code

name_levels <- c("mean", "scale", "df", "es")

name_labels <- c("Mean", "Scale", "log(Normality)", "(mu-100)/sigma")

# We'll use this to mark off the ROPEs as white strips in the background

rope <- tibble(

name = factor(name_levels[-3], levels = name_levels, labels = name_labels),

xmin = c(99, 14, -0.1),

xmax = c(101, 16, 0.1))

# Here are the primary data

draws |>

transmute(mean = b_Intercept,

scale = sigma,

df = log10(nu)) |>

mutate(es = (mean - 100) / scale) |>

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) |>

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = name_levels, labels = name_labels)) |>

# Plot

ggplot() +

geom_rect(data = rope,

aes(xmin = xmin, xmax = xmax,

ymin = -Inf, ymax = Inf),

color = "transparent", fill = "white") +

stat_histinterval(aes(x = value, y = 0),

point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = bp[6], fill = bp[2],

normalize = "panels") +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab(NULL) +

facet_wrap(~ name, labeller = label_parsed, ncol = 2, scales = "free")

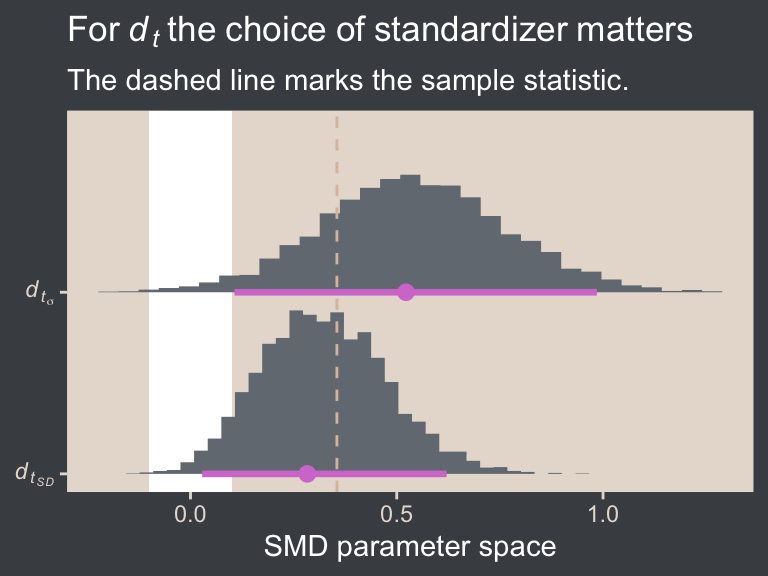

As we discussed toward the end of Section 16.1.2, the language of effect size is a little vague, here. In Kruschke’s version of the figure, he clarified in his x-axis label the formula was \((\mu - 100) / \sigma\), which is a version of Cohen’s \(d\) SMD applied to IQ data. The IQ-data part is important, because we know that 100 is the population mean for IQ test scores, and should not be confused as a part of the equation you’d use in other contexts. Another issue here is when Kruschke used this same formula in the context of the Gaussian model we fit in Section 16.1.2, the \(\sigma\) part was the same as the standard deviation parameter from the model. However, the \(\sigma\) is not the same as the standard deviation in the context of a \(t\) model. Rather, in this case, \(\sigma\) is the scale parameter, and it’s not entirely clear what it would mean to standardize a mean difference with a Student-\(t\) scale. We’ll explore this issue later in Section 16.5. For now, we’ll set the stage by comparing Kruschke’s \((\mu - 100) / \sigma\) with \((\mu - 100) / 15\), where we replace the Student-\(t\) scale parameter with the population standard deviation for IQ test scores: 15.

name_labels <- c("(mu-100)/sigma", "(mu-100)/15")

draws |>

transmute(mean = b_Intercept,

scale = sigma) |>

mutate(es_1 = (mean - 100) / scale,

es_2 = (mean - 100) / 15) |>

pivot_longer(cols = es_1:es_2) |>

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = str_c("es_", 1:2), labels = name_labels)) |>

# The plot

ggplot(aes(x = value, y = name)) +

stat_histinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = bp[6], fill = bp[2], normalize = "panels") +

scale_y_discrete(NULL, labels = ggplot2:::parse_safe, expand = expansion(mult = 0.1)) +

xlab(expression("Cohen's-"*italic(d)*" effect size variant"))

For the final panel of Figure 16.9, we’ll make our \(t\) lines in much the same way we did, earlier. But last time, we just took the first \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) values from the first 63 rows of the post tibble. This time we’ll use dplyr::slice_sample() to take random draws from the post rows instead. We tell slice_sample() how many draws we’d like with the n argument.

In addition to the change in our row selection strategy, this time we’ll slightly amend the code within the last mutate() line. Since we’d like to work with the \(t\) distribution, we specified dstudent_t() function in place of dnorm().

# How many credible density lines would you like?

n_lines <- 63

# Setting the seed makes the results from `slice_sample()` reproducible

set.seed(16)

# Wrangle

draws |>

slice_sample(n = n_lines) |>

expand_grid(Score = seq(from = 40, to = 250, by = 1)) |>

mutate(density = dstudent_t(x = Score, df = nu, mu = b_Intercept, sigma = sigma)) |>

# Plot

ggplot(aes(x = Score)) +

geom_histogram(data = my_data,

aes(y = after_stat(density)),

binwidth = 5, boundary = 0,

fill = bp[2], linewidth = 0.2) +

geom_line(aes(y = density, group = .draw),

alpha = 1/3, color = bp[6], linewidth = 1/3) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL, expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

labs(x = "y",

title = "Data with Posterior Predictive Distributions") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(50, 210))

Much like Kruschke mused in the text, this plot

shows that the posterior predictive \(t\) distributions appear to describe the data better than the normal distribution in Figure 16.3, insofar as the data histogram does not poke out at the mode and the gaps under the shoulders are smaller. (p. 464)

In case you were wondering, here’s the model summary().

summary(fit16.2) Family: student

Links: mu = identity

Formula: Score ~ 1

Data: my_data (Number of observations: 63)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 107.12 2.82 101.53 112.69 1.00 2226 2081

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 19.64 3.33 13.33 26.35 1.00 1912 1785

nu 9.11 12.26 1.84 43.78 1.00 1929 2116

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).It’s easy to miss how

\(\sigma\) in the robust estimate is much smaller than in the normal estimate. What we had interpreted as increased standard deviation induced by the smart drug might be better described as increased outliers. Both of these differences, that is, \(\mu\) more tightly estimated and \(\sigma\) smaller in magnitude, are a result of there being outliers in the data. The only way a normal distribution can accommodate the outliers is to use a large value for \(\sigma\). In turn, that leads to “slop” in the estimate of \(\mu\) because there is a wider range of \(\mu\) values that reasonably fit the data when the standard deviation is large. (p. 464)

We can use the brms::VarCorr() function to pull the summary statistics for \(\sigma\) from both models. For more convenient output, we nest those calls within rbind().

rbind(VarCorr(fit16.1)$residual__$sd, # Gaussian, larger scale

VarCorr(fit16.2)$residual__$sd) # Robust t, smaller scale Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

25.74096 2.308776 21.75037 30.89217

19.64420 3.325958 13.32603 26.34786It is indeed the case that estimate for \(\sigma\) is smaller in the \(t\) model. That smaller \(\sigma\) resulted in a more precise estimate for \(\mu\), as can be seen in the ‘Est.Error’ columns from the fixef() output.

rbind(fixef(fit16.1), # Gaussian, less precise mu

fixef(fit16.2)) # Robust t, more precise mu Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

Intercept 107.7866 3.275494 101.4619 114.2670

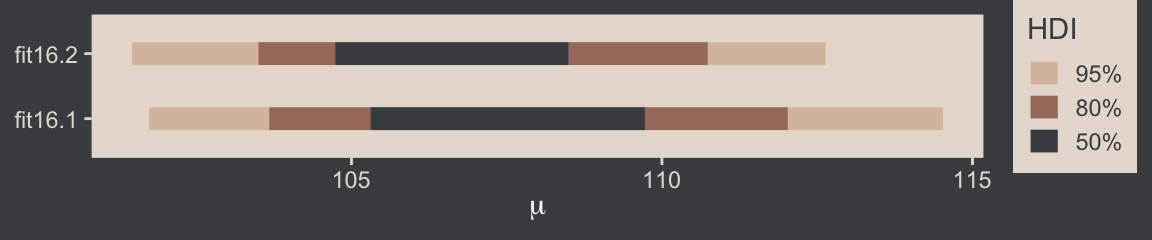

Intercept 107.1201 2.816808 101.5338 112.6862Here that is in a coefficient plot using tidybayes::stat_interval().

bind_rows(as_draws_df(fit16.1), as_draws_df(fit16.2)) |>

select(b_Intercept) |>

mutate(fit = rep(c("fit16.1", "fit16.2"), each = n() / 2)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = b_Intercept, y = fit)) +

stat_interval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = c(0.5, 0.8, 0.95)) +

scale_color_manual("HDI", values = c(bp[c(4, 3, 1)]),

labels = c("95%", "80%", "50%")) +

labs(x = expression(mu),

y = NULL) +

theme(legend.key.size = unit(0.45, "cm"))

16.2.2 Using the \(t\) distribution in Stan

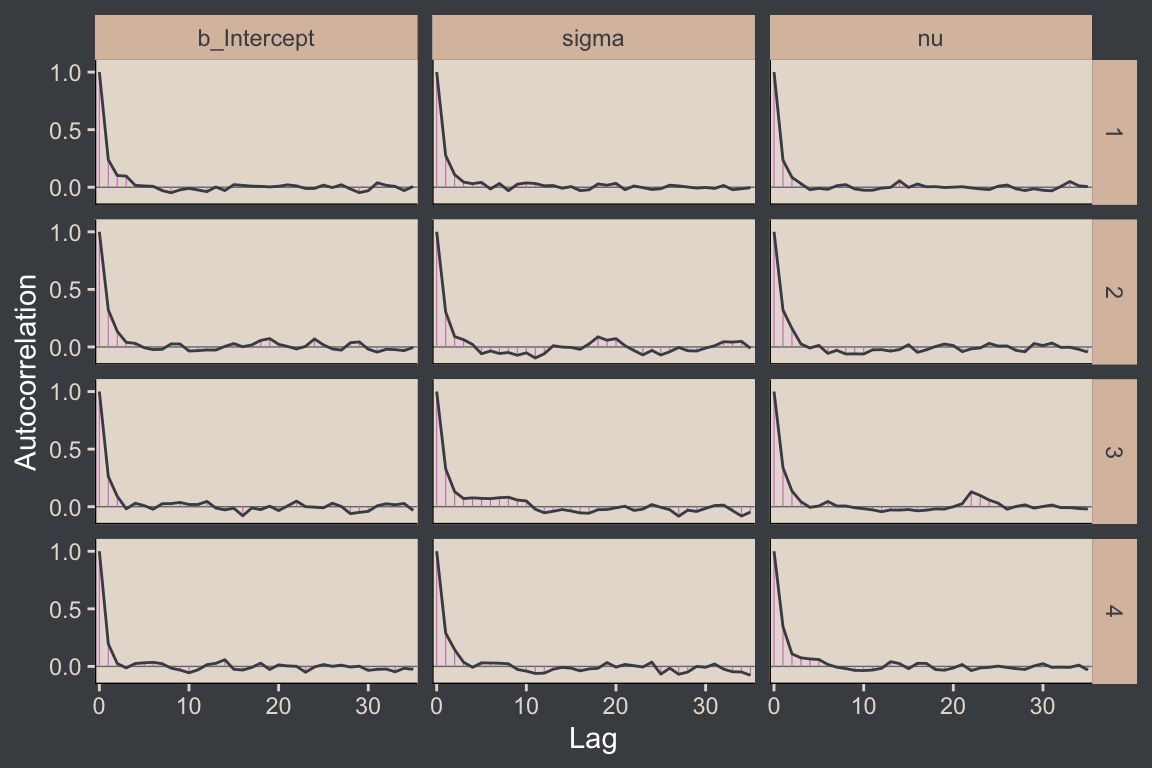

Kruschke expressed concern about high autocorrelations in the chains of his JAGS model. Here are the results of our Stan/brms attempt.

# Rearrange the bayesplot color scheme

color_scheme_set(scheme = bp[c(6, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2)])

draws |>

mutate(chain = .chain) |>

mcmc_acf(pars = vars(b_Intercept:nu), lags = 35)

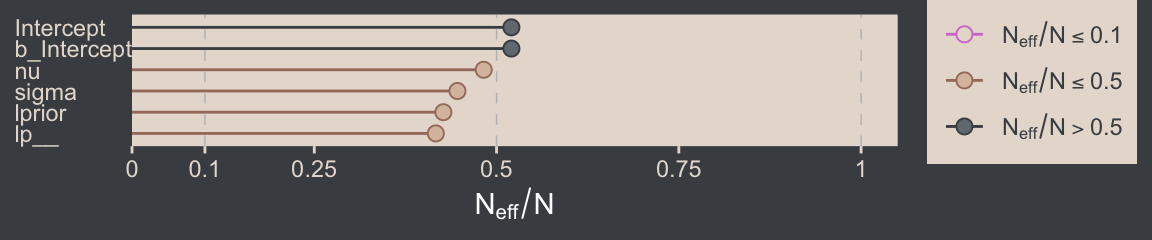

For all three parameters, the autocorrelations were near zero by lag 3 or 4. Not bad. The \(N_\textit{eff}/N\) ratios are okay.

# Rearrange the bayesplot color scheme again

color_scheme_set(scheme = bp[c(2:1, 4:3, 5:6)])

neff_ratio(fit16.2) |>

mcmc_neff(size = 2.5) +

yaxis_text(hjust = 0)

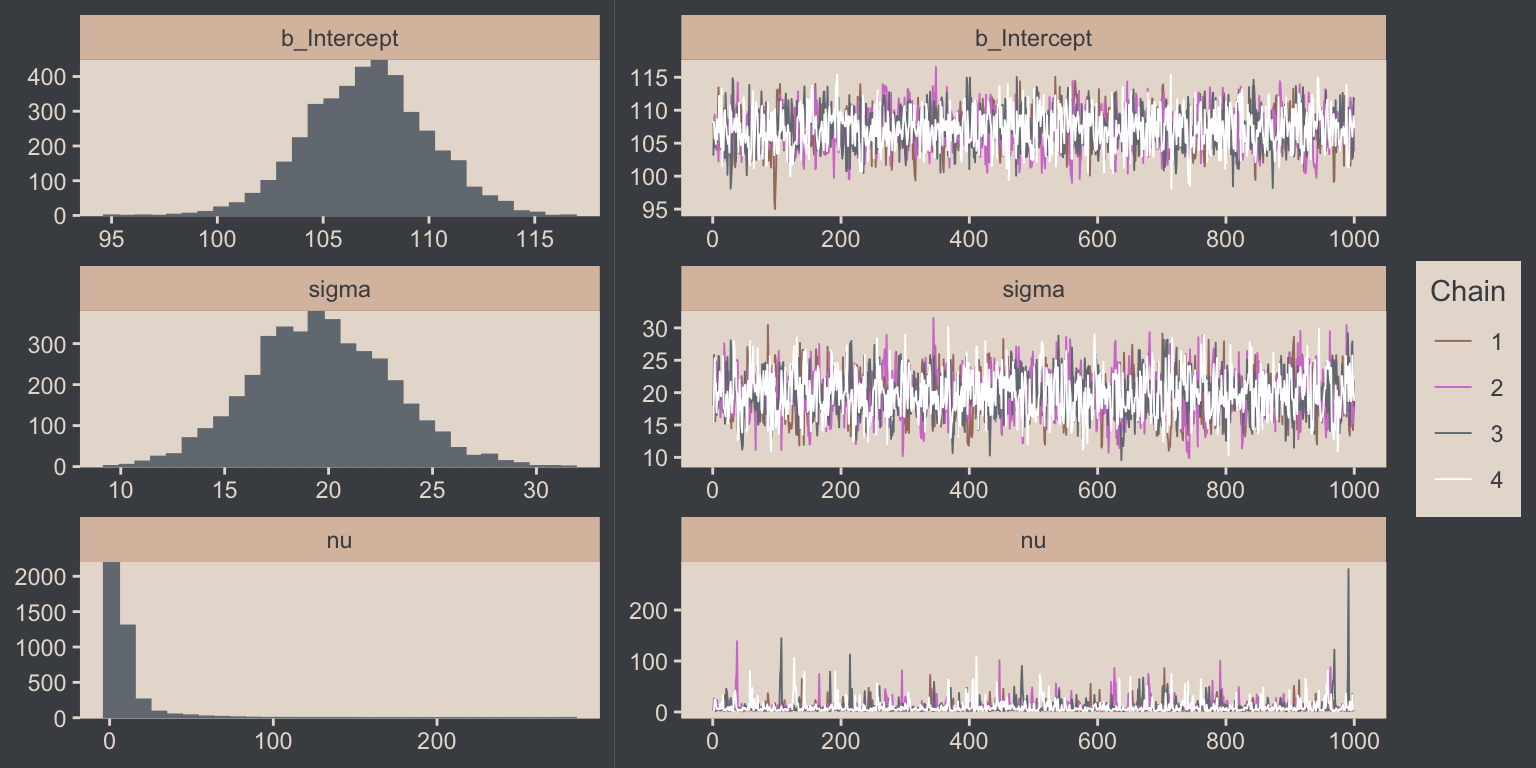

The trace plots look fine.

# Rearrange the bayesplot color scheme one more time

color_scheme_set(scheme = c("white", bp[c(2, 2, 2, 6, 3)]))

plot(fit16.2, widths = c(2, 3))

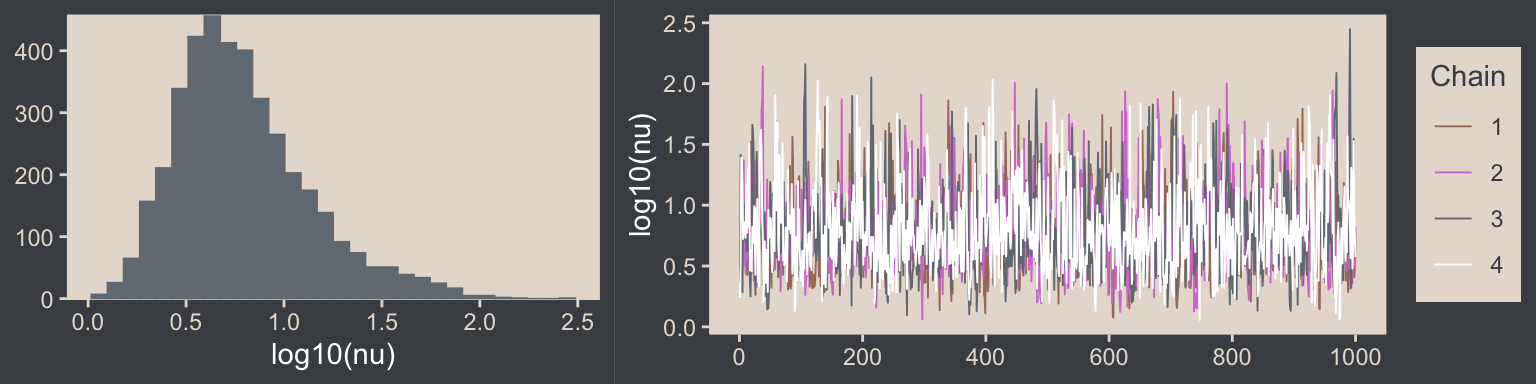

The values for nu are pretty skewed, but hopefully it makes sense to you why that might be the case. As with the pairs() plot, you can also transform parameters with the transformations argument. Here we use the log10() function for \(\nu\).

plot(fit16.2, transformations = list(nu = "log10"),

variable = "nu", widths = 2:3)

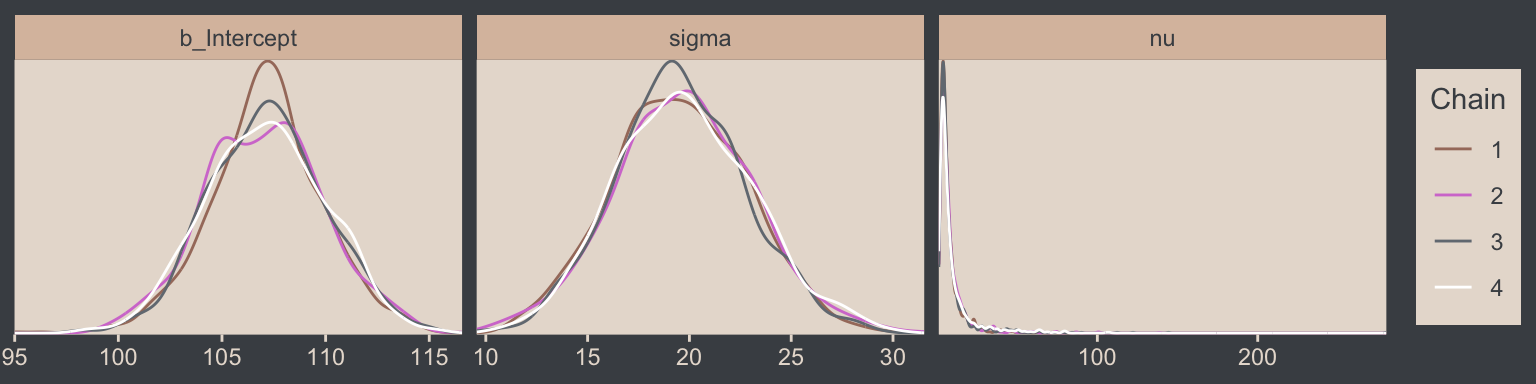

Here are the overlaid density plots (with \(\nu\) back in its un-transformed metric).

draws |>

mutate(chain = .chain) |>

mcmc_dens_overlay(pars = vars(b_Intercept:nu))

The \(\widehat R\) values are right where we like them.

brms::rhat(fit16.2, pars = c("b_Intercept", "sigma", "nu"))b_Intercept sigma nu

1.002250 1.001771 1.001341 You can use the stancode() function to return the Stan code underlying your brmsfit object.6

6 You can also extract this information from your brmsfit object with indexing like so: fit16.2$model.

stancode(fit16.2)// generated with brms 2.23.0

functions {

/* compute the logm1 link

* Args:

* p: a positive scalar

* Returns:

* a scalar in (-Inf, Inf)

*/

real logm1(real y) {

return log(y - 1.0);

}

/* compute the logm1 link (vectorized)

* Args:

* p: a positive vector

* Returns:

* a vector in (-Inf, Inf)

*/

vector logm1(vector y) {

return log(y - 1.0);

}

/* compute the inverse of the logm1 link

* Args:

* y: a scalar in (-Inf, Inf)

* Returns:

* a positive scalar

*/

real expp1(real y) {

return exp(y) + 1.0;

}

/* compute the inverse of the logm1 link (vectorized)

* Args:

* y: a vector in (-Inf, Inf)

* Returns:

* a positive vector

*/

vector expp1(vector y) {

return exp(y) + 1.0;

}

}

data {

int<lower=1> N; // total number of observations

vector[N] Y; // response variable

int prior_only; // should the likelihood be ignored?

real mean_y;

real sd_y;

real one_over_twentynine;

}

transformed data {

}

parameters {

real Intercept; // temporary intercept for centered predictors

real<lower=0> sigma; // dispersion parameter

real<lower=1> nu; // degrees of freedom or shape

}

transformed parameters {

// prior contributions to the log posterior

real lprior = 0;

lprior += normal_lpdf(Intercept | mean_y, sd_y * 100);

lprior += normal_lpdf(sigma | 0, sd_y)

- 1 * normal_lccdf(0 | 0, sd_y);

lprior += exponential_lpdf(nu | one_over_twentynine)

- 1 * exponential_lccdf(1 | one_over_twentynine);

}

model {

// likelihood including constants

if (!prior_only) {

// initialize linear predictor term

vector[N] mu = rep_vector(0.0, N);

mu += Intercept;

target += student_t_lpdf(Y | nu, mu, sigma);

}

// priors including constants

target += lprior;

}

generated quantities {

// actual population-level intercept

real b_Intercept = Intercept;

}Note the last line in the parameters block, “real<lower=1> nu; // degrees of freedom or shape.” By default, brms set the lower bound for \(\nu\) to 1. We won’t spend much more time discussing Stan code in this book. But if you’d like to learn more about the topic, I’ve written a short blog series on the Stan code underlying simple brms models, the first post of which you can find here.

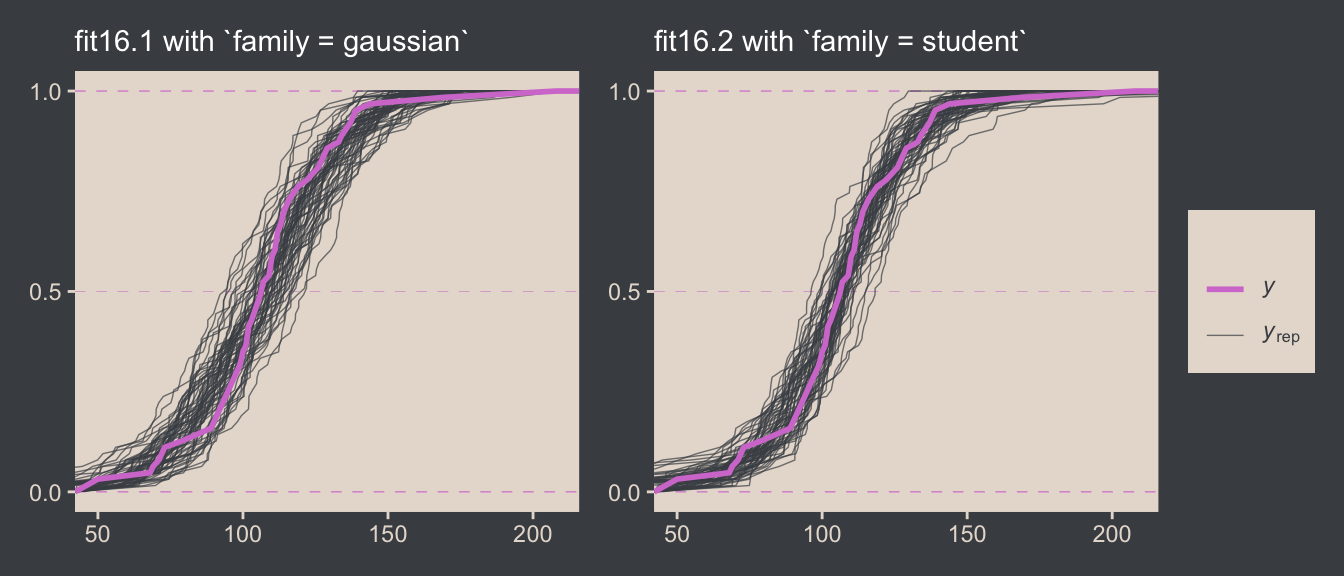

Just for kicks and giggles, the pp_check() offers us a handy way to compare the performance of our Gaussian fit16.2 and our Student’s \(t\) fit16.2. If we set type = "ecdf_overlay" within pp_check(), we’ll get the criterion Score displayed as a cumulative distribution function (CDF) rather than a typical density. Then, pp_check() presents CDF’s based on draws from the posterior for comparison. Just like with the default pp_check() plots, we like it when those simulated distributions mimic the one from the original data.

color_scheme_set(scheme = bp[c(1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 6)])

# `fit16.1` with the Gaussian

set.seed(16)

p1 <- pp_check(fit16.1, ndraws = n_lines, type = "ecdf_overlay") +

labs(subtitle = "fit16.1 with `family = gaussian`") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = range(my_data$Score)) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

# `fit16.2` with Student t

p2 <- pp_check(fit16.2, ndraws = n_lines, type = "ecdf_overlay") +

labs(subtitle = "fit16.2 with `family = student`") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = range(my_data$Score))

# Combine and display

p1 + p2

It’s subtle, but you might notice that the simulated CDFs from fit16.1 have shallower slopes in the middle when compared to the original data in the pink. However, the fit16.2-based simulated CDFs match up more closely with the original data. This suggests an edge for fit16.2. Revisiting our skills from Chapter 10, we might also compare their model weights.

model_weights(fit16.1, fit16.2) |>

round(digits = 6) fit16.1 fit16.2

0.000001 0.999999 Almost all the stacking weight (see Yao et al., 2018) went to fit16.2, our robust Student-\(t\) model. If you had to choose a single model with which to describe the data, the stacking weights lean heavily in favor of the Student-\(t\).7

7 Though do note that selecting a single model is at odds with the ethos behind the stacking weight paradigm.

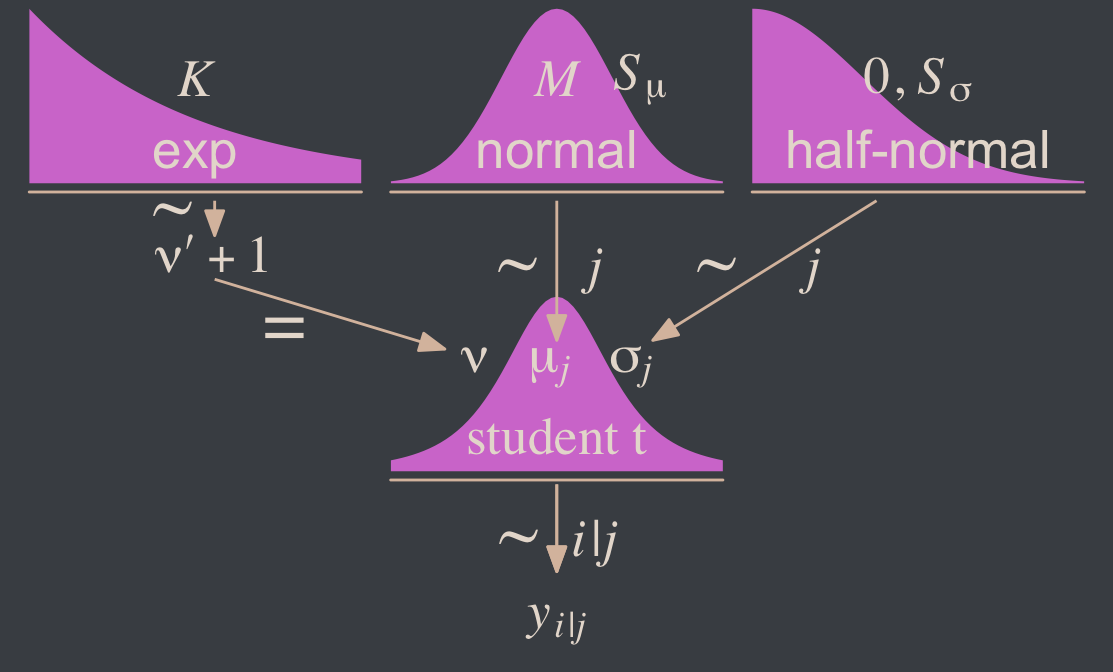

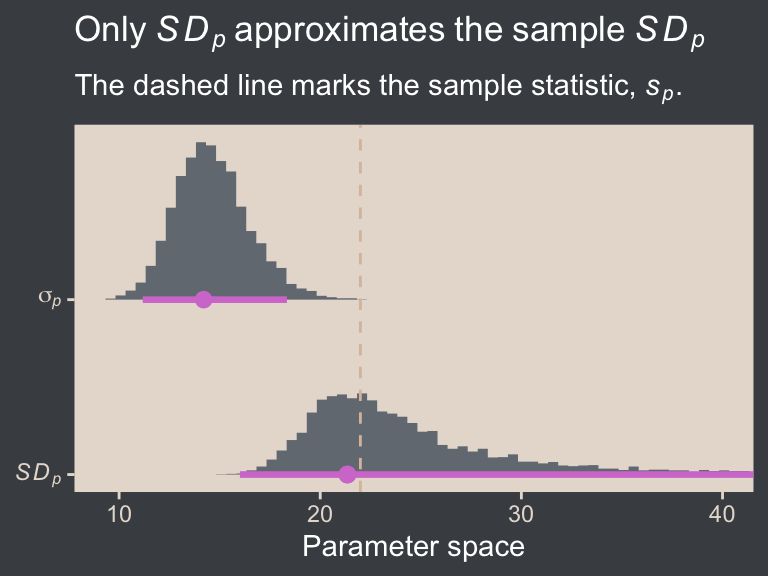

16.3 Two groups

When there are two groups, we estimate the mean and scale for each group. When using \(t\) distributions for robust estimation, we could also estimate the normality of each group separately. But because there usually are relatively few outliers, we will use a single normality parameter to describe both groups, so that the estimate of the normality is more stably estimated. (p. 468)

To get a sense of what this looks like, here’s our version of the model diagram in Figure 16.11.

# Exponential density

p1 <- tibble(x = seq(from = 0, to = 1, by = 0.01)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dexp(x, 2) / max(dexp(x, 2))))) +

geom_area(fill = bp[6]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0.5, y = 0.2,

label = "exp",

color = bp[5], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0.5, y = 0.6,

label = "italic(K)",

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = bp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Normal density

p2 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = bp[6]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = bp[5], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.5), y = 0.6,

label = c("italic(M)", "italic(S)[mu]"),

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = bp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Half-normal density

p3 <- tibble(x = seq(from = 0, to = 3, by = 0.01),

d = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x))) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = d)) +

geom_area(fill = bp[6]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.2,

label = "half-normal",

color = bp[5], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.6,

label = "0*','*~italic(S)[sigma]",

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = bp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Four annotated arrows

p4 <- tibble(x = c(0.43, 0.43, 1.5, 2.5),

y = c(1, 0.55, 1, 1),

xend = c(0.43, 1.15, 1.5, 1.8),

yend = c(0.8, 0.15, 0.2, 0.2)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, xend = xend,

y = y, yend = yend)) +

geom_segment(arrow = my_arrow, color = bp[4]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0.3, 0.65, 1.38, 1.62, 2, 2.3), y = c(0.92, 0.25, 0.6, 0.6, 0.6, 0.6),

label = c("'~'", "'='", "'~'", "italic(j)", "'~'", "italic(j)"),

size = c(10, 10, 10, 7, 10, 7),

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0.43, y = 0.7,

label = "nu*minute+1",

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

xlim(0, 3) +

theme_void()

# Student-t density

p5 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dt(x, 3) / max(dt(x, 3))))) +

geom_area(fill = bp[6]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "student t",

color = bp[5], family = "Times", size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.6,

label = "nu~~~mu[italic(j)]~~~sigma[italic(j)]",

color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = bp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# The final annotated arrow

p6 <- tibble(x = c(0.375, 0.625),

y = c(1/3, 1/3),

label = c("'~'", "italic(i)*'|'*italic(j)")) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = c(10, 7)) +

geom_segment(x = 0.5, xend = 0.5,

y = 1, yend = 0,

arrow = my_arrow, color = bp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Some text

p7 <- tibble(x = 0.5,

y = 0.5,

label = "italic(y)[italic(i)*'|'*italic(j)]") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = bp[5], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Define the layout

layout <- c(

area(t = 1, b = 2, l = 1, r = 2),

area(t = 1, b = 2, l = 3, r = 4),

area(t = 1, b = 2, l = 5, r = 6),

area(t = 4, b = 5, l = 3, r = 4),

area(t = 3, b = 4, l = 1, r = 6),

area(t = 6, b = 6, l = 3, r = 4),

area(t = 7, b = 7, l = 3, r = 4))

# Combine, augment, and display

(p1 + p2 + p3 + p5 + p4 + p6 + p7) +

plot_layout(design = layout) &

ylim(0, 1) &

theme(plot.margin = margin(0, 5.5, 0, 5.5))

Since we subset the data, earlier, we’ll just reload it to get the full data set.

my_data <- read_csv("data.R/TwoGroupIQ.csv")This time, we’ll compute mean_y and sd_y from the full data.

mean_y <- mean(my_data$Score) # 107.8413

sd_y <- sd(my_data$Score) # 25.4452

stanvars <- stanvar(mean_y, name = "mean_y") +

stanvar(sd_y, name = "sd_y") +

stanvar(1/29, name = "one_over_twentynine")Within the brms framework, Bürkner calls it distributional modeling when you model more than the mean. Since we’re now modeling both \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\), we’re fitting a distributional model. When doing so with brms, you typically wrap your formula syntax into the bf() function. It’s also important to know that when modeling \(\sigma\), brms defaults to modeling its log. So we’ll use log(sd_y) in its prior. For more on all this, see Bürkner’s (2022a) vignette, Estimating distributional models with brms.

fit16.3 <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = student,

bf(Score ~ 0 + Group,

sigma ~ 0 + Group),

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 100), class = b),

prior(normal(0, log(sd_y)), class = b, dpar = sigma),

prior(exponential(one_over_twentynine), class = nu)),

chains = 4, cores = 4,

stanvars = stanvars,

seed = 16,

file = "fits/fit16.03")Did you catch our ~ 0 + Group syntax? That suppressed the usual intercept for our estimates of both \(\mu\) and \(\log (\sigma)\). Since Group is a categorical variable, that results in brm() fitting separate intercepts for each category. This is our brms analogue to the x[i] syntax Kruschke mentioned on page 468. It’s what allowed us to estimate \(\mu_j\) and \(\log (\sigma_j)\).8

8 If you really wanted to model \(\sigma\) with the identity link, you could set family = brmsfamily(family = "gaussian", link_sigma = "identity").

Let’s look at the model summary.

print(fit16.3) Family: student

Links: mu = identity; sigma = log

Formula: Score ~ 0 + Group

sigma ~ 0 + Group

Data: my_data (Number of observations: 120)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 2000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 4000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

GroupPlacebo 99.28 1.81 95.65 102.77 1.00 4221 2345

GroupSmartDrug 107.10 2.54 102.13 112.12 1.00 4445 2684

sigma_GroupPlacebo 2.38 0.15 2.08 2.69 1.00 3764 2877

sigma_GroupSmartDrug 2.84 0.15 2.54 3.12 1.00 3188 3014

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

nu 3.55 1.37 1.86 7.16 1.00 2742 2886

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Remember that the \(\sigma\)’s are now in the log scale. If you want a quick conversion, you might just exponentiate the point estimates from fixef().

fixef(fit16.3)[3:4, 1] |> exp() sigma_GroupPlacebo sigma_GroupSmartDrug

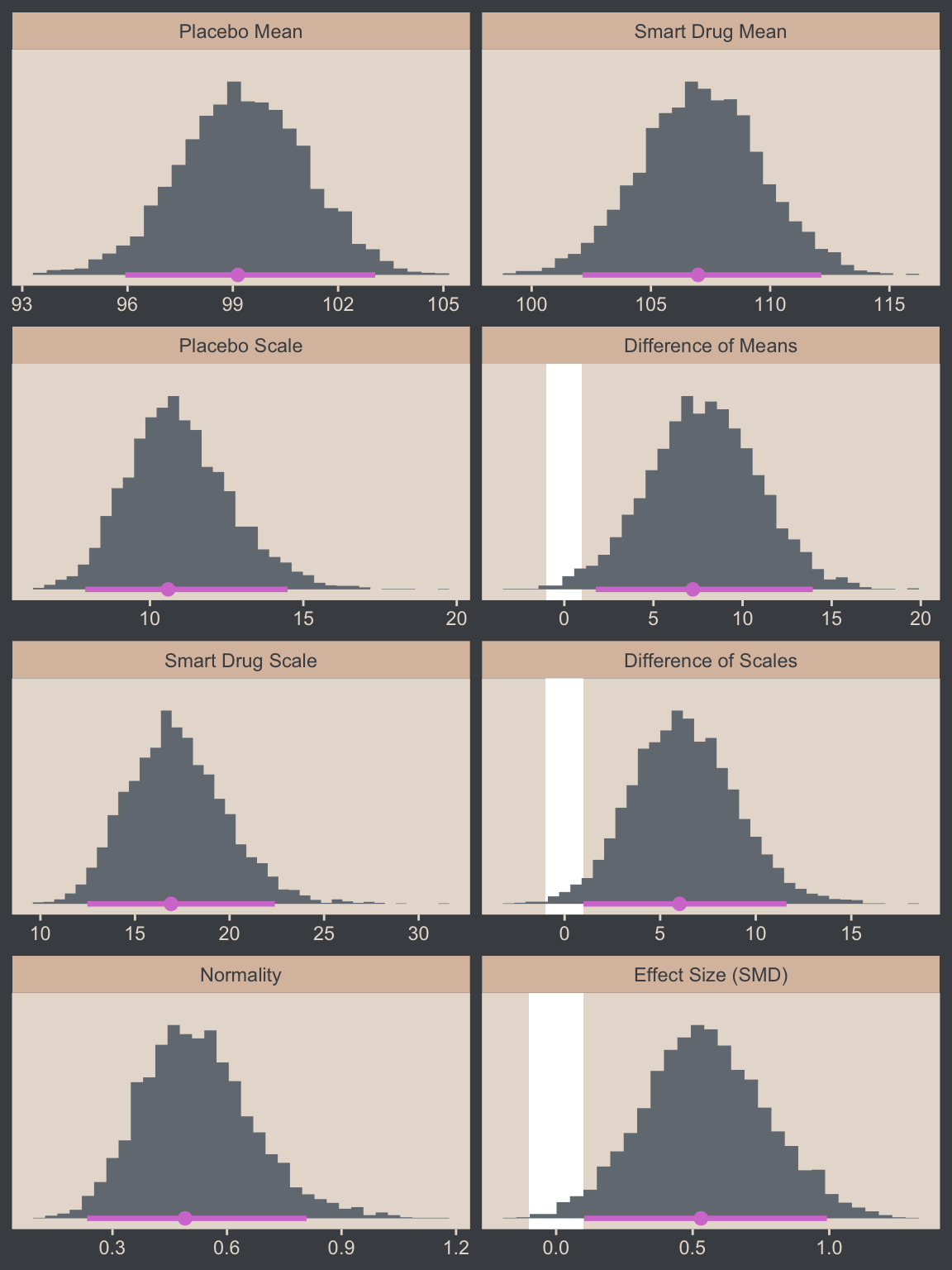

10.83393 17.03526 But please don’t stop there. Get your hands dirty with the full posterior. Speaking of which, if we want to make the histograms in Figure 16.12, we’ll need to first extract the posterior draws.

draws <- as_draws_df(fit16.3)

glimpse(draws)Rows: 4,000

Columns: 10

$ b_GroupPlacebo <dbl> 99.16719, 100.54338, 95.65252, 102.03916, 100.36230, 101.05343, 99.24068, 99.60996, 99.63029, 98.…

$ b_GroupSmartDrug <dbl> 104.3200, 108.2249, 109.7512, 106.6429, 106.3699, 107.4756, 105.4800, 105.3788, 107.4015, 107.294…

$ b_sigma_GroupPlacebo <dbl> 2.187976, 2.437288, 2.421437, 2.285885, 2.305314, 2.189126, 2.473225, 2.424427, 2.418429, 2.31252…

$ b_sigma_GroupSmartDrug <dbl> 2.718163, 2.831951, 2.845662, 2.740732, 2.852650, 2.843634, 2.884846, 2.860414, 2.836407, 2.73560…

$ nu <dbl> 1.781909, 4.974685, 2.557897, 3.525888, 1.983768, 3.042144, 2.826849, 3.089014, 3.840557, 3.13694…

$ lprior <dbl> -25.40045, -25.60276, -25.51948, -25.48958, -25.47336, -25.48022, -25.55344, -25.54288, -25.56023…

$ lp__ <dbl> -551.5071, -549.5005, -551.6565, -550.2347, -550.9234, -549.5740, -549.3824, -548.6740, -548.3060…

$ .chain <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1…

$ .iteration <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27…

$ .draw <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27…Along with transforming the metrics of a few of the parameters, we may as well rename them to match those in the text.

draws <- draws |>

mutate(`Placebo Mean` = b_GroupPlacebo,

`Smart Drug Mean` = b_GroupSmartDrug,

# We need to transform the next three parameters

`Placebo Scale` = b_sigma_GroupPlacebo |> exp(),

`Smart Drug Scale` = b_sigma_GroupSmartDrug |> exp(),

Normality = nu |> log10()) |>

mutate(`Difference of Means` = `Smart Drug Mean` - `Placebo Mean`,

`Difference of Scales` = `Smart Drug Scale` - `Placebo Scale`,

`Effect Size (SMD)` = (`Smart Drug Mean` - `Placebo Mean`) / sqrt((`Smart Drug Scale`^2 + `Placebo Scale`^2) / 2)) |>

select(.draw, `Placebo Mean`:`Effect Size (SMD)`)

glimpse(draws)Rows: 4,000

Columns: 9

$ .draw <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27…

$ `Placebo Mean` <dbl> 99.16719, 100.54338, 95.65252, 102.03916, 100.36230, 101.05343, 99.24068, 99.60996, 99.63029, 98.…

$ `Smart Drug Mean` <dbl> 104.3200, 108.2249, 109.7512, 106.6429, 106.3699, 107.4756, 105.4800, 105.3788, 107.4015, 107.294…

$ `Placebo Scale` <dbl> 8.917143, 11.441965, 11.262026, 9.834386, 10.027324, 8.927411, 11.860636, 11.295758, 11.228206, 1…

$ `Smart Drug Scale` <dbl> 15.15246, 16.97856, 17.21294, 15.49832, 17.33366, 17.17808, 17.90081, 17.46875, 17.05438, 15.4191…

$ Normality <dbl> 0.2508856, 0.6967656, 0.4078830, 0.5472685, 0.2974909, 0.4831798, 0.4513026, 0.4898199, 0.5843942…

$ `Difference of Means` <dbl> 5.152785, 7.681511, 14.098712, 4.603699, 6.007628, 6.422195, 6.239327, 5.768851, 7.771189, 9.0924…

$ `Difference of Scales` <dbl> 6.2353163, 5.5365961, 5.9509188, 5.6639361, 7.3063359, 8.2506731, 6.0401779, 6.1729925, 5.8261757…

$ `Effect Size (SMD)` <dbl> 0.4144754, 0.5305865, 0.9693114, 0.3547015, 0.4242719, 0.4691451, 0.4109118, 0.3921797, 0.5382373…Now we’re ready for the bulk of Figure 16.12.

# Save the factor levels

levels <- c("Placebo Mean", "Smart Drug Mean", "Placebo Scale", "Difference of Means",

"Smart Drug Scale", "Difference of Scales", "Normality", "Effect Size (SMD)")

# We'll use this to mark off the ROPEs as white strips in the background

rope <- tibble(name = factor(c("Difference of Means", "Difference of Scales", "Effect Size (SMD)"),

levels = levels),

xmin = c(-1, -1, -0.1),

xmax = c(1, 1, 0.1))

# Here are the primary data

draws |>

pivot_longer(cols = -.draw) |>

# This isn't necessary, but it arranged our subplots like those in the text

mutate(name = factor(name, levels = levels)) |>

# Plot

ggplot() +

geom_rect(data = rope,

aes(xmin = xmin, xmax = xmax,

ymin = -Inf, ymax = Inf),

color = "transparent", fill = "white") +

stat_histinterval(aes(x = value, y = 0),

point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = bp[6], fill = bp[2],

normalize = "panels") +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab(NULL) +

facet_wrap(~ name, ncol = 2, scales = "free")

You’ll note we’ve clarified the effect size displayed is a standardized mean difference (SMD). This is because though effect sizes are often applied to mean differences, there are many other kinds of effect sizes. For example, we could also consider presenting the difference in \(\sigma\) (third row from the bottom, right column) in one of the effect-size metrics discussed in Senior et al. (2020), such as \(\sigma\) ratios (\(\sigma_2 / \sigma_1\)) or the logarithm of \(\sigma\) ratios (\(\log(\sigma_2 / \sigma_1)\)).

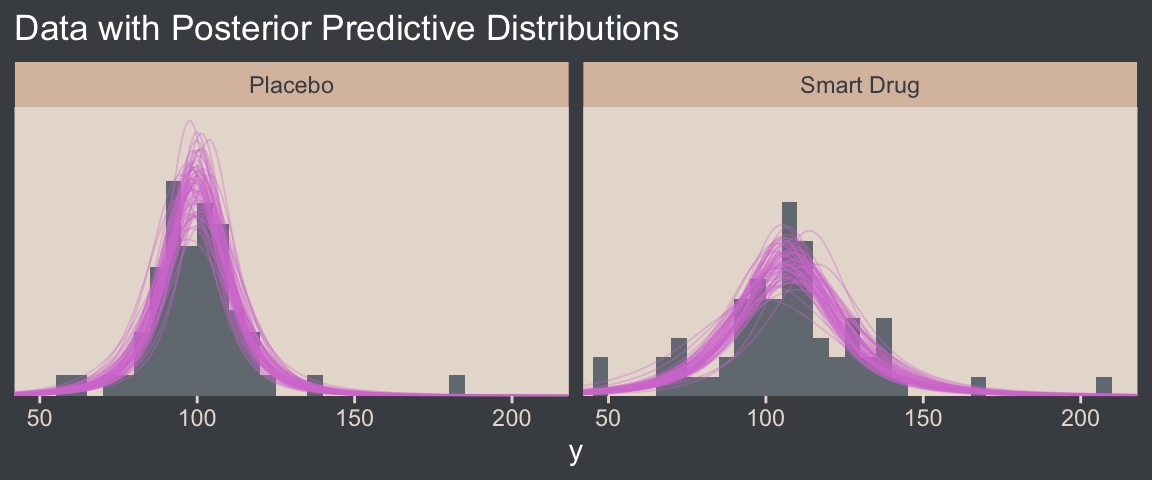

Now let’s make the upper two panels in the right column of Figure 16.12.

You might note a few things in our wrangling code. First, in the mutate() function we defined the density values for the two Group conditions one at a time. If you look carefully within those definitions, you’ll see we used 10^Normality for the df argument, rather than just Normality. Why? Remember how a few code blocks up we transformed the original nu column to Normality by placing it within log10()? Well, if you want to undo that, you have to take 10 to the power of Normality. Next, notice that we subset the draws tibble with select(). This wasn’t technically necessary, but it made the next line easier. Finally, with the pivot_longer() function, we transformed the Placebo and Smart Drug columns into an index column strategically named Group, which matched up with the original my_data data, and a density column, which contained the actual density values for the lines.

I know. That’s a lot to take in. If you’re confused, run the lines in the code one at a time to see how they work. But anyway, here’s the final result!

# How many credible density lines would you like?

n_lines <- 63

# Setting the seed makes the results from `slice_sample()` reproducible

set.seed(16)

# Wrangle

draws |>

slice_sample(n = n_lines) |>

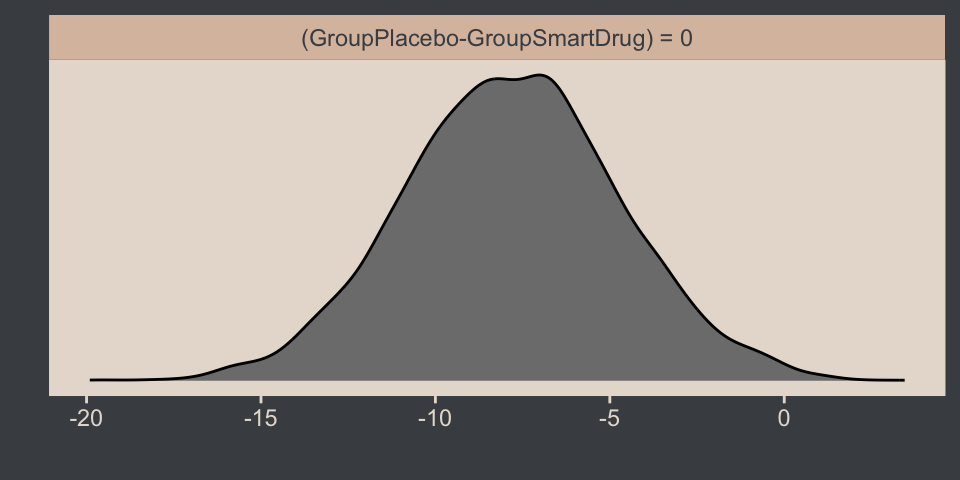

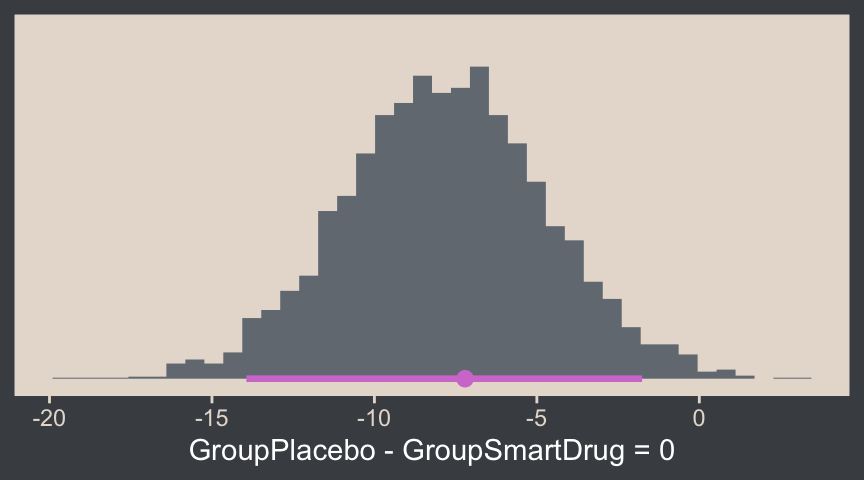

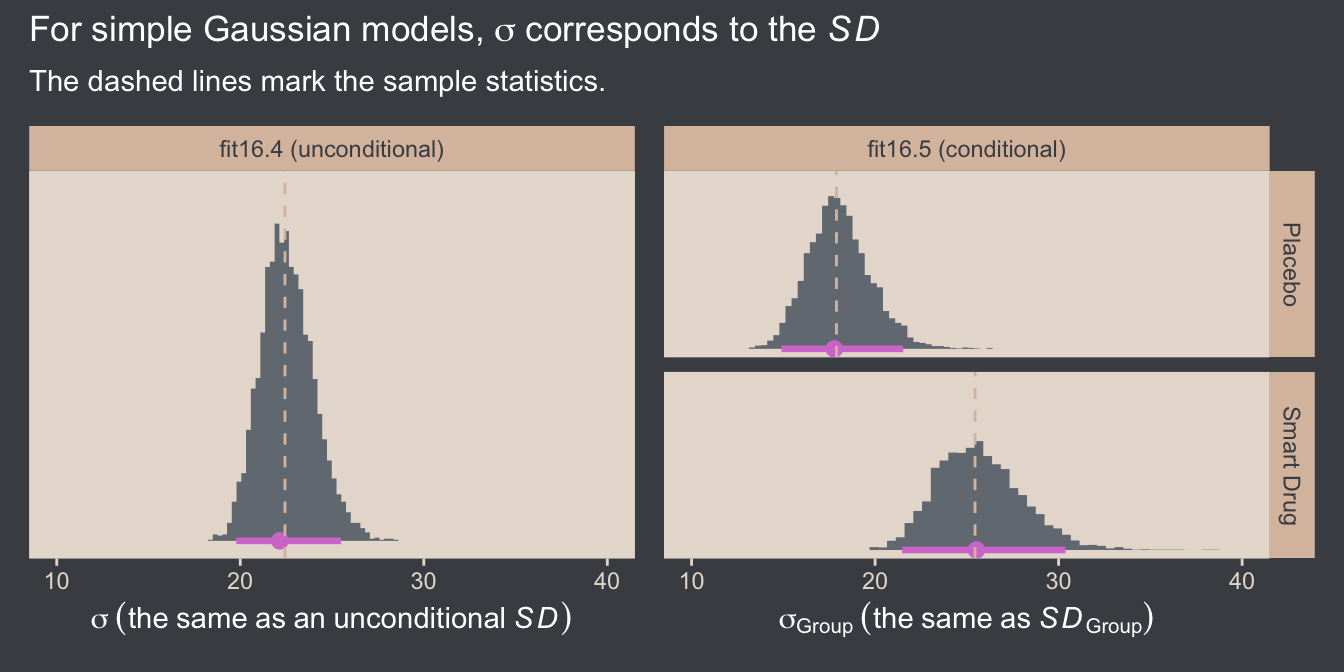

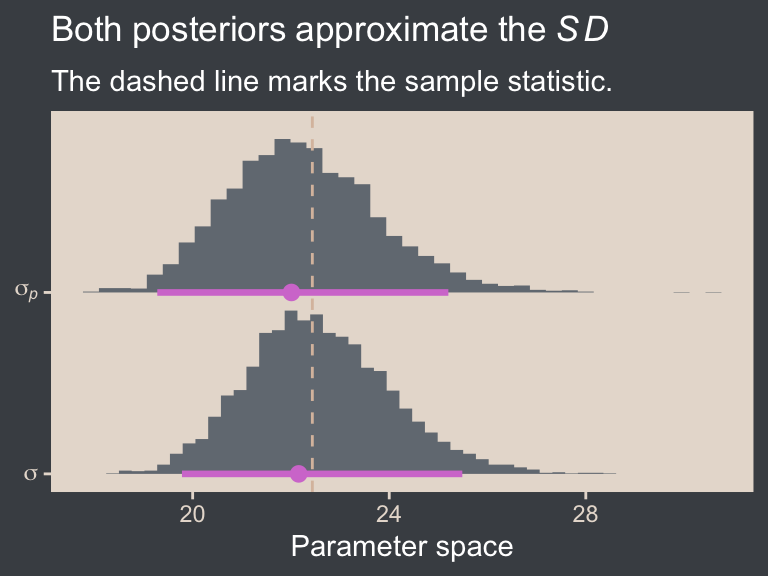

expand_grid(Score = seq(from = 40, to = 250, by = 1)) |>