library(tidyverse)

library(palettetown)

library(ggridges)

library(patchwork)

library(brms)

library(bayesplot)

library(tidybayes)19 Metric Predicted Variable with One Nominal Predictor

This chapter considers data structures that consist of a metric predicted variable and a nominal predictor…. This type of data structure can arise from experiments or from observational studies. In experiments, the researcher assigns the categories (at random) to the experimental subjects. In observational studies, both the nominal predictor value and the metric predicted value are generated by processes outside the direct control of the researcher. In either case, the same mathematical description can be applied to the data (although causality is best inferred from experimental intervention).

The traditional treatment of this sort of data structure is called single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), or sometimes one-way ANOVA. Our Bayesian approach will be a hierarchical generalization of the traditional ANOVA model. The chapter will also consider the situation in which there is also a metric predictor that accompanies the primary nominal predictor. The metric predictor is sometimes called a covariate, and the traditional treatment of this data structure is called analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The chapter also considers generalizations of the traditional models, because it is straight forward in Bayesian software to implement heavy-tailed distributions to accommodate outliers, along with hierarchical structure to accommodate heterogeneous variances in the different groups, etc. (Kruschke, 2015, pp. 553–554)

19.1 Describing multiple groups of metric data

Load the primary packages.

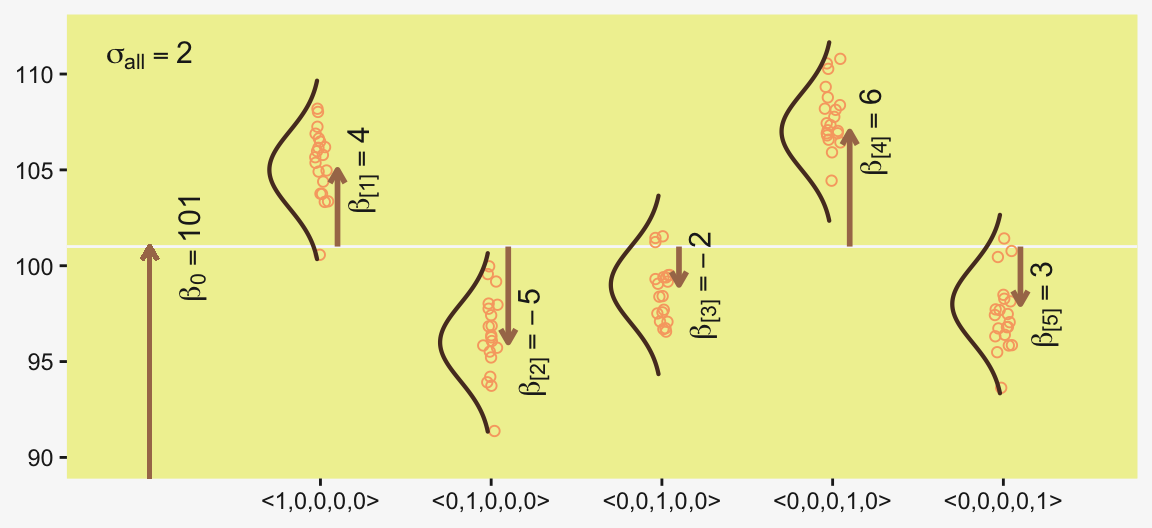

Figure 19.1 illustrates the conventional description of grouped metric data. Each group is represented as a position on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis represents the variable to be predicted by group membership. The data are assumed to be normally distributed within groups, with equal standard deviation in all groups. The group means are deflections from overall baseline, such that the deflections sum to zero. Figure 19.1 provides a specific numerical example, with data that were randomly generated from the model. (p. 554)

We’ll want a custom data-generating function for our primary group data.

generate_data <- function(seed, mean) {

set.seed(seed)

rnorm(n, mean = grand_mean + mean, sd = 2)

}

n <- 20

grand_mean <- 101

d <- tibble(group = 1:5,

deviation = c(4, -5, -2, 6, -3)) |>

mutate(d = map2(.x = group, .y = deviation, .f = generate_data)) |>

unnest(d) |>

mutate(iteration = rep(1:n, times = 5))

glimpse(d)Rows: 100

Columns: 4

$ group <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,…

$ deviation <dbl> 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5, -5…

$ d <dbl> 103.74709, 105.36729, 103.32874, 108.19056, 105.65902, 103.35906, 105.97486, 106.47665, 106.15156, 104.38922, …

$ iteration <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, …Here we’ll make a tibble containing the necessary data for the rotated Gaussians. As far as I can tell, Kruschke’s Gaussians only span to the bounds of percentile-based 98% intervals. We partition off those bounds for each group by the ll and ul columns in the first mutate() function. In the second mutate(), we expand the dataset to include a sequence of 100 values between those lower- and upper-limit points. In the third mutate(), we feed those points into the dnorm() function, with group-specific means and a common sd.

densities <- d |>

distinct(group, deviation) |>

mutate(ll = qnorm(0.01, mean = grand_mean + deviation, sd = 2),

ul = qnorm(0.99, mean = grand_mean + deviation, sd = 2)) |>

mutate(d = map2(.x = ll, .y = ul,

.f = \(ll, ul) seq(from = ll, to = ul, length.out = 100))) |>

mutate(density = map2(.x = d, .y = grand_mean + deviation,

.f = \(d, m) dnorm(x = d, mean = m, sd = 2))) |>

unnest(c(d, density))

head(densities)# A tibble: 6 × 6

group deviation ll ul d density

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 4 100. 110. 100. 0.0133

2 1 4 100. 110. 100. 0.0148

3 1 4 100. 110. 101. 0.0165

4 1 4 100. 110. 101. 0.0183

5 1 4 100. 110. 101. 0.0203

6 1 4 100. 110. 101. 0.0224We’ll need two more supplementary tibbles to add the flourishes to the plot. The d_arrow tibble will specify our light-gray arrows. The text tibble will contain our annotation information.

d_arrow <- tibble(d = grand_mean,

group = 1:5,

deviation = c(4, -5, -2, 6, -3),

offset = 0.1)

head(d_arrow)# A tibble: 5 × 4

d group deviation offset

<dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

1 101 1 4 0.1

2 101 2 -5 0.1

3 101 3 -2 0.1

4 101 4 6 0.1

5 101 5 -3 0.1d_text <- tibble(

d = grand_mean,

group = c(0:5, 0),

deviation = c(0, 4, -5, -2, 6, -3, 10),

offset = rep(c(1/4, 0), times = c(6, 1)),

angle = rep(c(90, 0), times = c(6, 1)),

label = c("beta[0]==101", "beta['[1]']==4","beta['[2]']==-5", "beta['[3]']==-2",

"beta['[4]']==6", "beta['[5]']==3", "sigma['all']==2"))

head(d_text)# A tibble: 6 × 6

d group deviation offset angle label

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 101 0 0 0.25 90 beta[0]==101

2 101 1 4 0.25 90 beta['[1]']==4

3 101 2 -5 0.25 90 beta['[2]']==-5

4 101 3 -2 0.25 90 beta['[3]']==-2

5 101 4 6 0.25 90 beta['[4]']==6

6 101 5 -3 0.25 90 beta['[5]']==3 We’re almost ready to plot. Before we do, let’s talk color and theme. For this chapter, we’ll take our color palette from the palettetown package (Lucas, 2016), which provides an array of color palettes inspired by Pokémon. Our color palette will be #17, which is based on Pidgeotto.

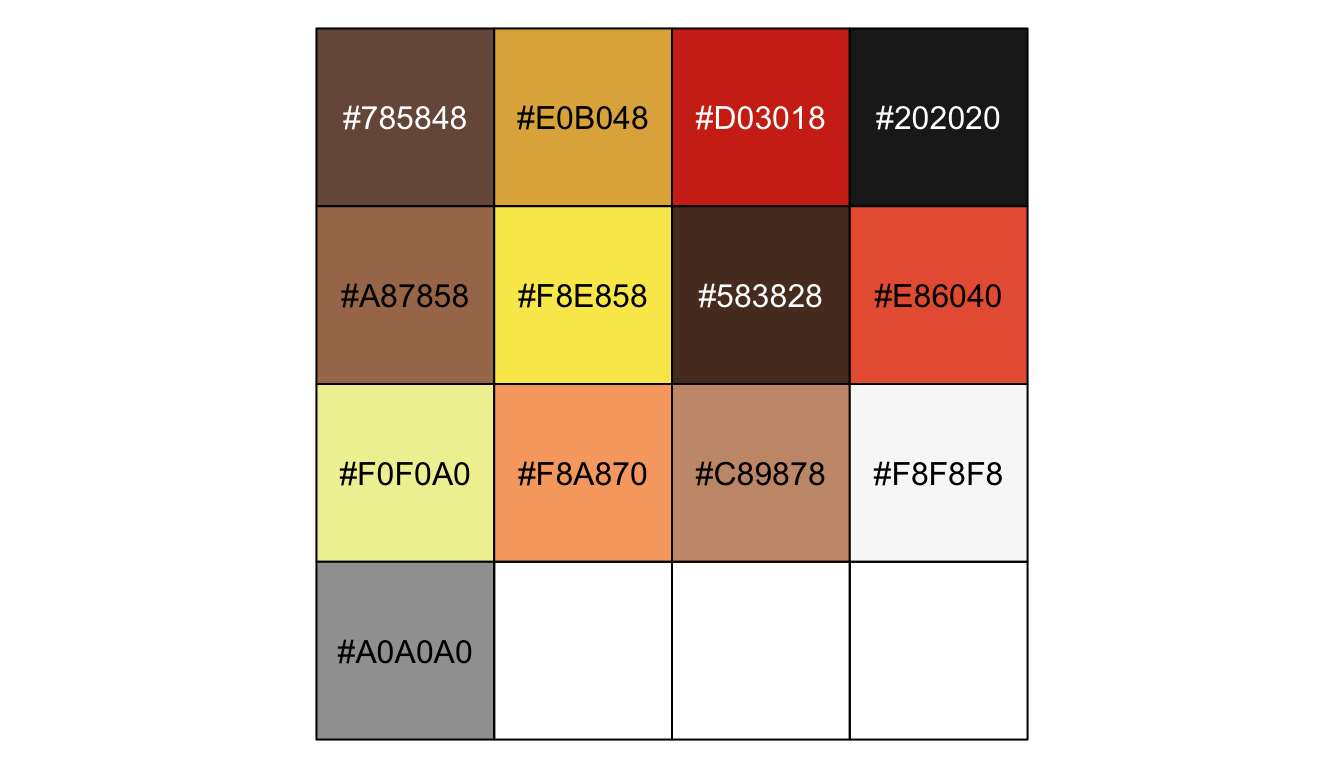

scales::show_col(pokepal(pokemon = 17))

pp <- pokepal(pokemon = 17)

pp [1] "#785848" "#E0B048" "#D03018" "#202020" "#A87858" "#F8E858" "#583828" "#E86040" "#F0F0A0" "#F8A870" "#C89878" "#F8F8F8"

[13] "#A0A0A0"Our overall plot theme will be based on the default theme_grey() with a good number of adjustments.

theme_set(

theme_grey() +

theme(text = element_text(color = pp[4]),

axis.text = element_text(color = pp[4]),

axis.ticks = element_line(color = pp[4]),

legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.box.background = element_blank(),

legend.key = element_rect(fill = pp[9]),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = pp[9], color = pp[9]),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = pp[12], color = pp[12]),

strip.background = element_rect(fill = alpha(pp[2], 1/3), color = "transparent"),

strip.text = element_text(color = pp[4]))

)Now make Figure 19.1.

d |>

ggplot(aes(x = d, y = group, group = group)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = grand_mean, color = pp[12]) +

geom_jitter(alpha = 4/4, color = pp[10], height = 0.05, shape = 1) +

# The Gaussians

geom_ridgeline(data = densities,

aes(height = -density),

color = pp[7], fill = "transparent",

linewidth = 3/4, min_height = NA, scale = 3/2) +

# The small arrows

geom_segment(data = d_arrow,

aes(xend = d + deviation,

y = group + offset, yend = group + offset),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.2, "cm")),

color = pp[5], linewidth = 1) +

# The large arrow on the left

geom_segment(aes(x = 80, xend = grand_mean,

y = 0, yend = 0),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.2, "cm")),

color = pp[5], linewidth = 3/4) +

# The text

geom_text(data = d_text,

aes(x = grand_mean + deviation, y = group + offset,

label = label, angle = angle),

color = pp[4], parse = TRUE, size = 4) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = 1:5,

labels = c("<1,0,0,0,0>", "<0,1,0,0,0>", "<0,0,1,0,0>", "<0,0,0,1,0>", "<0,0,0,0,1>")) +

xlab(NULL) +

coord_flip(xlim = c(90, 112),

ylim = c(-0.2, 5.5))

The descriptive model presented in Figure 19.1 is the traditional one used by classical ANOVA (which is described a bit more in the next section). More general models are straight forward to implement in Bayesian software. For example, outliers could be accommodated by using heavy-tailed noise distributions (such as a \(t\) distribution) instead of a normal distribution, and different groups could be given different standard deviations. (p. 556)

19.2 Traditional analysis of variance

The terminology, “analysis of variance,” comes from a decomposition of overall data variance into within-group variance and between-group variance (Fisher, 1925). Algebraically, the sum of squared deviations of the scores from their overall mean equals the sum of squared deviations of the scores from their respective group means plus the sum of squared deviations of the group means from the overall mean. In other words, the total variance can be partitioned into within-group variance plus between-group variance. Because one definition of the word “analysis” is separation into constituent parts, the term ANOVA accurately describes the underlying algebra in the traditional methods. That algebraic relation is not used in the hierarchical Bayesian approach presented here. The Bayesian method can estimate component variances, however. Therefore, the Bayesian approach is not ANOVA, but is analogous to ANOVA. (p. 556)

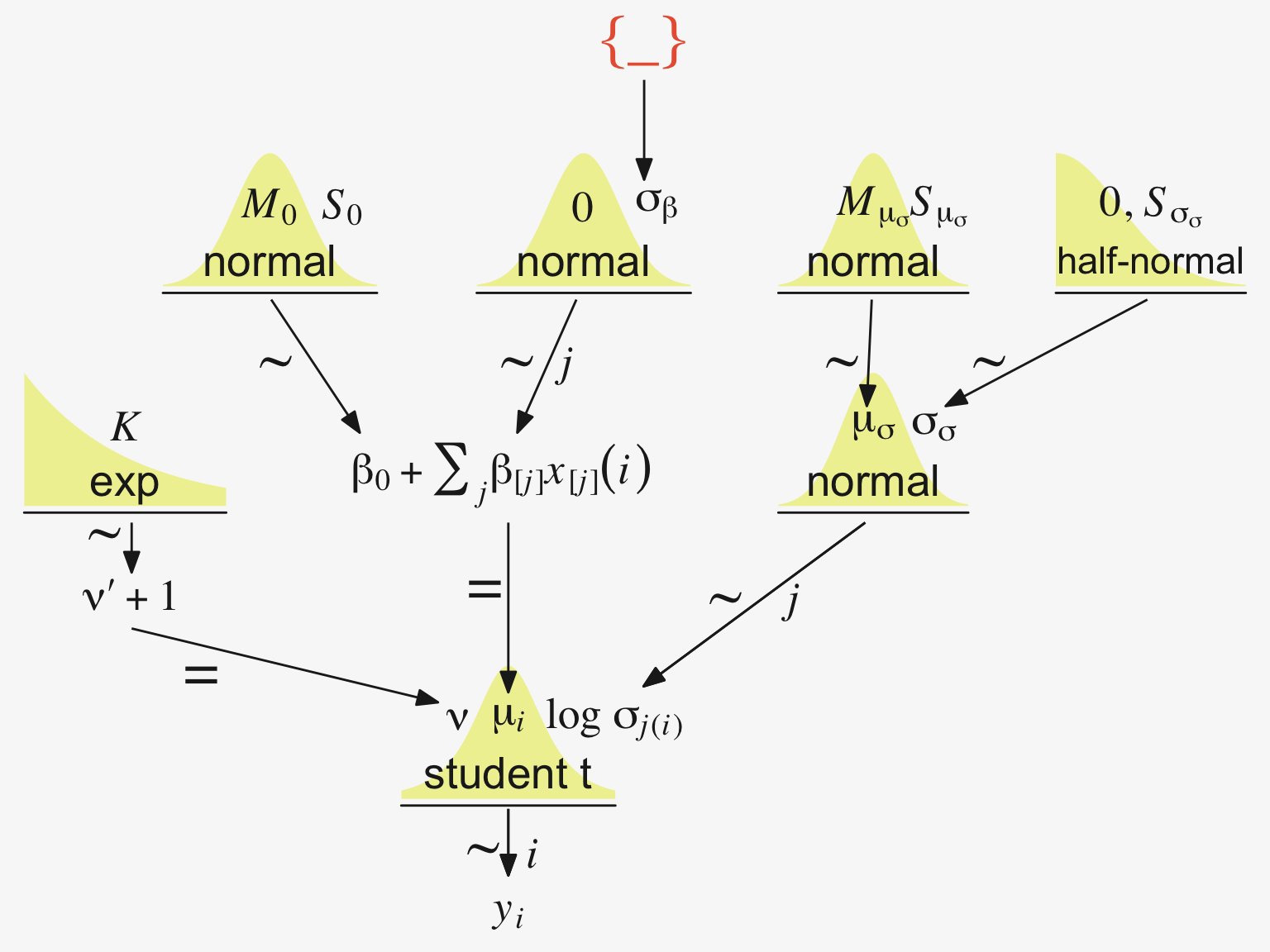

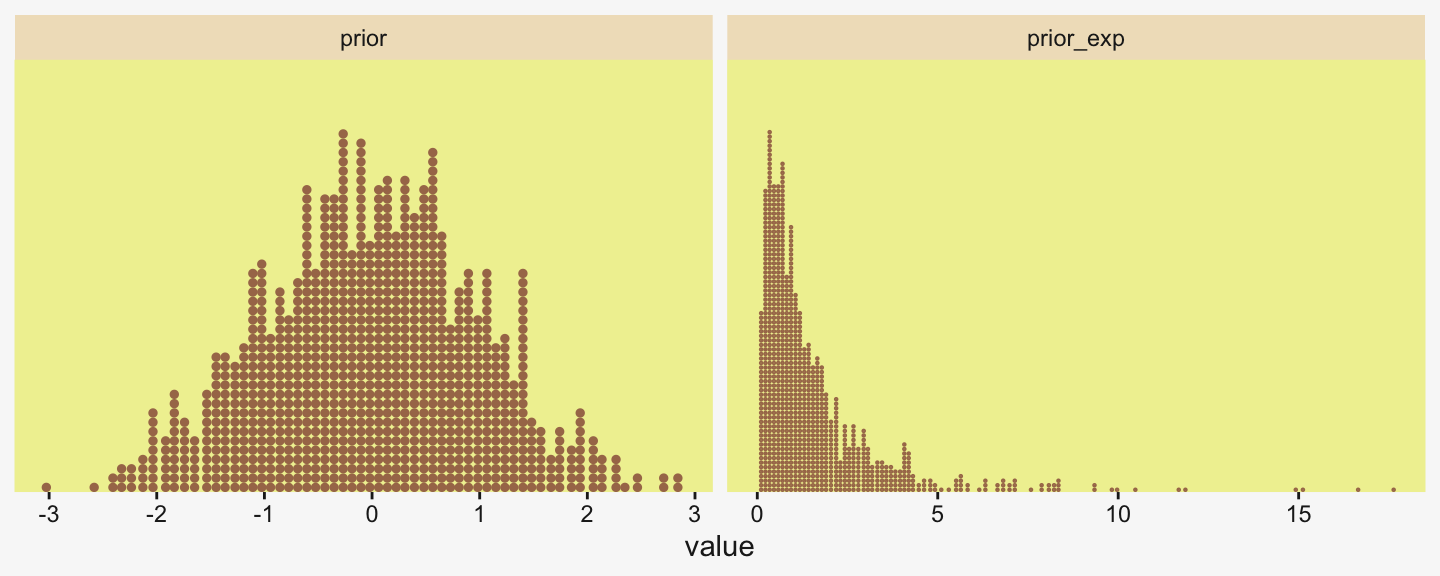

19.3 Hierarchical Bayesian approach

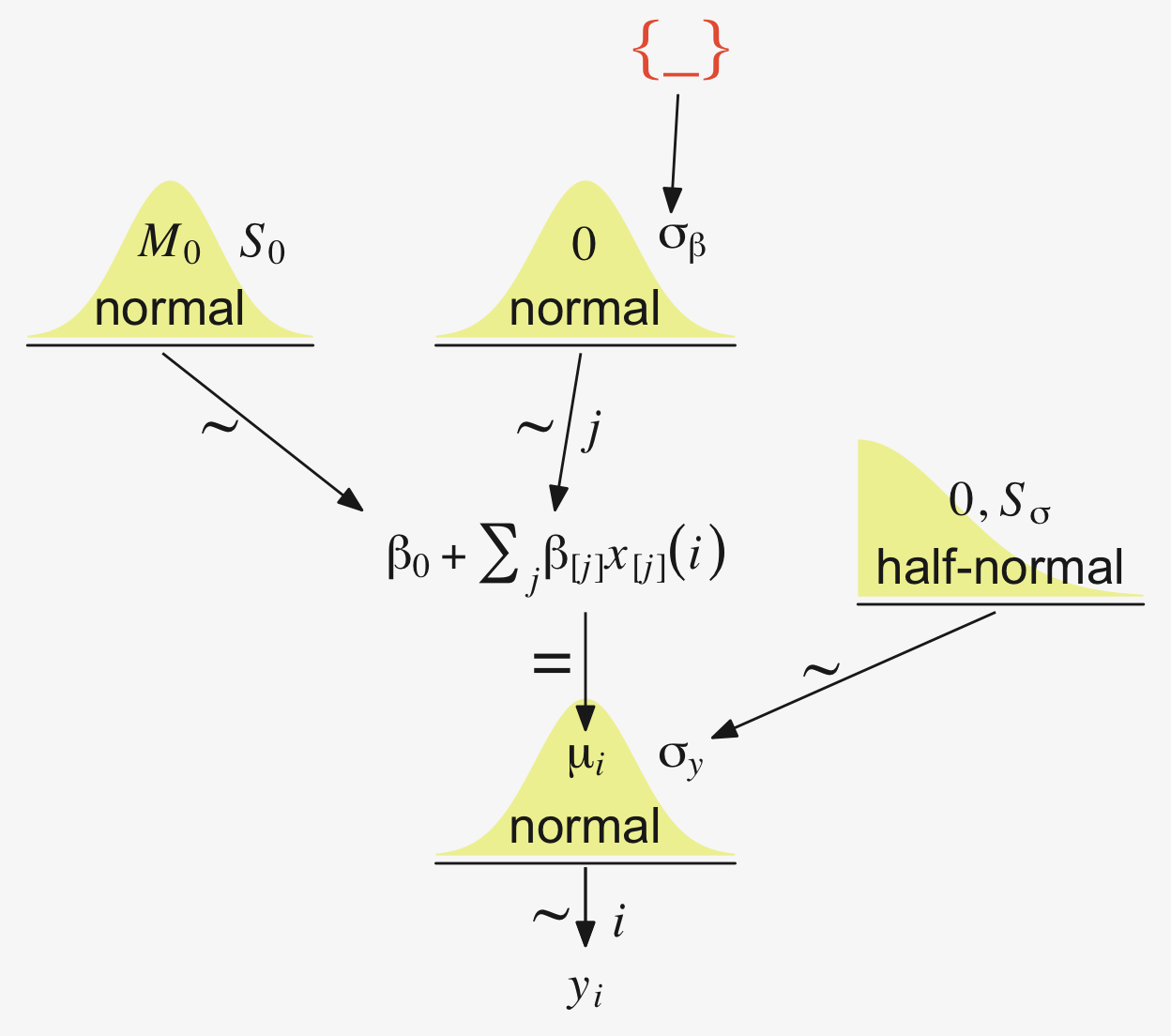

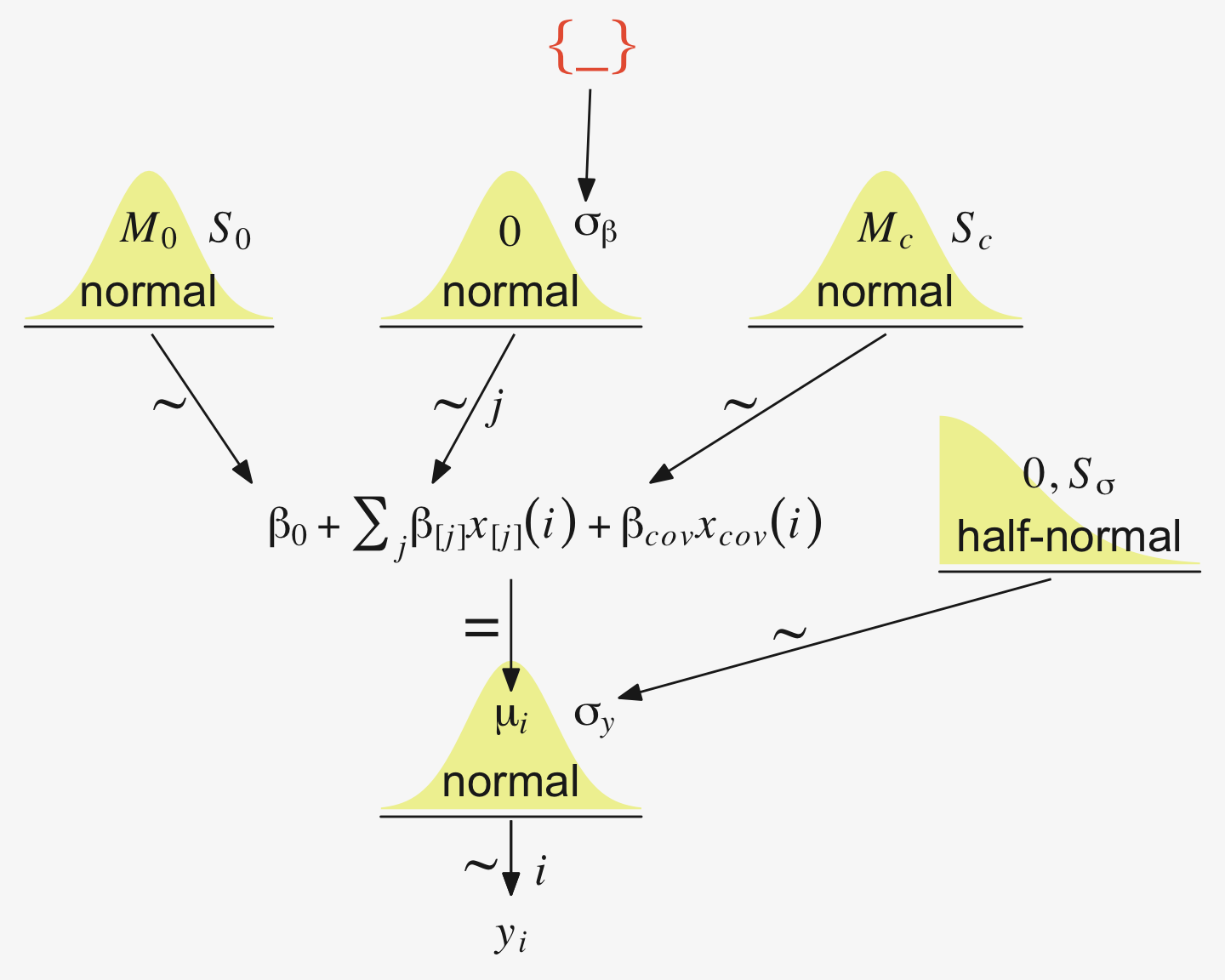

“Our goal is to estimate its parameters in a Bayesian framework. Therefore, all the parameters need to be given a meaningfully structured prior distribution” (p. 557). However, our approach will depart a little from the one in the text. All our parameters will not “have generic noncommittal prior distributions” (p. 557). Most importantly, we will not follow the example in (Gelman, 2006) of putting a broad uniform prior on \(\sigma_y\). Rather, we will continue using the half-Gaussian prior, as recommended by the Stan team. However, we will follow Kruschke’s lead for the overall intercept and use a Gaussian prior “made broad on the scale of the data” (p. 557). And like Kruschke, we will estimate \(\sigma_\beta\) from the data. To further get a sense of this, let’s make our version of the hierarchical model diagram of Figure 19.2.

# Bracket

p1 <- tibble(x = 0.99,

y = 0.5,

label = "{_}") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[8], family = "Times", hjust = 1, size = 10) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0), limits = c(0, 1)) +

ylim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

## Plain arrow

# Save our custom arrow settings

my_arrow <- arrow(angle = 20, length = unit(0.35, "cm"), type = "closed")

p2 <- tibble(x = 0.72,

y = 1,

xend = 0.68,

yend = 0.25) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, xend = xend,

y = y, yend = yend)) +

geom_segment(arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Normal density

p3 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.45), y = 0.6,

hjust = c(0.5, 0),

label = c("italic(M)[0]", "italic(S)[0]"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Second normal density

p4 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.45), y = 0.6,

hjust = c(0.5, 0),

label = c("0", "sigma[beta]"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Two annotated arrows

p5 <- tibble(x = c(0.16, 0.81),

y = 1,

xend = c(0.47, 0.77),

yend = 0) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, xend = xend,

y = y, yend = yend)) +

geom_segment(arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0.25, 0.74, 0.83), y = 0.5,

label = c("'~'", "'~'", "italic(j)"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = c(10, 10, 7)) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Likelihood formula

p6 <- tibble(x = 0.99,

y = 0.25,

label = "beta[0]+sum()[italic(j)]*beta['['*italic(j)*']']*italic(x)['['*italic(j)*']'](italic(i))") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", hjust = 1, parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0), limits = c(0, 1)) +

ylim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Half-normal density

p7 <- tibble(x = seq(from = 0, to = 3, by = 0.01)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.2,

label = "half-normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.6,

label = "0*','*~italic(S)[sigma]",

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Annotated arrow

p8 <- tibble(x = 0.38,

y = 0.65,

label = "'='") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 10) +

geom_segment(x = 0.5, xend = 0.5,

y = 1, yend = 0.25,

arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# The third normal density

p9 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.45), y = 0.6,

hjust = c(0.5, 0),

label = c("mu[italic(i)]", "sigma[italic(y)]"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Another annotated arrow

p10 <- tibble(x = 0.55,

y = 0.6,

label = "'~'") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 10) +

geom_segment(x = 0.82, xend = 0.38,

y = 1, yend = 0.2,

arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# The final annotated arrow

p11 <- tibble(x = c(0.375, 0.625),

y = c(1/3, 1/3),

label = c("'~'", "italic(i)")) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(size = c(10, 7),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE) +

geom_segment(x = 0.5, xend = 0.5,

y = 1, yend = 0,

arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Some text

p12 <- tibble(x = 0.5,

y = 0.5,

label = "italic(y[i])") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Define the layout

layout <- c(

area(t = 1, b = 1, l = 6, r = 7),

area(t = 2, b = 3, l = 6, r = 7),

area(t = 3, b = 4, l = 1, r = 3),

area(t = 3, b = 4, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 6, b = 7, l = 1, r = 7),

area(t = 5, b = 6, l = 1, r = 7),

area(t = 6, b = 7, l = 9, r = 11),

area(t = 9, b = 10, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 8, b = 9, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 8, b = 9, l = 5, r = 11),

area(t = 11, b = 11, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 12, b = 12, l = 5, r = 7))

# Combine, adjust, and display

(p1 + p2 + p3 + p4 + p6 + p5 + p7 + p9 + p8 + p10 + p11 + p12) +

plot_layout(design = layout) &

ylim(0, 1) &

theme(plot.margin = margin(0, 5.5, 0, 5.5))

Later on in the text, Kruschke opined:

A crucial pre-requisite for estimating \(\sigma_\beta\) from all the groups is an assumption that all the groups are representative and informative for the estimate. It only makes sense to influence the estimate of one group with data from the other groups if the groups can be meaningfully described as representative of a shared higher-level distribution. (p. 559)

Although I agree with him in spirit, this doesn’t appear to strictly be the case. As odd and paradoxical as this sounds, partial pooling can be of use even when the some of the cases are of a different kind. For more on the topic, see Efron and Morris’s classic (1977) paper, Stein’s paradox in statistics, and my blog post walking out one of their examples in brms.

19.3.1 Implementation in JAGS brms

The brms setup, of course, differs a bit from JAGS.

fit <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = gaussian,

y ~ 1 + (1 | categirical_variable),

prior = c(prior(normal(0, <scale>), class = Intercept),

prior(normal(0, <scale>), class = b),

prior(cauchy(0, <scale>), class = sd),

prior(cauchy(0, <scale>), class = sigma)))The noise standard deviation \(\sigma_y\) is depicted in the prior statement including the argument class = sigma. The grand mean is depicted by the first 1 in the model formula and its prior is indicated by the class = Intercept argument. We indicate we’d like group-based deviations from the grand mean with the (1 | categirical_variable) syntax, where the 1 on the left side of the bar indicates we’d like our intercepts to vary by group and the categirical_variable part simply represents the name of a given categorical variable we’d like those intercepts to vary by. The brms default is to do this with deviance scores, the mean for which will be zero. Although it’s not obvious in the formula syntax, the model presumes the group-based deviations are normally distributed with a mean of zero and a standard deviation, which Kruschke termed \(\sigma_\beta\). There is no prior for the mean. It’s set at zero. But there is a prior for \(\sigma_\beta\), which is denoted by the argument class = sd. We, of course, are not using a uniform prior on any of our variance parameters. But in order to be weakly informative, we will use the half-Cauchy. Recall that since the brms default is to set the lower bound for any variance parameter to 0, there’s no need to worry about doing so ourselves. So even though the syntax only indicates cauchy, it’s understood to mean Cauchy with a lower bound at zero; since the mean is usually 0, that makes is a half-Cauchy.

Kruschke set the upper bound for his \(\sigma_y\) to 10 times the standard deviation of the criterion variable. The tails of the half-Cauchy are sufficiently fat that, in practice, I’ve found it doesn’t matter much what you set the \(\textit{SD}\) of its prior to. One is often a sensible default for reasonably-scaled data. But if we want to take a more principled approach, we can set it to the size of the criterion’s \(\textit{SD}\) or perhaps even 10 times that value.

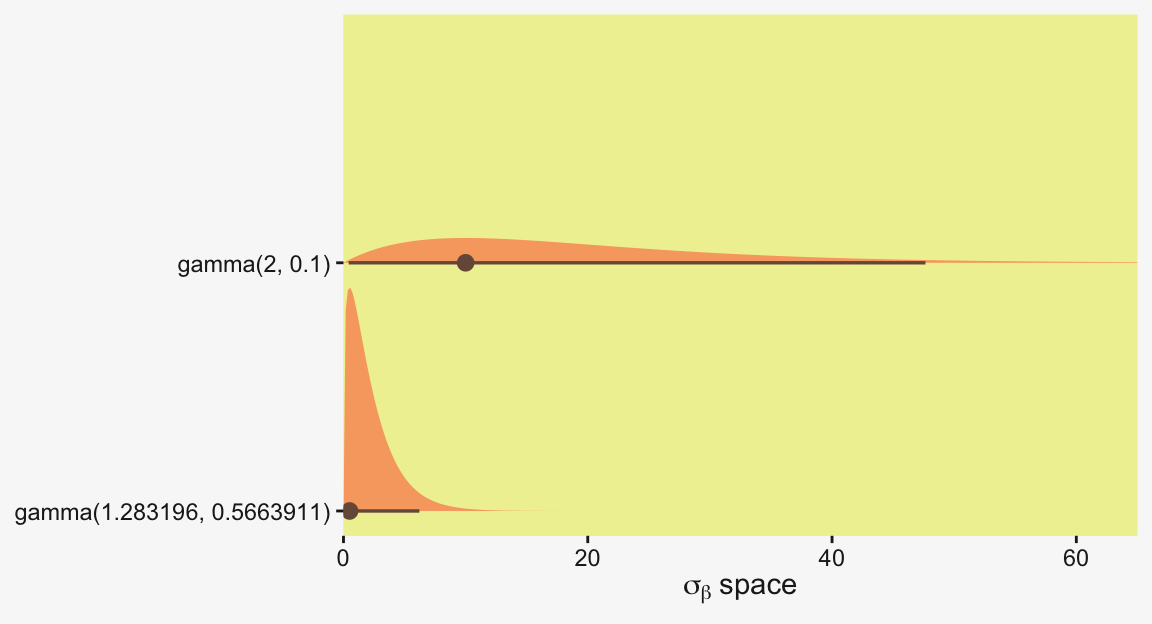

Kruschke suggested using a gamma on \(\sigma_\beta\), which is a sensible alternative to half-Cauchy often used within the Stan universe. Especially in situations in which you would like to (a) keep the variance parameter above zero, but (b) still allow it to be arbitrarily close to zero, and also (c) let the likelihood dominate the posterior, the Stan team recommends the \(\operatorname{Gamma}(2, 0)\) prior, based on the paper by Chung and colleagues (2013, click here). But you should note that I don’t mean a literal 0 for the second parameter in the gamma distribution, but rather some small value like 0.1 or so. This is all clarified in Chung et al. (2013).

If you’d like that prior be even less informative, just reduce it to like \(\operatorname{Gamma}(2, 0.01)\) or so. Kruschke went further to recommend “the shape and rate parameters of the gamma distribution are set so its mode is sd(y)/2 and its standard deviation is 2*sd(y), using the function gammaShRaFromModeSD explained in Section 9.2.2.” (pp. 560–561). Let’s make that function.

gamma_a_b_from_omega_sigma <- function(mode, sd) {

if (mode <= 0) stop("`mode` must be > 0")

if (sd <= 0) stop("`sd` must be > 0")

rate <- (mode + sqrt(mode^2 + 4 * sd^2)) / (2 * sd^2)

shape <- 1 + mode * rate

list(shape = shape, rate = rate)

}So in the case of standardized data where sd(1) = 1, we’d use our gamma_a_b_from_omega_sigma() function like so.

sd_y <- 1

omega <- sd_y / 2

sigma <- 2 * sd_y

(s_r <- gamma_a_b_from_omega_sigma(mode = omega, sd = sigma))$shape

[1] 1.283196

$rate

[1] 0.5663911We might compare Kruschke’s prior to the one recommended by Chung et al in a plot.

c(prior(gamma(2, 0.1)), # Chung et al (2013)

prior(gamma(1.283196, 0.5663911))) |> # Kruschke

parse_dist() |>

ggplot(aes(y = prior, xdist = .dist_obj)) +

stat_halfeye(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[1], fill = pp[10], linewidth = 1) +

scale_x_continuous(expression(sigma[beta]~space), expand = c(0, 0)) +

scale_y_discrete(NULL, expand = expansion(mult = 0.1)) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 65))

In the parameter space that matters, from zero to one, both of those gamma priors would be pretty noninformative. Computationally, both would keep the posteriors off the zero boundary, and their gentle right tails would keep the MCMC chains from spending a lot of time in ridiculous parts of the parameter space. I.e., when working with finite numbers of iterations, we want our MCMC chains wasting exactly zero iterations investigating what the density might be for \(\sigma_\beta \approx 1e10\) for standardized data.

19.3.2 Example: Sex and death

Let’s load and glimpse() at Hanley and Shapiro’s (1994) fruit-fly data.

my_data <- read_csv("data.R/FruitflyDataReduced.csv")

glimpse(my_data)Rows: 125

Columns: 3

$ Longevity <dbl> 35, 37, 49, 46, 63, 39, 46, 56, 63, 65, 56, 65, 70, 63, 65, 70, 77, 81, 86, 70, 70, 77, 77, 81, 77, 40, …

$ CompanionNumber <chr> "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", …

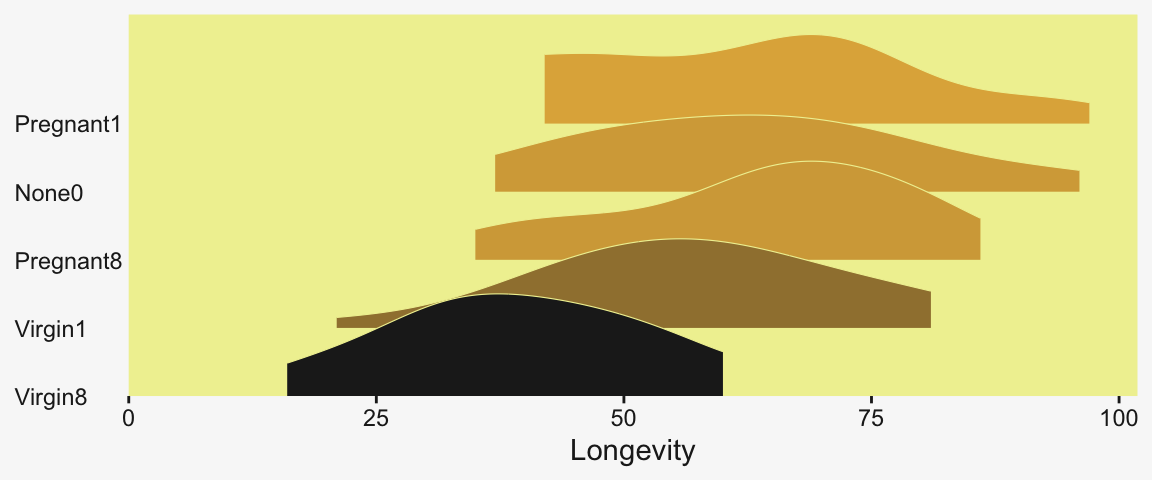

$ Thorax <dbl> 0.64, 0.68, 0.68, 0.72, 0.72, 0.76, 0.76, 0.76, 0.76, 0.76, 0.80, 0.80, 0.80, 0.84, 0.84, 0.84, 0.84, 0.…We can use stat_slab() to help get a sense of how our criterion Longevity is distributed across groups of CompanionNumber.

my_data |>

group_by(CompanionNumber) |>

mutate(group_mean = mean(Longevity)) |>

ungroup() |>

mutate(CompanionNumber = fct_reorder(CompanionNumber, group_mean)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = Longevity, y = CompanionNumber, fill = group_mean)) +

stat_slab(color = pp[9], linewidth = 0.2, scale = 3/2) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05)), limits = c(0, NA)) +

scale_y_discrete(NULL, expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.4))) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = pp[4], high = pp[2], breaks = NULL) +

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(hjust = 0),

axis.ticks.y = element_blank())

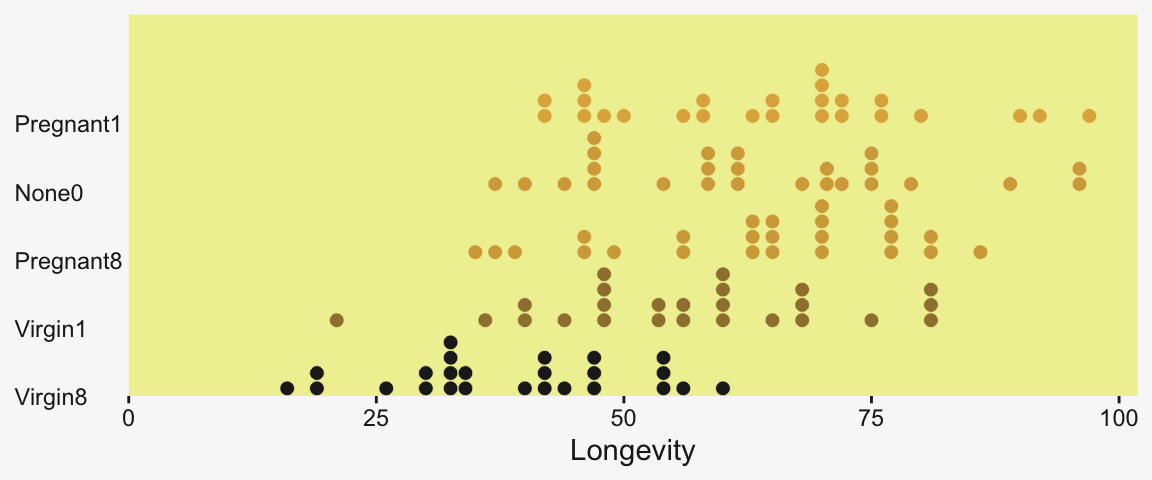

As an alternative, stat_dots() can also be fun with a plot like this.

my_data |>

group_by(CompanionNumber) |>

mutate(group_mean = mean(Longevity)) |>

ungroup() |>

mutate(CompanionNumber = fct_reorder(CompanionNumber, group_mean)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = Longevity, y = CompanionNumber, fill = group_mean)) +

stat_dots(color = pp[9], linewidth = 0.2) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05)), limits = c(0, NA)) +

scale_y_discrete(NULL, expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.4))) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = pp[4], high = pp[2], breaks = NULL) +

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(hjust = 0),

axis.ticks.y = element_blank())

We’ll want to do the preparatory work to define our stanvars.

(mean_y <- mean(my_data$Longevity))[1] 57.44(sd_y <- sd(my_data$Longevity))[1] 17.56389omega <- sd_y / 2

sigma <- 2 * sd_y

(s_r <- gamma_a_b_from_omega_sigma(mode = omega, sd = sigma))$shape

[1] 1.283196

$rate

[1] 0.03224747With the prep work is done, here are our stanvars.

stanvars <- stanvar(mean_y, name = "mean_y") +

stanvar(sd_y, name = "sd_y") +

stanvar(s_r$shape, name = "alpha") +

stanvar(s_r$rate, name = "beta")Now fit the model, our hierarchical Bayesian alternative to an ANOVA.

fit19.1 <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = gaussian,

Longevity ~ 1 + (1 | CompanionNumber),

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 5), class = Intercept),

prior(gamma(alpha, beta), class = sd),

prior(cauchy(0, sd_y), class = sigma)),

iter = 4000, warmup = 1000, chains = 4, cores = 4,

seed = 19,

control = list(adapt_delta = 0.995),

stanvars = stanvars,

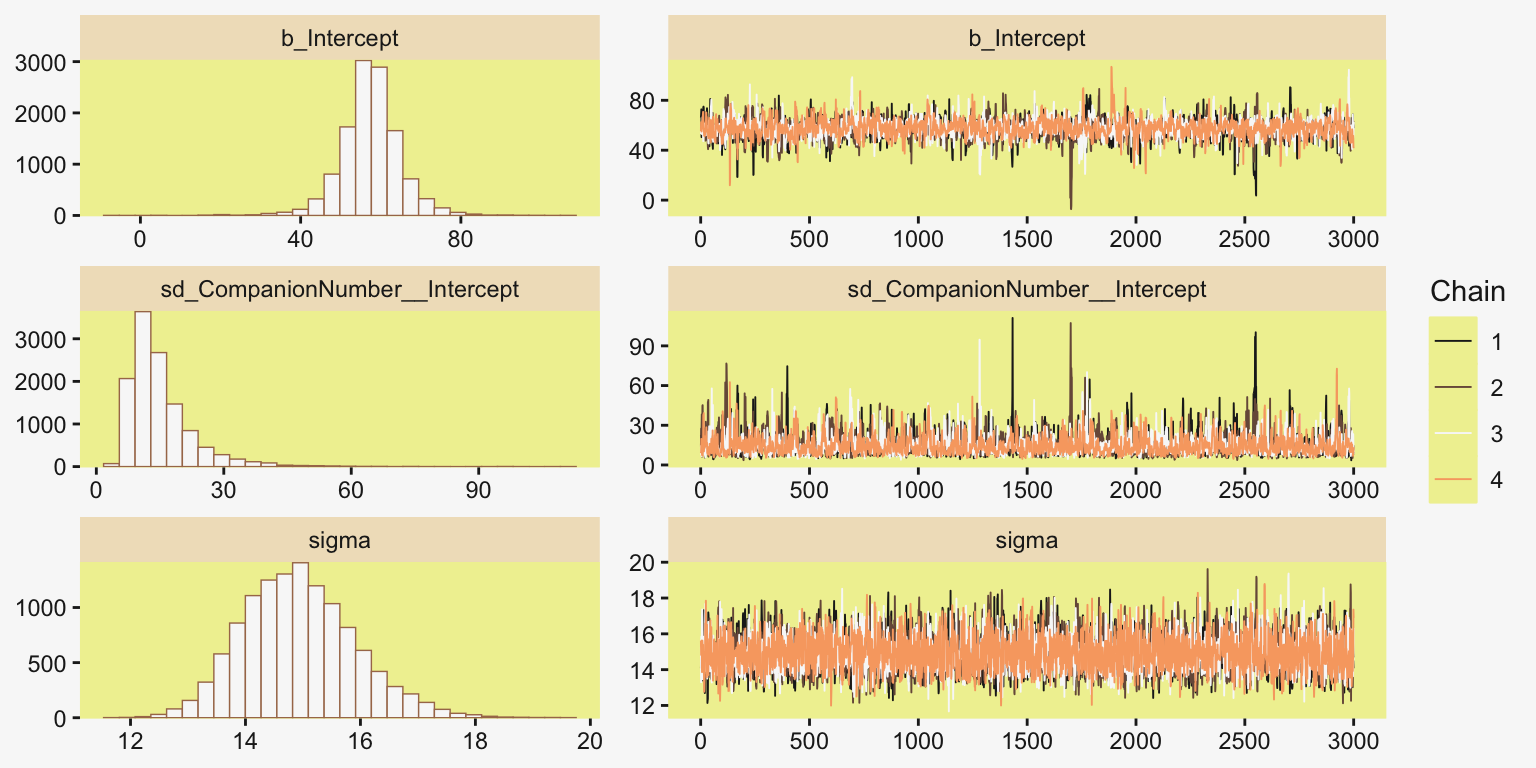

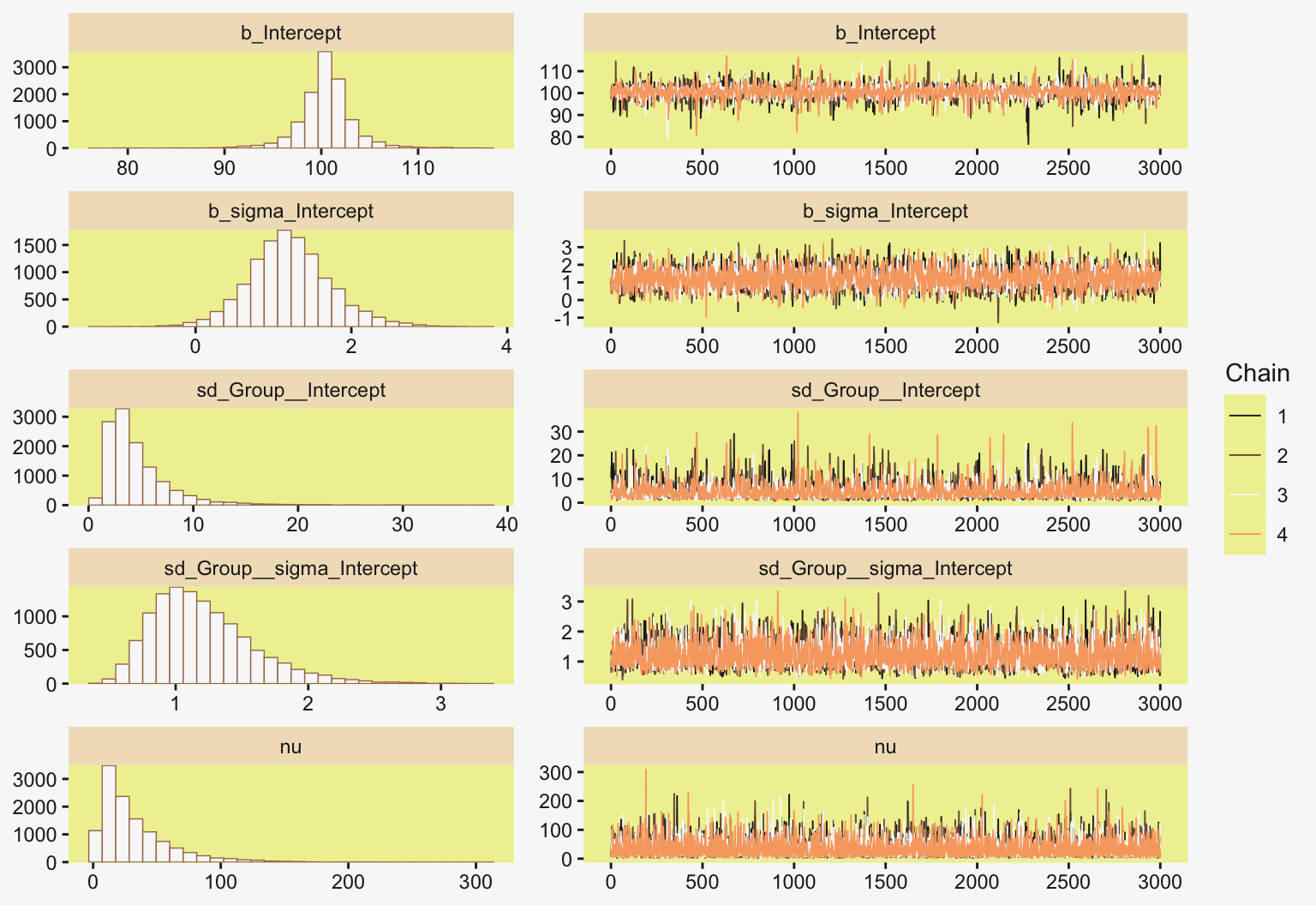

file = "fits/fit19.01")Much like Kruschke’s JAGS chains, our brms chains are well behaved, but only after fiddling with the adapt_delta setting.

color_scheme_set(scheme = pp[c(10, 8, 12, 5, 1, 4)])

plot(fit19.1, widths = c(2, 3))

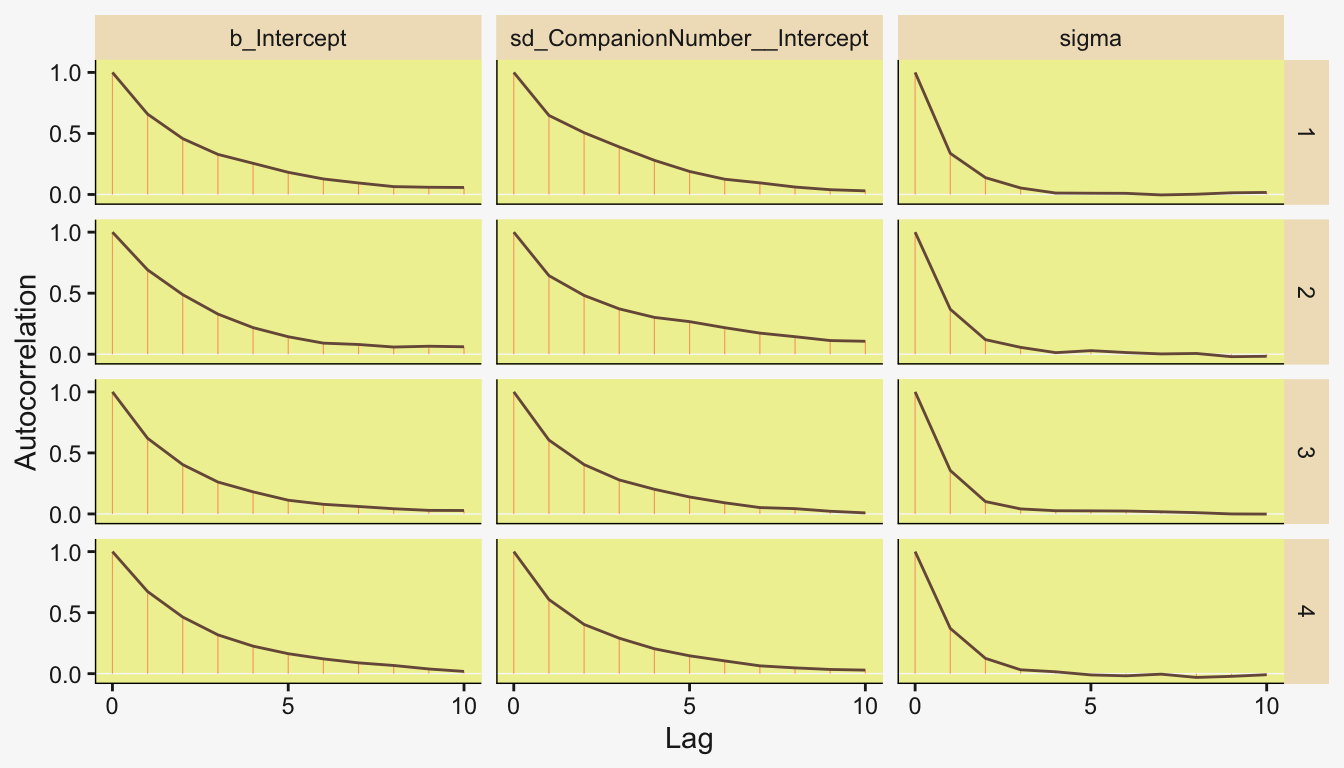

Also like Kruschke, our chains appear moderately autocorrelated.

# Extract the posterior draws

draws <- as_draws_df(fit19.1)

# Plot

draws |>

mutate(chain = .chain) |>

mcmc_acf(pars = vars(b_Intercept:sigma), lags = 10)

Here’s the model summary.

print(fit19.1) Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity

Formula: Longevity ~ 1 + (1 | CompanionNumber)

Data: my_data (Number of observations: 125)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 12000

Multilevel Hyperparameters:

~CompanionNumber (Number of levels: 5)

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sd(Intercept) 15.03 7.92 6.33 35.82 1.00 2249 3252

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 57.46 7.62 42.42 72.63 1.00 2381 2824

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 14.93 0.98 13.20 17.02 1.00 5792 5494

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).With the ranef() function, we can get the summaries of the group-specific deflections.

ranef(fit19.1)$CompanionNumber

, , Intercept

Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

None0 5.7612334 7.960761 -9.836995 22.065521

Pregnant1 6.9125893 7.965579 -8.466174 22.875082

Pregnant8 5.5780820 7.945730 -10.207332 21.718003

Virgin1 -0.6125707 7.929661 -16.261927 15.179777

Virgin8 -17.5589868 7.968122 -33.686386 -2.634376And with the coef() function, we can get those same group-level summaries in a non-deflection metric.

coef(fit19.1)$CompanionNumber

, , Intercept

Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

None0 63.22065 2.963166 57.46886 69.07916

Pregnant1 64.37201 2.945312 58.55072 70.15297

Pregnant8 63.03750 2.939493 57.13739 68.78137

Virgin1 56.84685 2.863651 51.27793 62.46548

Virgin8 39.90043 3.041876 33.80213 45.93965Those are all estimates of the group-specific means. Since it wasn’t modeled, all share a common \(\sigma_y\) posterior.

posterior_summary(fit19.1)["sigma", ] Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

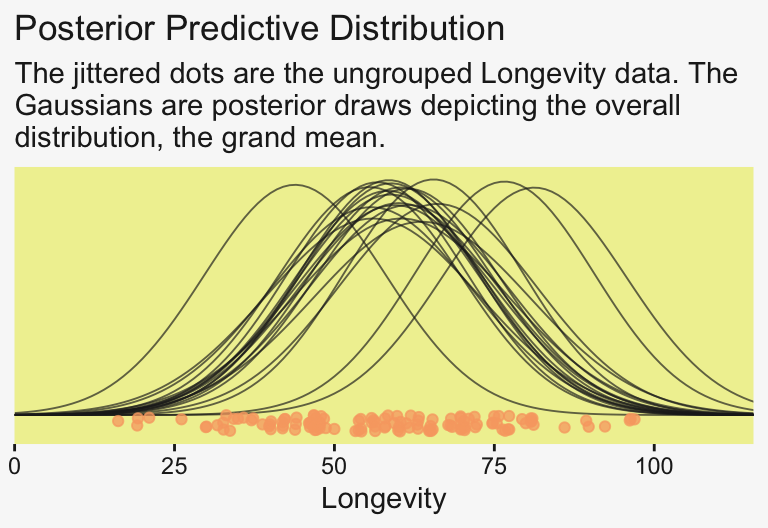

14.9299370 0.9776811 13.2044010 17.0232909 To prepare for our version of the top panel of Figure 19.3, let’s make a corresponding plot of the fixed intercept, the grand mean. For this plot, we’ll use slice_sample() to randomly sample from the posterior draws.

# How many random draws from the posterior would you like?

n_draws <- 20

# Subset

set.seed(19)

draws |>

slice_sample(n = n_draws, replace = FALSE) |>

expand_grid(Longevity = 0:120) |>

mutate(density = dnorm(x = Longevity, mean = b_Intercept, sd = sigma)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = Longevity)) +

geom_line(aes(y = density, group = .draw),

alpha = 2/3, color = pp[4], linewidth = 1/3) +

geom_jitter(data = my_data,

aes(y = -0.001),

alpha = 3/4, color = pp[10], height = 0.001) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 0:4 * 25, limits = c(0, NA),

expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

labs(title = "Posterior Predictive Distribution",

subtitle = "The jittered dots are the ungrouped Longevity data. The\nGaussians are posterior draws depicting the overall\ndistribution, the grand mean.") +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 110))

For the next plot, we’ll use a tidybayes::add_epred_draws()-based work flow instead.

densities <- my_data |>

distinct(CompanionNumber) |>

add_epred_draws(fit19.1, ndraws = n_draws, seed = 19, dpar = c("mu", "sigma"))

glimpse(densities)Rows: 100

Columns: 8

Groups: CompanionNumber, .row [5]

$ CompanionNumber <chr> "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", …

$ .row <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,…

$ .chain <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .iteration <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .draw <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11…

$ .epred <dbl> 60.98989, 63.52877, 65.20998, 63.20160, 59.04026, 59.11319, 55.11527, 65.46010, 66.03362, 63.13123, 62.1…

$ mu <dbl> 60.98989, 63.52877, 65.20998, 63.20160, 59.04026, 59.11319, 55.11527, 65.46010, 66.03362, 63.13123, 62.1…

$ sigma <dbl> 16.65716, 14.39283, 14.21772, 14.36234, 15.50326, 14.84507, 14.06252, 13.89299, 14.37961, 14.45609, 15.5…With the first two lines, we made a \(5 \times 1\) tibble containing the five levels of the experimental grouping variable, CompanionNumber. The add_epred_draws() function comes from tidybayes (see the Posterior fits section of Kay, 2021). The first argument of the add_epred_draws() is newdata, which works much like it does in brms::fitted(); it took our \(5 \times 1\) tibble. The next argument took our brms model fit, fit19.1. With the ndraws argument, we indicated we just wanted 20 random draws from the posterior. The seed argument makes those random draws reproducible. With dpar, we requested distributional regression parameters in the output. In our case, those were the \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) values for each level of CompanionNumber. Since we took 20 draws across 5 groups, we ended up with a 100-row tibble.

The next steps are a direct extension of the method we used to make our Gaussians for our version of Figure 19.1.

densities <- densities |>

mutate(ll = qnorm(0.025, mean = mu, sd = sigma),

ul = qnorm(0.975, mean = mu, sd = sigma)) |>

mutate(Longevity = map2(.x = ll, .y = ul,

.f = \(ll, ul) seq(from = ll, to = ul, length.out = 100))) |>

unnest(Longevity) |>

mutate(density = dnorm(Longevity, mu, sigma))

glimpse(densities)Rows: 10,000

Columns: 12

Groups: CompanionNumber, .row [5]

$ CompanionNumber <chr> "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", …

$ .row <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ .chain <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .iteration <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .draw <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ .epred <dbl> 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.9…

$ mu <dbl> 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.98989, 60.9…

$ sigma <dbl> 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.65716, 16.6…

$ ll <dbl> 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.34246, 28.3…

$ ul <dbl> 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.63732, 93.6…

$ Longevity <dbl> 28.34246, 29.00201, 29.66155, 30.32110, 30.98064, 31.64018, 32.29973, 32.95927, 33.61882, 34.27836, 34.9…

$ density <dbl> 0.003508706, 0.003788874, 0.004085002, 0.004397376, 0.004726222, 0.005071701, 0.005433909, 0.005812864, …If you look at the code we used to make ll and ul, you’ll see we used 95% intervals, this time. Our second mutate() function is basically the same. After unnesting the tibble, we just needed to plug in the Longevity, mu, and sigma values into the dnorm() function to compute the corresponding density values.

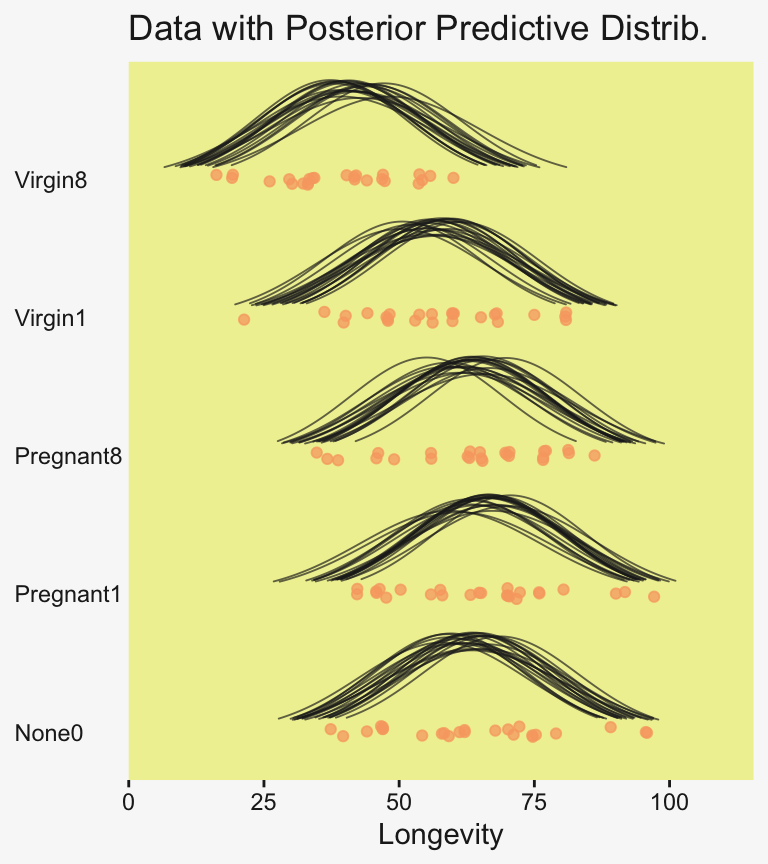

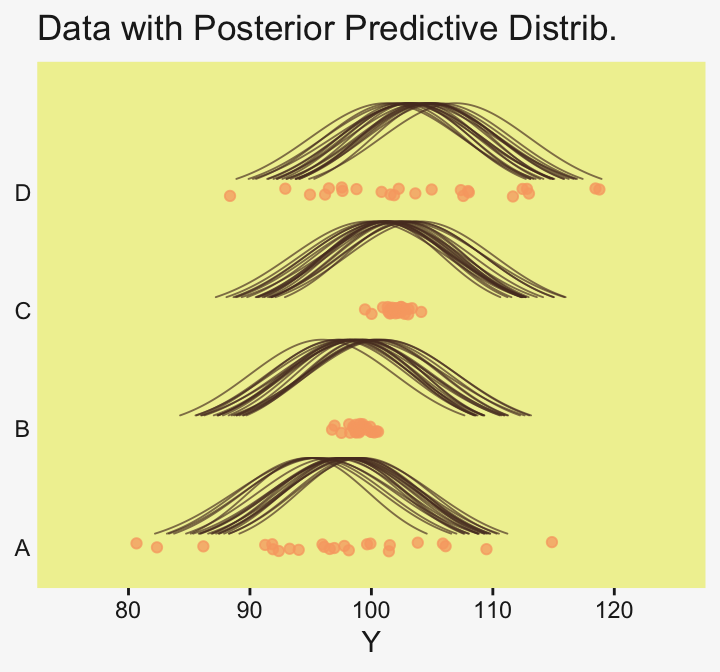

densities |>

ggplot(aes(x = Longevity, y = CompanionNumber)) +

# Here we make our density lines

geom_ridgeline(aes(height = density, group = interaction(CompanionNumber, .draw)),

color = adjustcolor(pp[4], alpha.f = 2/3), fill = NA,

linewidth = 1/3, scale = 25) +

# The original data with little jitter thrown in

geom_jitter(data = my_data,

alpha = 3/4, color = pp[10], height = 0.04) +

# Pretty much everything below this line is aesthetic fluff

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 0:4 * 25, limits = c(0, 110),

expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

labs(y = NULL,

title = "Data with Posterior Predictive Distrib.") +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(1.25, 5.25)) +

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(hjust = 0),

axis.ticks.y = element_blank())

Do be aware that when you use this method, you may have to fiddle around with the geom_ridgeline() scale argument to get the Gaussian’s heights on reasonable-looking relative heights. Stick in different numbers to get a sense of what I mean. I also find that I’m often not a fan of the way the spacing on the y axis ends up with default geom_ridgeline(). It’s easy to overcome this with a little ylim fiddling.

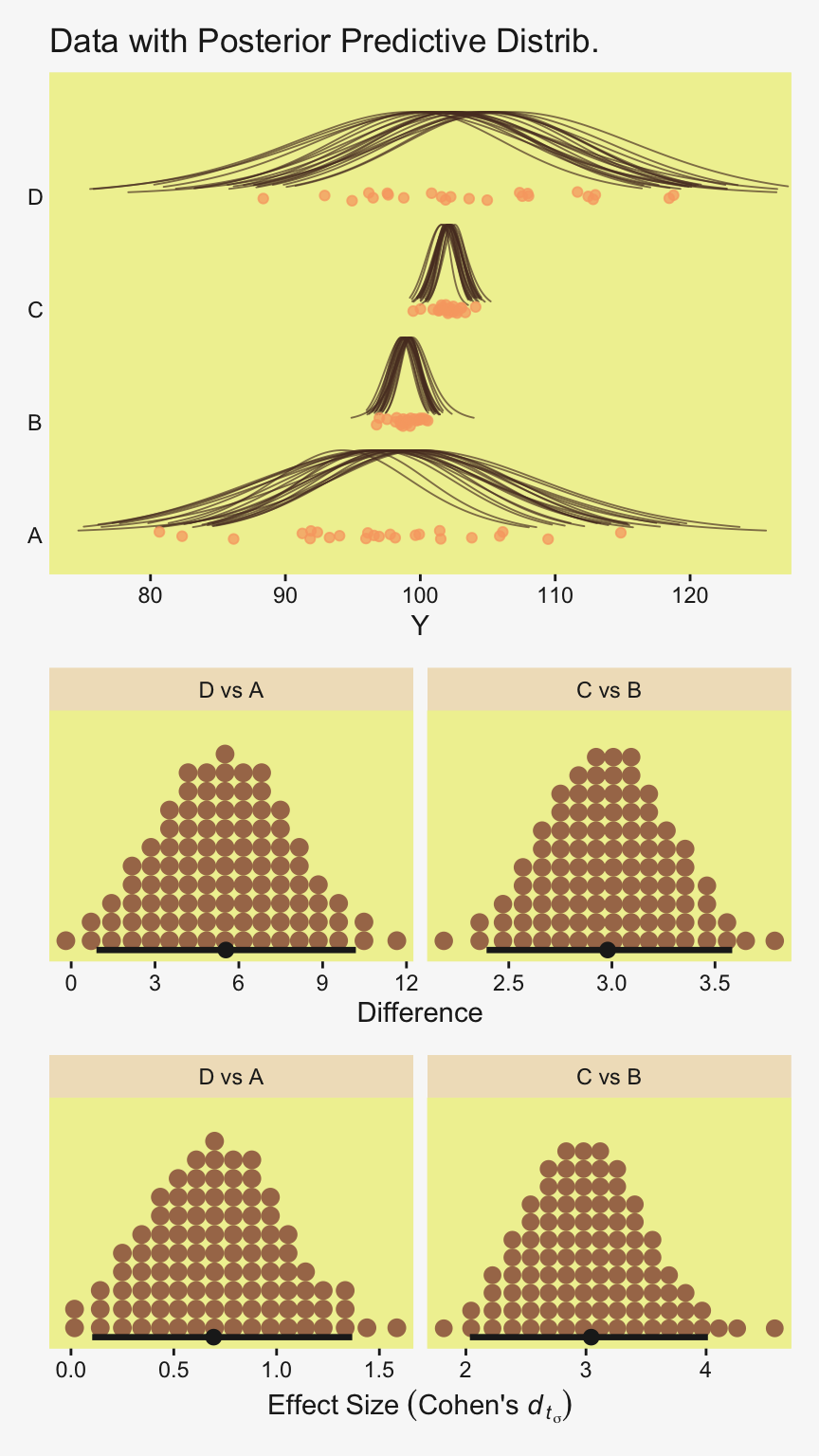

To return to the more substantive interpretation, the top panel of

Figure 19.3 suggests that the normal distributions with homogeneous variances appear to be reasonable descriptions of the data. There are no dramatic outliers relative to the posterior predicted curves, and the spread of the data within each group appears to be reasonably matched by the width of the posterior normal curves. (Be careful when making visual assessments of homogeneity of variance because the visual spread of the data depends on the sample size; for a reminder see the [see the right panel of Figure 17.1, p. 478].) The range of credible group means, indicated by the peaks of the normal curves, suggests that the group Virgin8 is clearly lower than the others, and the group Virgin1 might be lower than the controls. To find out for sure, we need to examine the differences of group means, which we do in the next section. (p. 564)

For clarity, the “see the right panel of Figure 17.1, p. 478” part was changed following Kruschke’s Corrigenda.

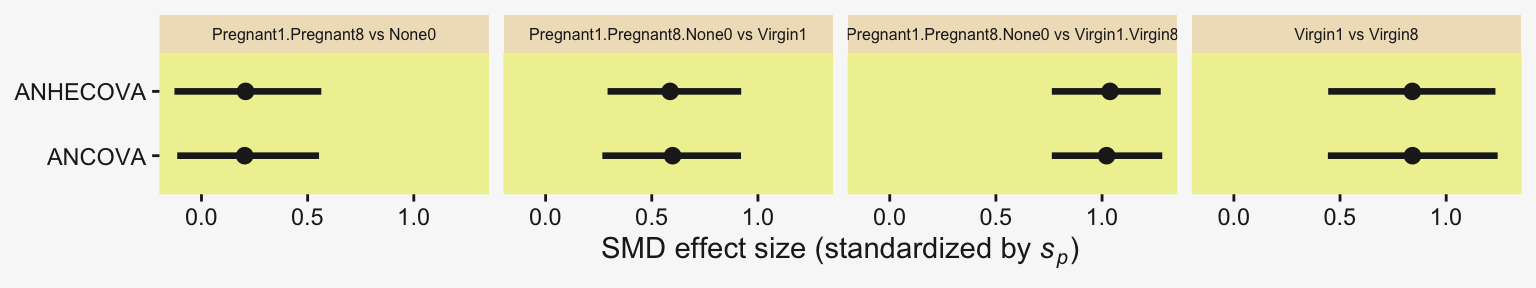

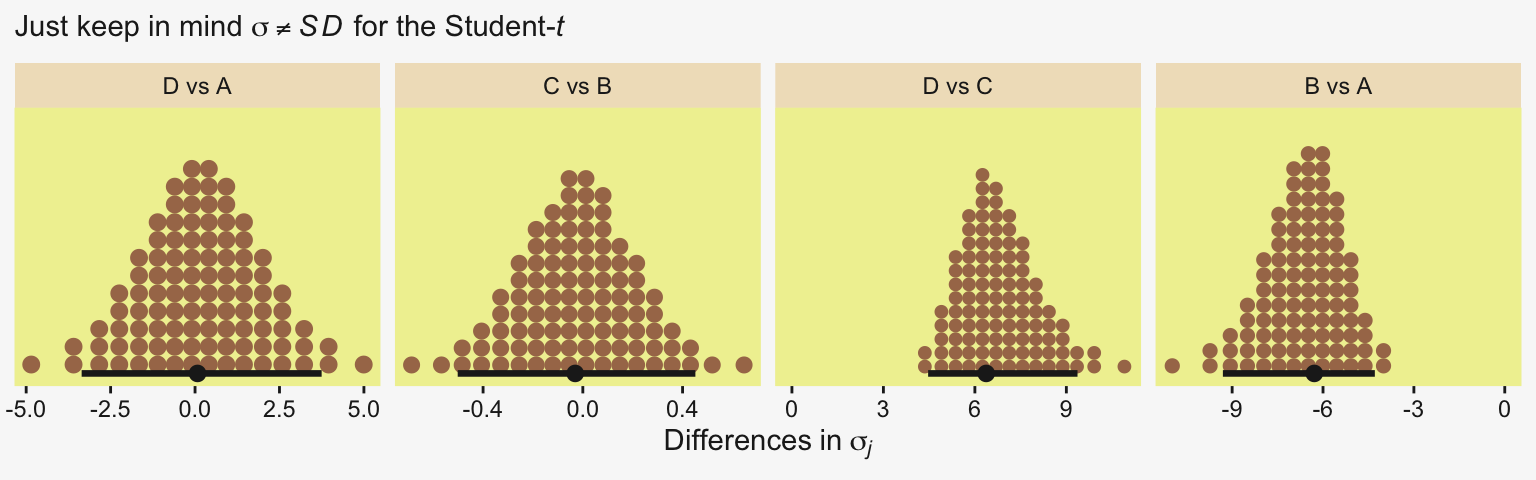

19.3.3 Contrasts

It is straight forward to examine the posterior distribution of credible differences. Every step in the MCMC chain provides a combination of group means that are jointly credible, given the data. Therefore, every step in the MCMC chain provides a credible difference between groups…

To construct the credible differences of group \(1\) and group \(2\), at every step in the MCMC chain we compute

\[\begin{align*} \mu_1 - \mu_2 & = (\beta_0 + \beta_1) - (\beta_0 + \beta_2) \\ & = (+1) \cdot \beta_1 + (-1) \cdot \beta_2 \end{align*}\]

In other words, the baseline cancels out of the calculation, and the difference is a sum of weighted group deflections. Notice that the weights sum to zero. To construct the credible differences of the average of groups \(1\)-\(3\) and the average of groups \(4\)-\(5\), at every step in the MCMC chain we compute

\[\begin{align*} \small{(\mu_1 + \mu_2 + \mu_3) / 3 - (\mu_4 + \mu_5) / 2} & = \small{((\beta_0 + \beta_1) + (\beta_0 + \beta_2) + (\beta_0 + \beta_3) ) / 3 - ((\beta_0 + \beta_4) + (\beta_0 + \beta_5) ) / 2} \\ & = \small{(\beta_1 + \beta_2 + \beta_3) / 3 - (\beta_4 + \beta_5) / 2} \\ & = \small{(+ 1/3) \cdot \beta_1 + (+ 1/3) \cdot \beta_2 + (+ 1/3) \cdot \beta_3 + (- 1/2) \cdot \beta_4 + (- 1/2) \cdot \beta_5} \end{align*}\]

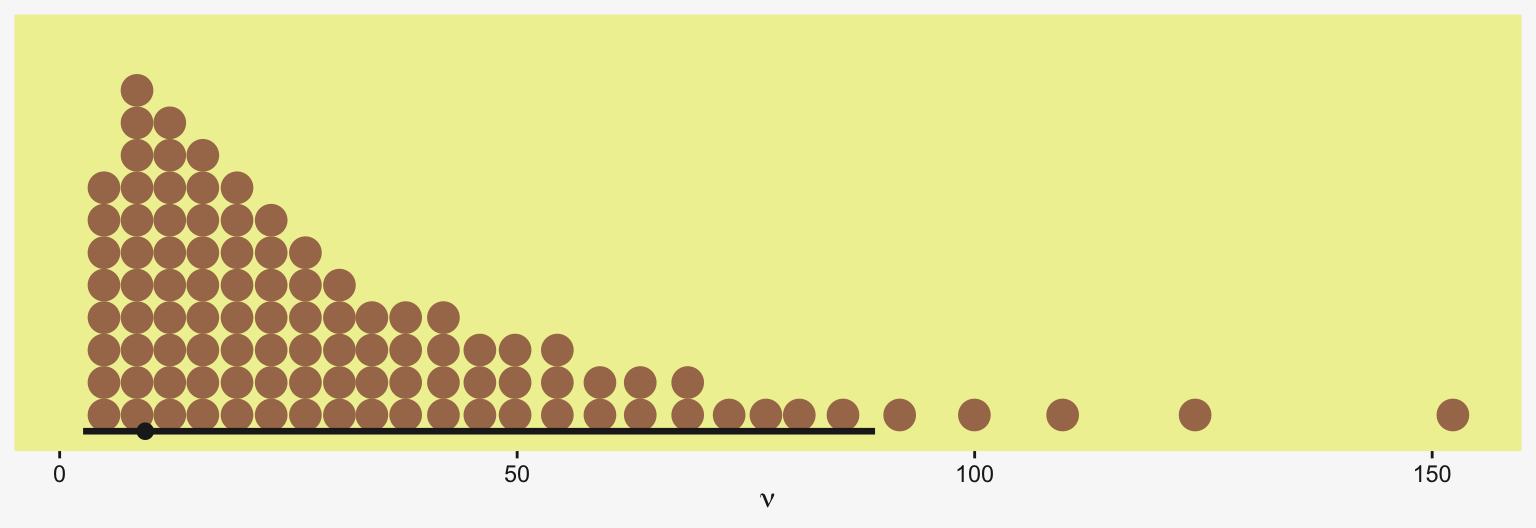

Again, the difference is a sum of weighted group deflections. The coefficients on the group deflections have the properties that they sum to zero, with the positive coefficients summing to \(+1\) and the negative coefficients summing to \(−1\). Such a combination is called a contrast. The differences can also be expressed in terms of effect size, by dividing the difference by \(\sigma_y\) at each step in the chain. (pp. 565–566)

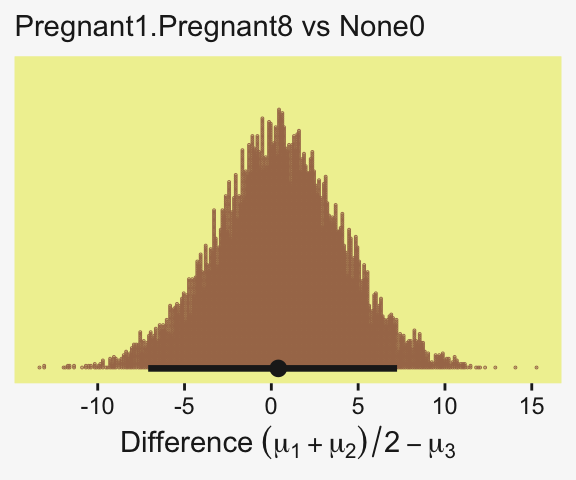

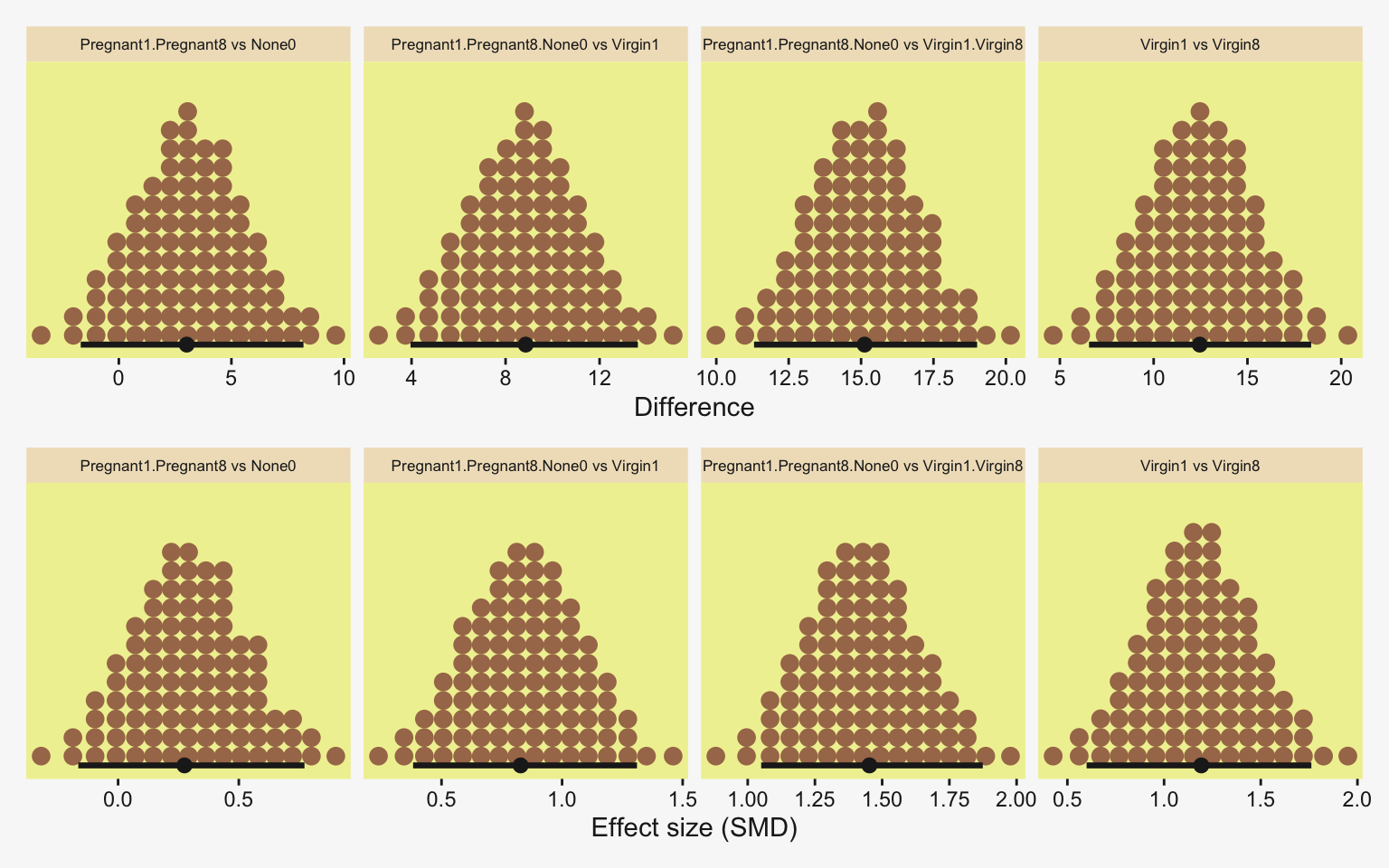

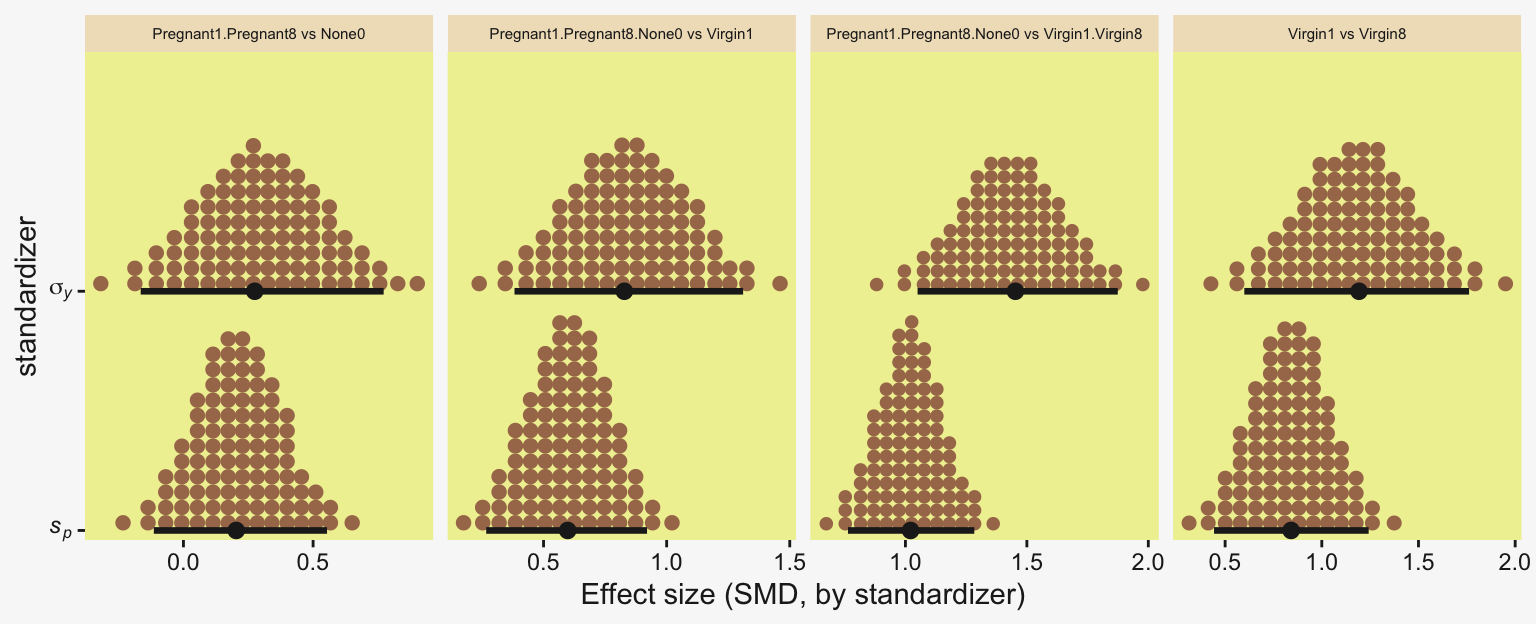

To warm up, here’s how to compute the first contrast shown in the lower portion of Kruschke’s Figure 19.3–the contrast between the two pregnant conditions and the none-control condition. In this code chunk, and the code chunks to follow, I’ll be renaming the draws columns on the fly so reduce the horizontal space.

draws |>

rename(p1 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant1,Intercept]`,

p8 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant8,Intercept]`,

n0 = `r_CompanionNumber[None0,Intercept]`) |>

mutate(contrast = (p1 + p8) / 2 - n0) |>

ggplot(aes(x = contrast)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], slab_color = pp[5], slab_fill = pp[5]) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

labs(x = expression(Difference~(mu[1]+mu[2])/2-mu[3]),

subtitle = "Pregnant1.Pregnant8 vs None0")

Up to this point, our primary mode of showing marginal posterior distributions has either been minute variations on Kruschke’s typical histogram approach or with densities. We’ll use those again in the future, too. In this chapter and the next, we’ll veer a little further from the source material and depict our marginal posteriors with dot plots and their very close relatives, quantile plots. In the dot plot, above, each of the 4,000 posterior draws is depicted by one of the stacked brown dots. To stack the dots in neat columns like that, tidybayes has to round a little. Though we lose something in the numeric precision, we gain a lot in interpretability. We’ll have more to say in just a moment.

In case you were curious, here are the HMC-based posterior mode and 95% HDIs.

draws |>

rename(p1 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant1,Intercept]`,

p8 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant8,Intercept]`,

n0 = `r_CompanionNumber[None0,Intercept]`) |>

mutate(contrast = (p1 + p8) / 2 - n0) |>

mode_hdi(contrast)# A tibble: 1 × 6

contrast .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

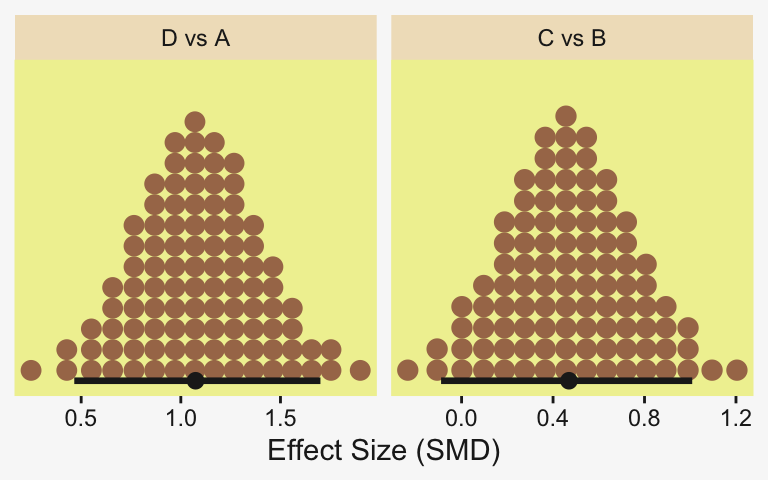

1 0.401 -7.09 7.24 0.95 mode hdi Little difference, there. Now let’s quantify the same contrast as a standardized mean difference (SMD) effect size.

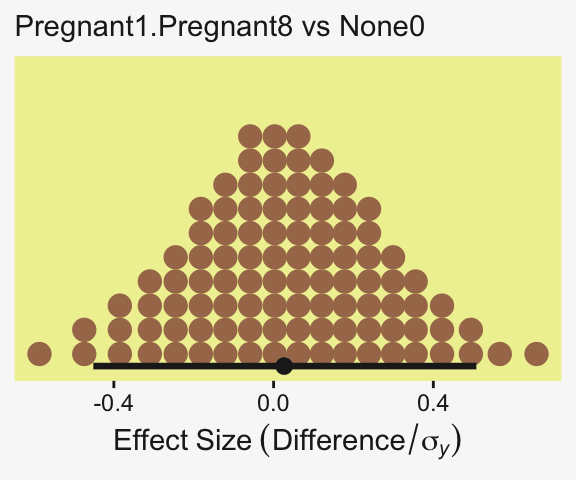

draws |>

rename(p1 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant1,Intercept]`,

p8 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant8,Intercept]`,

n0 = `r_CompanionNumber[None0,Intercept]`) |>

mutate(es = ((p1 + p8) / 2 - n0) / sigma) |>

ggplot(aes(x = es)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

labs(x = expression(Effect~Size~(Difference/sigma[italic(y)])),

subtitle = "Pregnant1.Pregnant8 vs None0")

This SMD effect size is also effectively a form of a Cohen’s \(d\), which we discussed in detail in Chapter 16. In the context of this model, the \(\sigma_y\) posterior is effectively a model-based pooled standard deviation–it’s the standard deviation in the data after we have removed the variation in the group means.

We should also point out here that the non-standardized contrast we initially made above could also stand as the effect size, provided that that metric was meaningful to the target audience. But since I, for example, am not a fruit fly researcher, I find the Cohen’s \(d\) metric easier to understand. YMMV

Did you notice the quantiles = 100 argument within stat_dotsinterval()? Instead of a dot plot with 4,000 tiny little dots, that argument converted the output to a quantile plot. The 4,000 posterior draws are now summarized by 100 dots, each of which represents \(1\%\) of the total sample Fernandes et al. (2018). This quantile dot-plot method will be our main visualization approach for the rest of the chapter.

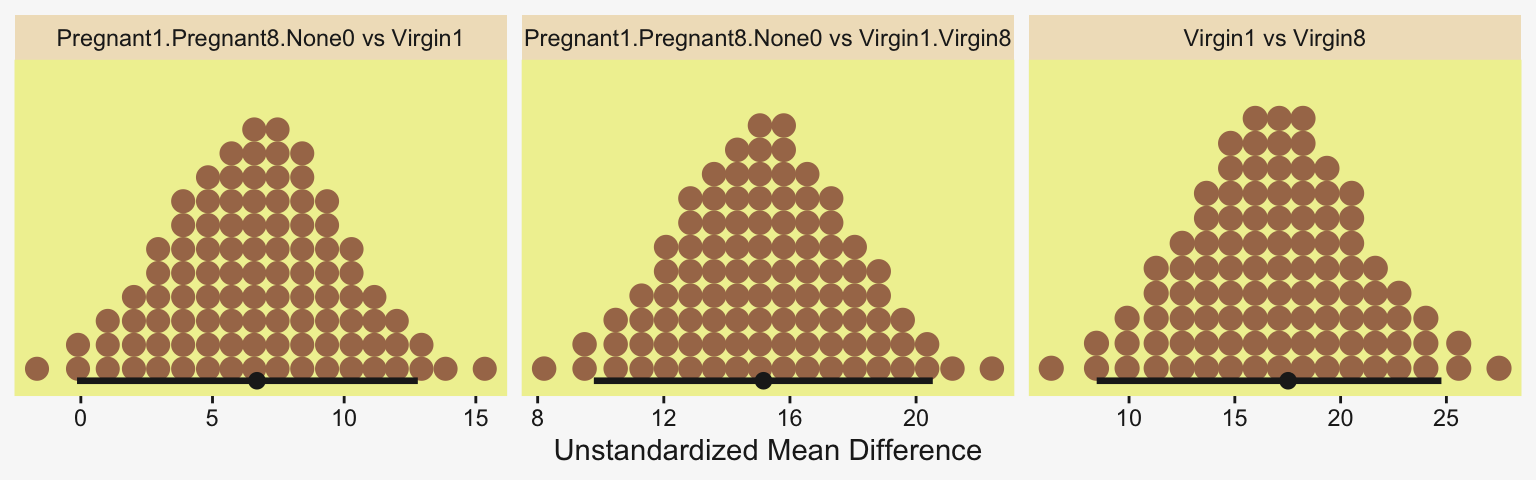

Okay, now let’s do the rest in bulk. First we’ll do the difference scores.

# Wrangle and save

differences <- draws |>

rename(n0 = `r_CompanionNumber[None0,Intercept]`,

p1 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant1,Intercept]`,

p8 = `r_CompanionNumber[Pregnant8,Intercept]`,

v1 = `r_CompanionNumber[Virgin1,Intercept]`,

v8 = `r_CompanionNumber[Virgin8,Intercept]`) |>

transmute(`Pregnant1.Pregnant8.None0 vs Virgin1` = (p1 + p8 + n0) / 3 - v1,

`Virgin1 vs Virgin8` = v1 - v8,

`Pregnant1.Pregnant8.None0 vs Virgin1.Virgin8` = ((p1 + p8 + n0) / 3) - ((v1 + v8) / 2))

# Plot

differences |>

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) |>

ggplot(aes(x = value)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab("Unstandardized Mean Difference") +

facet_wrap(~ name, scales = "free")

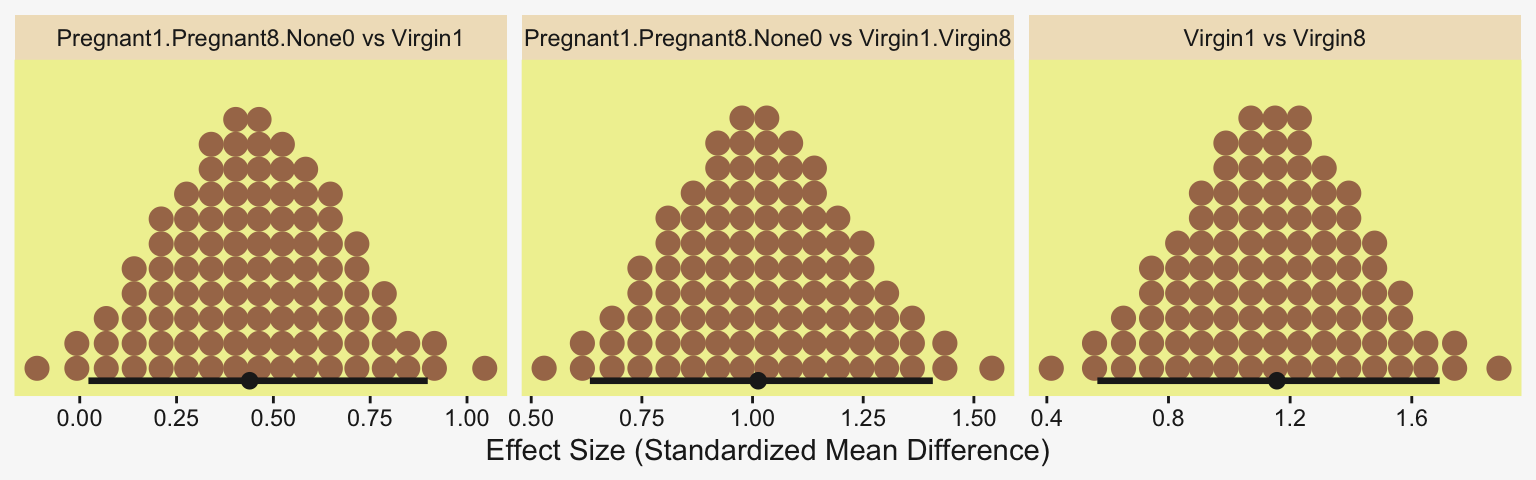

Because we save our data wrangling labor from above as differences, it won’t take much more effort to compute and plot the corresponding SMD effect sizes as displayed in the bottom row of Figure 19.3.

differences |>

mutate(across(.cols = everything(), .fns = \(x) x / draws$sigma)) |>

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) |>

ggplot(aes(x = value)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab("Effect Size (Standardized Mean Difference)") +

facet_wrap(~ name, scales = "free_x")

In traditional ANOVA, analysts often perform a so-called omnibus test that asks whether it is plausible that all the groups are simultaneously exactly equal. I find that the omnibus test is rarely meaningful, however…. In the hierarchical Bayesian estimation used here, there is no direct equivalent to an omnibus test in ANOVA, and the emphasis is on examining all the meaningful contrasts. (p. 567)

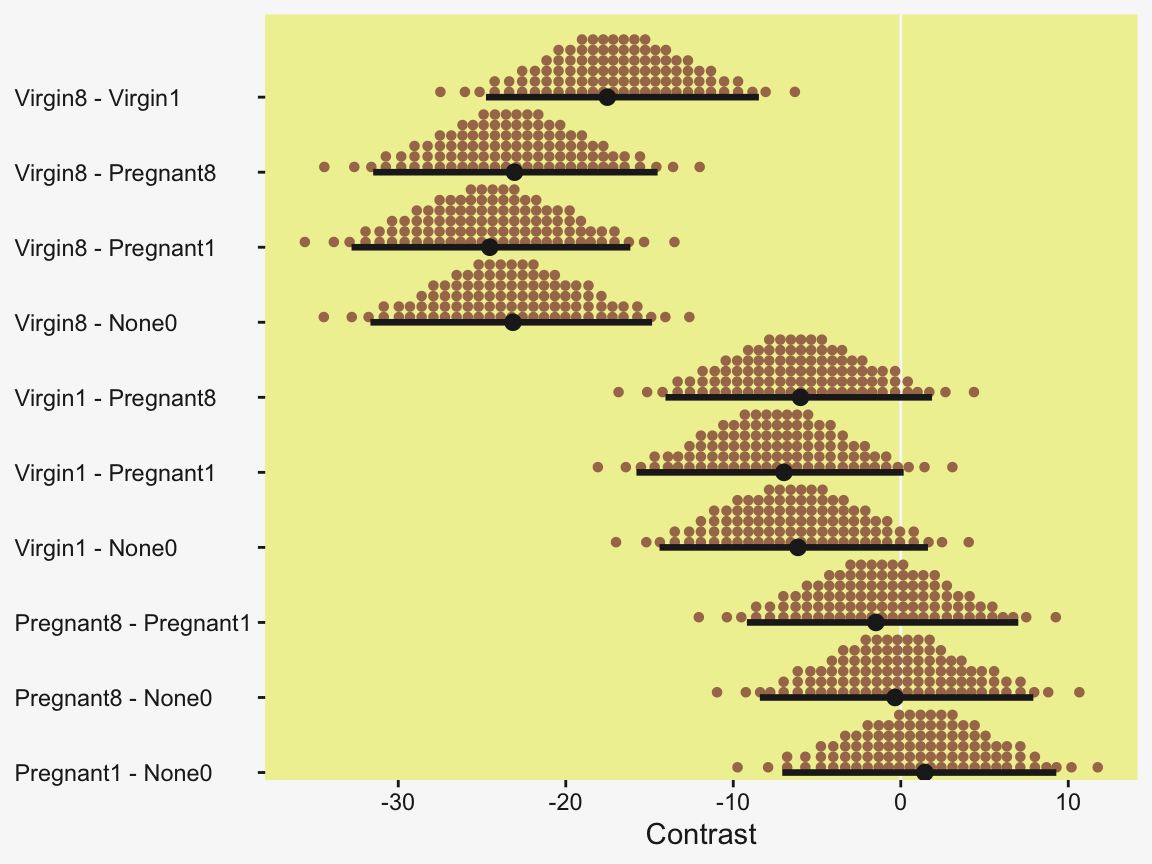

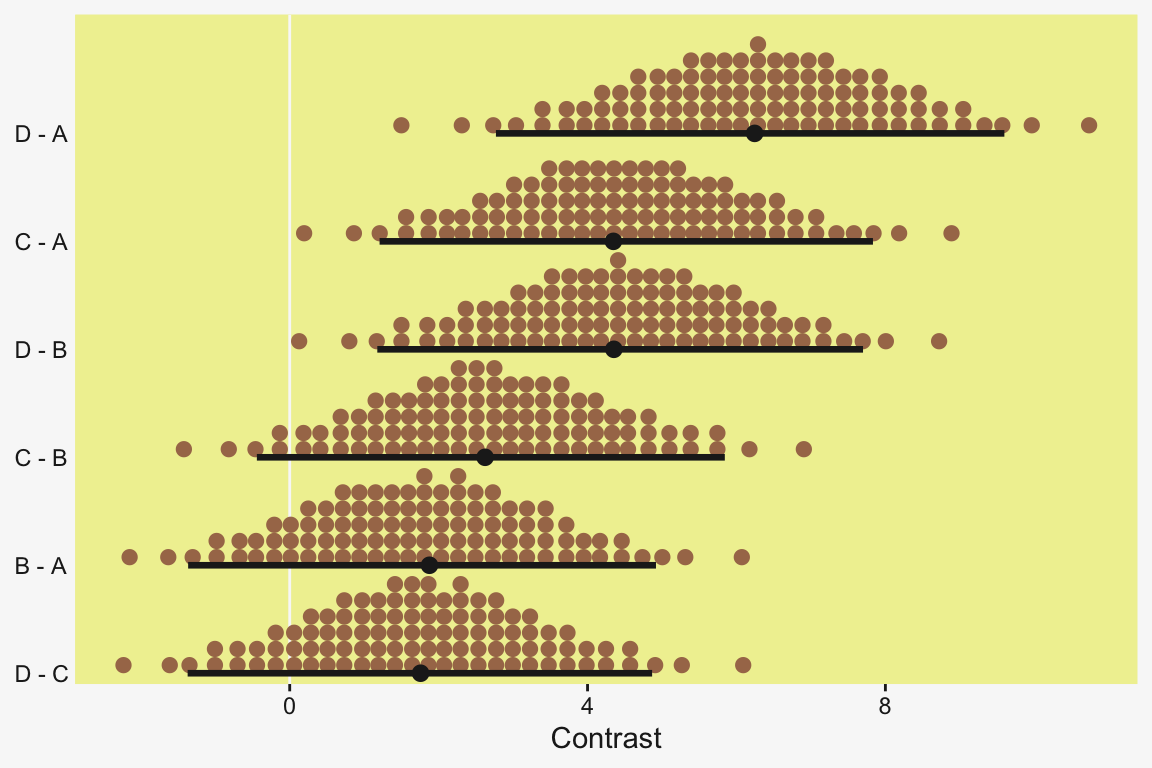

Speaking of all meaningful contrasts, if you’d like to make all pairwise comparisons in a hierarchical model of this form, tidybayes offers a convenient way to do so (see the Comparing levels of a factor section of Kay, 2021). Here we’ll demonstrate with stat_dotsinterval().

fit19.1 |>

# These two lines are where the magic is at

spread_draws(r_CompanionNumber[CompanionNumber, ]) |>

compare_levels(r_CompanionNumber, by = CompanionNumber) |>

ggplot(aes(x = r_CompanionNumber, y = CompanionNumber)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, color = pp[12]) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

labs(x = "Contrast",

y = NULL) +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(1.5, 10.5)) +

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(hjust = 0))

But back to that omnibus test notion. If you really wanted to, I suppose one rough analogue would be to use information criteria to compare the hierarchical model to one that includes a single intercept with no group-level deflections. Here’s what the simpler model would look like.

fit19.2 <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = gaussian,

Longevity ~ 1,

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 5), class = Intercept),

prior(cauchy(0, sd_y), class = sigma)),

iter = 4000, warmup = 1000, chains = 4, cores = 4,

seed = 19,

stanvars = stanvars,

file = "fits/fit19.02")Check the model summary.

print(fit19.2) Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity

Formula: Longevity ~ 1

Data: my_data (Number of observations: 125)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 12000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 57.42 1.59 54.30 60.52 1.00 10897 7658

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 17.67 1.12 15.63 20.02 1.00 10000 7461

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Here are their LOO values and their difference score.

fit19.1 <- add_criterion(fit19.1, criterion = "loo")

fit19.2 <- add_criterion(fit19.2, criterion = "loo")

loo_compare(fit19.1, fit19.2) |>

print(simplify = FALSE) elpd_diff se_diff elpd_loo se_elpd_loo p_loo se_p_loo looic se_looic

fit19.1 0.0 0.0 -517.7 6.9 5.5 0.6 1035.4 13.8

fit19.2 -19.3 5.3 -537.0 7.1 1.8 0.3 1074.0 14.2 The hierarchical model has a better LOO. Here are the stacking-based model weights.

(mw <- model_weights(fit19.1, fit19.2)) fit19.1 fit19.2

9.999989e-01 1.099269e-06 If you don’t like scientific notation, just round().

mw |>

round(digits = 3)fit19.1 fit19.2

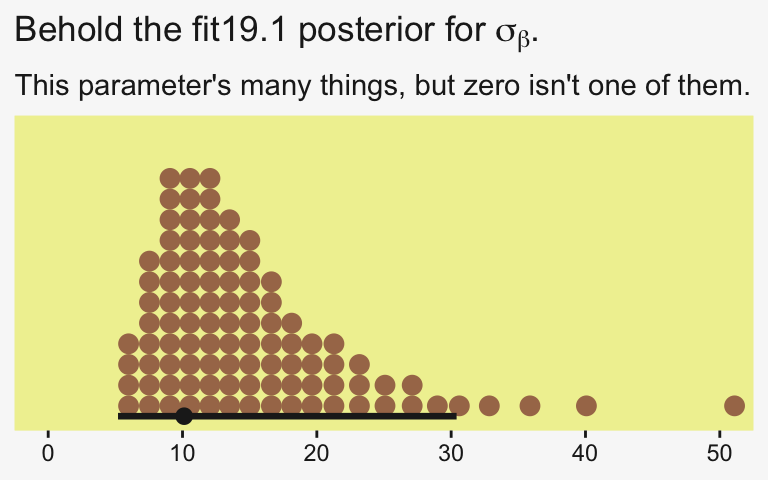

1 0 Yep, in complimenting the LOO difference, virtually all the stacking weight went to the hierarchical model. You might think of this another way. The conceptual question we’re asking is: Does it make sense to say that the \(\sigma_\beta\) parameter is zero? Is zero a credible value? We’ll, I suppose we could just look at the posterior to assess for that.

draws |>

ggplot(aes(x = sd_CompanionNumber__Intercept)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0, 50)) +

labs(x = NULL,

title = expression("Behold the fit19.1 posterior for "*sigma[beta]*"."),

subtitle = "This parameter's many things, but zero isn't one of them.")

Yeah, zero and other values close to zero don’t look credible for that parameter. 95% of the mass is between 5 and 30, with the bulk hovering around 10. We don’t need an \(F\)-test or even a LOO model comparison to see the writing on wall.

19.3.4 Multiple comparisons and shrinkage

The previous section suggested that an analyst should investigate all contrasts of interest. This recommendation can be thought to conflict with traditional advice in the context on null hypothesis significance testing, which instead recommends that a minimal number of comparisons should be conducted in order to maximize the power of each test while keeping the overall false alarm rate capped at 5% (or whatever maximum is desired)…. Instead, a Bayesian analysis can mitigate false alarms by incorporating prior knowledge into the model. In particular, hierarchical structure (which is an expression of prior knowledge) produces shrinkage of estimates, and shrinkage can help rein in estimates of spurious outlying data. For example, in the posterior distribution from the fruit fly data, the modal values of the posterior group means have a range of \(23.2\). The sample means of the groups have a range of \(26.1\). Thus, there is some shrinkage in the estimated means. The amount of shrinkage is dictated only by the data and by the prior structure, not by the intended tests. (p. 568)

We may as well compute those ranges by hand. Here’s the range of the observed data.

my_data |>

group_by(CompanionNumber) |>

summarise(mean = mean(Longevity)) |>

summarise(range = max(mean) - min(mean))# A tibble: 1 × 1

range

<dbl>

1 26.1For our hierarchical model fit19.1, the posterior means are rank ordered in the same way as the empirical data.

coef(fit19.1)$CompanionNumber[, , "Intercept"] |>

data.frame() |>

rownames_to_column(var = "companion_number") |>

arrange(Estimate) |>

mutate_if(is.double, .funs = round, digits = 1) companion_number Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

1 Virgin8 39.9 3.0 33.8 45.9

2 Virgin1 56.8 2.9 51.3 62.5

3 Pregnant8 63.0 2.9 57.1 68.8

4 None0 63.2 3.0 57.5 69.1

5 Pregnant1 64.4 2.9 58.6 70.2If we compute the range by a difference of the point estimates of the highest and lowest posterior means, we can get a quick number.

coef(fit19.1)$CompanionNumber[, , "Intercept"] |>

as_tibble() |>

summarise(range = max(Estimate) - min(Estimate))# A tibble: 1 × 1

range

<dbl>

1 24.5Note that wasn’t fully Bayesian of us. Those means and their difference carry uncertainty and that uncertainty can be fully expressed if we use all the posterior draws (i.e., use summary = FALSE and wrangle).

coef(fit19.1, summary = FALSE)$CompanionNumber[, , "Intercept"] |>

as_tibble() |>

transmute(range = Pregnant1 - Virgin8) |>

mode_hdi(range)# A tibble: 1 × 6

range .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 24.5 16.1 32.8 0.95 mode hdi Happily, the central tendency of the range is near equivalent with both methods, but now we have 95% intervals, too. Do note how wide they are. This is why we work with the full set of posterior draws.

19.3.5 The two-group case

A special case of our current scenario is when there are only two groups. The model of the present section could, in principle, be applied to the two-group case, but the hierarchical structure would do little good because there is virtually no shrinkage when there are so few groups (and the top-level prior on \(\sigma_\beta\) is broad as assumed here). (p. 568)

For kicks and giggles, let’s practice. Since Pregnant1 and Virgin8 had the highest and lowest empirical means—making them the groups best suited to define our range, we’ll use them to fit the 2-group hierarchical model. To fit it with haste, just use update().

fit19.3 <- update(

fit19.1,

newdata = my_data |>

filter(CompanionNumber %in% c("Pregnant1", "Virgin8")),

seed = 19,

file = "fits/fit19.03")Even with just two groups, there were no gross issues with fitting the model.

print(fit19.3) Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity

Formula: Longevity ~ 1 + (1 | CompanionNumber)

Data: filter(my_data, CompanionNumber %in% c("Pregnant1" (Number of observations: 50)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 12000

Multilevel Hyperparameters:

~CompanionNumber (Number of levels: 2)

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sd(Intercept) 32.95 22.22 8.95 94.60 1.00 2925 4477

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 51.11 25.09 -1.67 104.59 1.00 2830 2528

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 14.22 1.49 11.64 17.48 1.00 5671 4788

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).If you compare the posteriors for \(\sigma_\beta\) across the two models, you’ll see how the one for fit19.3 is substantially larger.

posterior_summary(fit19.1)["sd_CompanionNumber__Intercept", ] Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

15.033545 7.921127 6.328445 35.821608 posterior_summary(fit19.3)["sd_CompanionNumber__Intercept", ] Estimate Est.Error Q2.5 Q97.5

32.946365 22.223396 8.947535 94.604415 Here that is in a coefficient plot using tidybayes::stat_interval().

bind_rows(as_draws_df(fit19.1) |> select(sd_CompanionNumber__Intercept),

as_draws_df(fit19.3) |> select(sd_CompanionNumber__Intercept)) |>

mutate(fit = rep(c("fit19.1", "fit19.3"), each = n() / 2)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = sd_CompanionNumber__Intercept, y = fit)) +

stat_interval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = c(0.5, 0.8, 0.95)) +

scale_color_manual(values = pp[c(11, 5, 7)],

labels = c("95%", "80%", "50%")) +

scale_x_continuous(expression(sigma[beta]),

limits = c(0, NA), expand = expansion(mult = c(0, 0.05))) +

ylab(NULL) +

theme(legend.key.size = unit(0.45, "cm"))

This all implies less shrinkage and a larger range.

coef(fit19.3, summary = FALSE)$CompanionNumber[, , "Intercept"] |>

as_tibble() |>

transmute(range = Pregnant1 - Virgin8) |>

mode_hdi(range)# A tibble: 1 × 6

range .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 25.5 18.1 33.8 0.95 mode hdi And indeed, the range between the two groups is larger. Now the posterior mode for their difference has almost converged to that of the raw data. Kruschke then went on to recommend using a single-level model in such situations, instead.

That is why the two-group model in Section 16.3 did not use hierarchical structure, as illustrated in Figure 16.11 (p. 468). That model also used a \(t\) distribution to accommodate outliers in the data, and that model allowed for heterogeneous variances across groups. Thus, for two groups, it is more appropriate to use the model of Section 16.3. The hierarchical multi-group model is generalized to accommodate outliers and heterogeneous variances in Section 19.5. (p. 568)

As a refresher, here’s what the brms code for that Chapter 16 model looked like.

fit16.3 <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = student,

bf(Score ~ 0 + Group,

sigma ~ 0 + Group),

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 100), class = b),

prior(normal(0, log(sd_y)), class = b, dpar = sigma),

prior(exponential(one_over_twentynine), class = nu)),

chains = 4, cores = 4,

stanvars = stanvars,

seed = 16,

file = "fits/fit16.03")Let’s adjust it for our data. Since we have a reduced data set, we’ll need to re-compute our stanvars values, which were based on the raw data.

# It's easier to just make a reduced data set

my_small_data <- my_data |>

filter(CompanionNumber %in% c("Pregnant1", "Virgin8"))

(mean_y <- mean(my_small_data$Longevity))[1] 51.76(sd_y <- sd(my_small_data$Longevity))[1] 19.11145omega <- sd_y / 2

sigma <- 2 * sd_y

(s_r <- gamma_a_b_from_omega_sigma(mode = omega, sd = sigma))$shape

[1] 1.283196

$rate

[1] 0.02963623Here we update stanvars.

stanvars <- stanvar(mean_y, name = "mean_y") +

stanvar(sd_y, name = "sd_y") +

stanvar(s_r$shape, name = "alpha") +

stanvar(s_r$rate, name = "beta") +

stanvar(1/29, name = "one_over_twentynine")Note that our priors, here, are something of a blend of those from Chapter 16 and those from our hierarchical model, fit19.1.

fit19.4 <- brm(

data = my_small_data,

family = student,

bf(Longevity ~ 0 + CompanionNumber,

sigma ~ 0 + CompanionNumber),

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 10), class = b),

prior(normal(0, log(sd_y)), class = b, dpar = sigma),

prior(exponential(one_over_twentynine), class = nu)),

iter = 4000, warmup = 1000, chains = 4, cores = 4,

seed = 19,

stanvars = stanvars,

file = "fits/fit19.04")Here’s the model summary.

print(fit19.4) Family: student

Links: mu = identity; sigma = log

Formula: Longevity ~ 0 + CompanionNumber

sigma ~ 0 + CompanionNumber

Data: my_small_data (Number of observations: 50)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 12000

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

CompanionNumberPregnant1 64.63 3.27 58.00 70.96 1.00 13791 7956

CompanionNumberVirgin8 38.71 2.54 33.71 43.71 1.00 12375 7876

sigma_CompanionNumberPregnant1 2.73 0.15 2.44 3.04 1.00 12931 9309

sigma_CompanionNumberVirgin8 2.48 0.15 2.19 2.79 1.00 12608 8147

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

nu 39.59 30.91 5.80 120.30 1.00 12030 8145

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Man, look at those Bulk_ESS values! As it turns out, they can be greater than the number of post-warmup samples. And here’s the range in posterior means.

fixef(fit19.4, summary = FALSE) |>

as_tibble() |>

transmute(range = CompanionNumberPregnant1 - CompanionNumberVirgin8) |>

mode_hdi(range)# A tibble: 1 × 6

range .lower .upper .width .point .interval

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

1 25.8 17.7 33.8 0.95 mode hdi The results are pretty much the same as that of the two-group hierarchical model, maybe a touch larger. Yep, Kruschke was right: Hierarchical models with two groups and permissive priors on \(\sigma_\beta\) don’t shrink the estimates to the grand mean all that much.

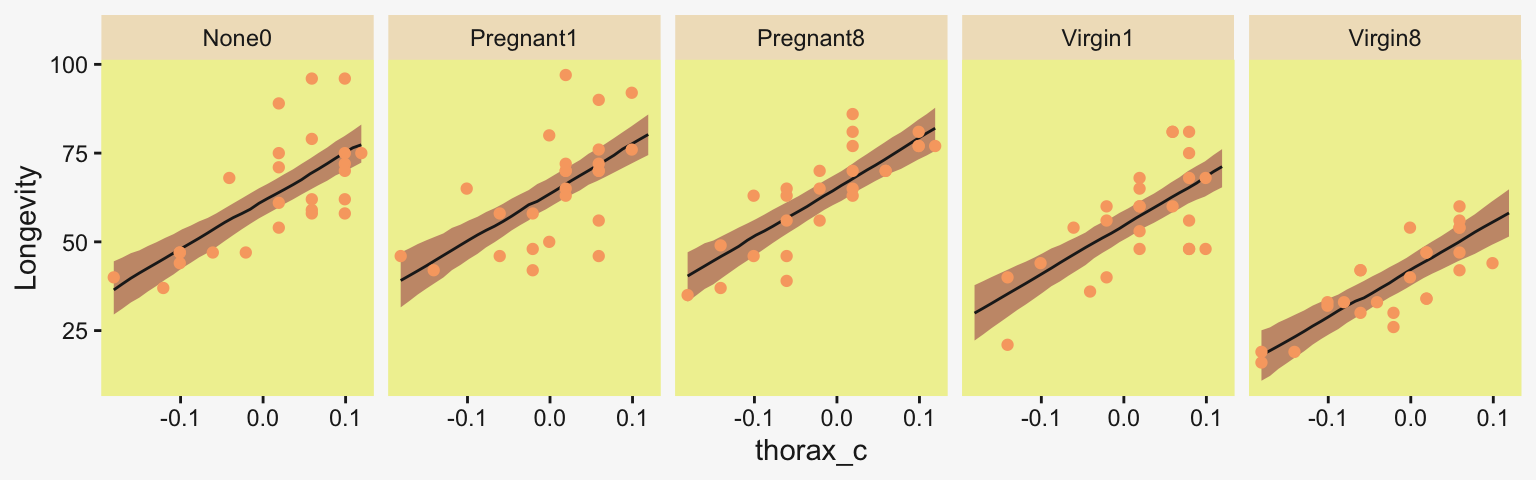

19.4 Including a metric predictor

“In Figure 19.3, the data within each group have a large standard deviation. For example, longevity values in the Virgin8 group range from \(20\) to \(60\) days” (p. 568). Turns out Kruschke’s slightly wrong on this. Probably just a typo.

my_data |>

group_by(CompanionNumber) |>

summarise(min = min(Longevity),

max = max(Longevity),

range = max(Longevity) - min(Longevity))# A tibble: 5 × 4

CompanionNumber min max range

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 None0 37 96 59

2 Pregnant1 42 97 55

3 Pregnant8 35 86 51

4 Virgin1 21 81 60

5 Virgin8 16 60 44But you get the point. For each group, there was quite a range. We might add predictors to the model to help account for those ranges.

The additional metric predictor is sometimes called a covariate. In the experimental setting, the focus of interest is usually on the nominal predictor (i.e., the experimental treatments), and the covariate is typically thought of as an ancillary predictor to help isolate the effect of the nominal predictor. But mathematically the nominal and metric predictors have equal status in the model. Let’s denote the value of the metric covariate for subject \(i\) as \(x_\text{cov}(i)\). Then the expected value of the predicted variable for subject \(i\) is

\[\mu(i) = \beta_0 + \sum_j \beta_{[j]} x_{[j]}(i) + \beta_\text{cov} x_\text{cov}(i)\]

with the usual sum-to-zero constraint on the deflections of the nominal predictor stated in Equation 19.2. In words, Equation 19.5 says that the predicted value for subject \(i\) is a baseline plus a deflection due to the group of \(i\) plus a shift due to the value of \(i\) on the covariate. (p. 569)

And the \(j\) subscript, recall, denotes group membership. In this context, it often

makes sense to set the intercept as the mean of predicted values if the covariate is re-centered at its mean value, which is denoted \(\overline x_\text{cov}\). Therefore Equation 19.5 is algebraically reformulated to make the baseline respect those constraints…. The first equation below is simply Equation 19.5 with \(x_\text{cov}\) recentered on its mean, \(\overline x_\text{cov}\). The second line below merely algebraically rearranges the terms so that the nominal deflections sum to zero and the constants are combined into the overall baseline:

\[\begin{align*} \mu & = \alpha_0 + \sum_j \alpha_{[j]} x_{[j]} + \alpha_\text{cov} (x_\text{cov} - \overline{x}_\text{cov}) \\ & = \underbrace{\alpha_0 + \overline{\alpha} - \alpha_\text{cov} \overline{x}_\text{cov}}_{\beta_0} + \sum_j \underbrace{(\alpha_{[j]} - \overline{\alpha})}_{\beta_[j]} x_{[j]} + \underbrace{\alpha_\text{cov}}_{\beta_{\text{cov}}} x_\text{cov} \\ & \text{where } \overline{\alpha} = \frac{1}{J} \sum^J_{j = 1} \alpha_{[j]} \end{align*}\] (pp. 569–570)

We have a visual depiction of all this in the hierarchical model diagram of Figure 19.4.

# Bracket

p1 <- tibble(x = 0.99,

y = 0.5,

label = "{_}") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[8], family = "Times", hjust = 1, size = 10) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0), limits = c(0, 1)) +

ylim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Plain arrow

p2 <- tibble(x = 0.71,

y = 1,

xend = 0.68,

yend = 0.25) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, xend = xend,

y = y, yend = yend)) +

geom_segment(arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Normal density

p3 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.45), y = 0.6,

hjust = c(0.5, 0),

label = c("italic(M)[0]", "italic(S)[0]"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Second normal density

p4 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.45), y = 0.6,

hjust = c(0.5, 0),

label = c("0", "sigma[beta]"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Third density

p5 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.45), y = 0.6,

hjust = c(0.5, 0),

label = c("italic(M)[italic(c)]", "italic(S)[italic(c)]"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Three annotated arrows

p6 <- tibble(x = c(0.09, 0.49, 0.9),

y = 1,

xend = c(0.20, 0.40, 0.64),

yend = 0) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, xend = xend,

y = y, yend = yend)) +

geom_segment(arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0.11, 0.42, 0.47, 0.74), y = 0.5,

label = c("'~'", "'~'", "italic(j)", "'~'"),

size = c(10, 10, 7, 10),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Likelihood formula

p7 <- tibble(x = 0.99,

y = 0.25,

label = "beta[0]+sum()[italic(j)]*beta['['*italic(j)*']']*italic(x)['['*italic(j)*']'](italic(i))+beta[italic(cov)]*italic(x)[italic(cov)](italic(i))") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", hjust = 1, parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0), limits = c(0, 1)) +

ylim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Half-normal density

p8 <- tibble(x = seq(from = 0, to = 3, by = 0.01)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.2,

label = "half-normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 1.5, y = 0.6,

label = "0*','*~italic(S)[sigma]",

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Annotated arrow

p9 <- tibble(x = 0.38,

y = 0.65,

label = "'='") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 10) +

geom_segment(x = 0.5, xend = 0.5,

y = 1, yend = 0.25,

arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# The fourth normal density

p10 <- tibble(x = seq(from = -3, to = 3, by = 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = (dnorm(x)) / max(dnorm(x)))) +

geom_area(fill = pp[9]) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = 0, y = 0.2,

label = "normal",

color = pp[4], size = 7) +

annotate(geom = "text",

x = c(0, 1.45), y = 0.6,

hjust = c(0.5, 0),

label = c("mu[italic(i)]", "sigma[italic(y)]"),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

scale_x_continuous(expand = c(0, 0)) +

theme_void() +

theme(axis.line.x = element_line(color = pp[4], linewidth = 0.5))

# Another annotated arrow

p11 <- tibble(x = 0.5,

y = 0.6,

label = "'~'") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 10) +

geom_segment(x = 0.85, xend = 0.27,

y = 1, yend = 0.2,

arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# The final annotated arrow

p12 <- tibble(x = c(0.375, 0.625),

y = c(1/3, 1/3),

label = c("'~'", "italic(i)")) |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(size = c(10, 7),

color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE) +

geom_segment(x = 0.5, xend = 0.5,

y = 1, yend = 0,

arrow = my_arrow, color = pp[4]) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Some text

p13 <- tibble(x = 0.5,

y = 0.5,

label = "italic(y[i])") |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, y = y, label = label)) +

geom_text(color = pp[4], family = "Times", parse = TRUE, size = 7) +

xlim(0, 1) +

theme_void()

# Define the layout

layout <- c(

area(t = 1, b = 1, l = 6, r = 7),

area(t = 2, b = 3, l = 6, r = 7),

area(t = 3, b = 4, l = 1, r = 3),

area(t = 3, b = 4, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 3, b = 4, l = 9, r = 11),

area(t = 6, b = 7, l = 1, r = 9),

area(t = 5, b = 6, l = 1, r = 11),

area(t = 6, b = 7, l = 11, r = 13),

area(t = 9, b = 10, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 8, b = 9, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 8, b = 9, l = 5, r = 13),

area(t = 11, b = 11, l = 5, r = 7),

area(t = 12, b = 12, l = 5, r = 7))

# Combine, adjust, and display

(p1 + p2 + p3 + p4 + p5 + p7 + p6 + p8 + p10 + p9 + p11 + p12 + p13) +

plot_layout(design = layout) &

ylim(0, 1) &

theme(plot.margin = margin(0, 5.5, 0, 5.5))

19.4.1 Example: Sex, death, and size

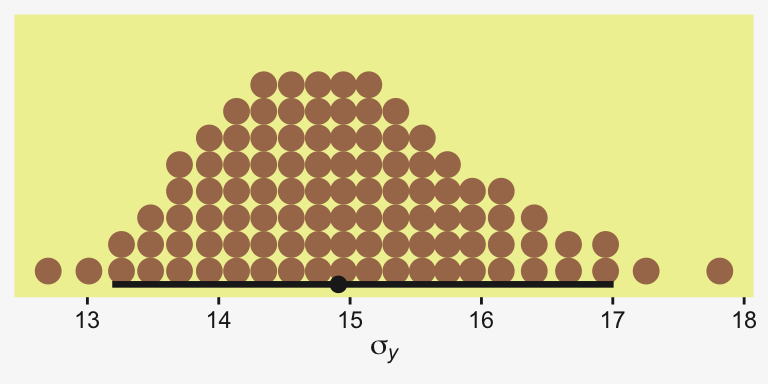

Kruschke recalled fit19.1’s estimate for \(\sigma_y\) had a posterior mode around 14.8. Let’s confirm with a plot.

as_draws_df(fit19.1) |>

ggplot(aes(x = sigma)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab(expression(sigma[italic(y)])) +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank())

Yep, that looks about right. That large of a difference in days would indeed make it difficult to detect between-group differences if those differences were typically on the scale of just a few days. Since Thorax is moderately correlated with Longevity, including Thorax in the statistical model should help shrink that \(\sigma_y\) estimate, making it easier to compare group means. Following the sensibilities from the equations just above, here we’ll mean-center our covariate, first.

my_data <- my_data |>

mutate(thorax_c = Thorax - mean(Thorax))

head(my_data)# A tibble: 6 × 4

Longevity CompanionNumber Thorax thorax_c

<dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 35 Pregnant8 0.64 -0.181

2 37 Pregnant8 0.68 -0.141

3 49 Pregnant8 0.68 -0.141

4 46 Pregnant8 0.72 -0.101

5 63 Pregnant8 0.72 -0.101

6 39 Pregnant8 0.76 -0.0610Our model code follows the structure of that in Kruschke’s Jags-Ymet-Xnom1met1-MnormalHom-Example.R and Jags-Ymet-Xnom1met1-MnormalHom.R files. As a preparatory step, we redefine the values necessary for stanvars.

(mean_y <- mean(my_data$Longevity))[1] 57.44(sd_y <- sd(my_data$Longevity))[1] 17.56389(sd_thorax_c <- sd(my_data$thorax_c))[1] 0.07745367omega <- sd_y / 2

sigma <- 2 * sd_y

(s_r <- gamma_a_b_from_omega_sigma(mode = omega, sd = sigma))$shape

[1] 1.283196

$rate

[1] 0.03224747stanvars <- stanvar(mean_y, name = "mean_y") +

stanvar(sd_y, name = "sd_y") +

stanvar(sd_thorax_c, name = "sd_thorax_c") +

stanvar(s_r$shape, name = "alpha") +

stanvar(s_r$rate, name = "beta")Now we’re ready to fit the brm() model, our hierarchical alternative to ANCOVA.

fit19.5 <- brm(

data = my_data,

family = gaussian,

Longevity ~ 1 + thorax_c + (1 | CompanionNumber),

prior = c(prior(normal(mean_y, sd_y * 5), class = Intercept),

prior(normal(0, 2 * sd_y / sd_thorax_c), class = b),

prior(gamma(alpha, beta), class = sd),

prior(cauchy(0, sd_y), class = sigma)),

iter = 4000, warmup = 1000, chains = 4, cores = 4,

seed = 19,

control = list(adapt_delta = 0.99),

stanvars = stanvars,

file = "fits/fit19.05")Here’s the model summary.

print(fit19.5) Family: gaussian

Links: mu = identity

Formula: Longevity ~ 1 + thorax_c + (1 | CompanionNumber)

Data: my_data (Number of observations: 125)

Draws: 4 chains, each with iter = 4000; warmup = 1000; thin = 1;

total post-warmup draws = 12000

Multilevel Hyperparameters:

~CompanionNumber (Number of levels: 5)

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sd(Intercept) 13.88 7.45 6.02 33.61 1.00 2552 3470

Regression Coefficients:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept 57.72 7.21 43.64 71.68 1.00 2549 3045

thorax_c 135.86 12.40 111.34 160.56 1.00 6904 6947

Further Distributional Parameters:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

sigma 10.60 0.69 9.34 12.06 1.00 7607 6752

Draws were sampled using sampling(NUTS). For each parameter, Bulk_ESS

and Tail_ESS are effective sample size measures, and Rhat is the potential

scale reduction factor on split chains (at convergence, Rhat = 1).Let’s see if that \(\sigma_y\) posterior shrank.

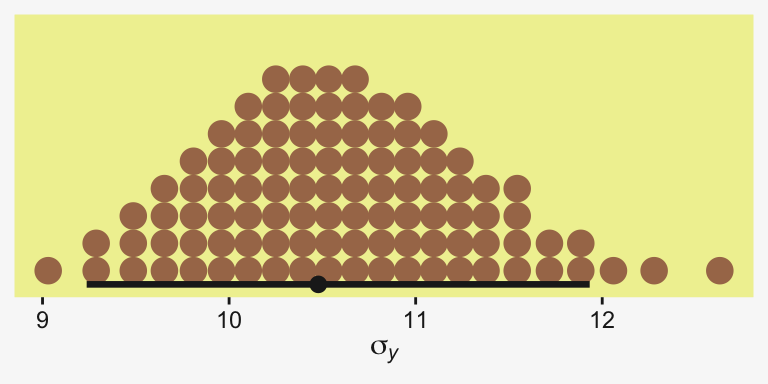

as_draws_df(fit19.5) |>

ggplot(aes(x = sigma)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

xlab(expression(sigma[italic(y)]))

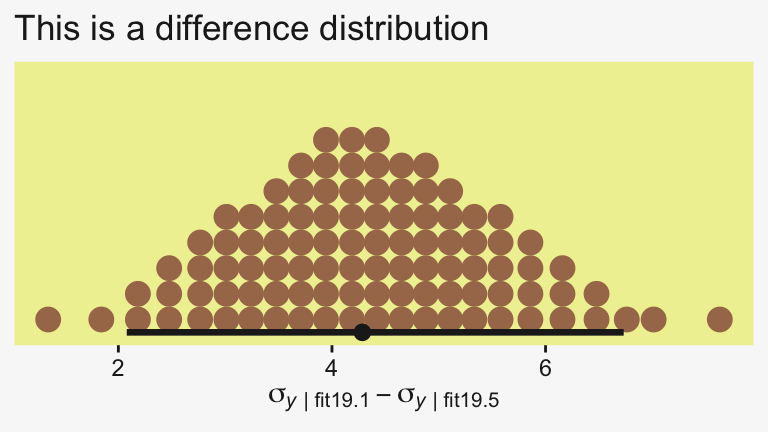

Yep, sure did! Now our between-group comparisons should be more precise. Heck, if we wanted to we could even make a difference plot for the \(\sigma_y\) posteriors.

tibble(sigma1 = as_draws_df(fit19.1) |> pull(sigma),

sigma5 = as_draws_df(fit19.5) |> pull(sigma)) |>

transmute(dif = sigma1 - sigma5) |>

ggplot(aes(x = dif)) +

stat_dotsinterval(point_interval = mode_hdi, .width = 0.95,

color = pp[4], quantiles = 100,

slab_fill = pp[5], slab_size = 0) +

scale_y_continuous(NULL, breaks = NULL) +

labs(x = expression(sigma[italic(y)][" | fit19.1"]-sigma[italic(y)][" | fit19.5"]),

title = "This is a difference distribution")

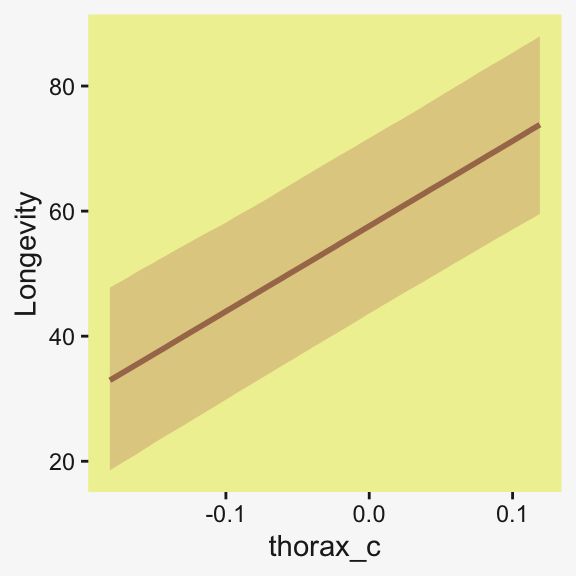

If you want a quick and dirty plot of the relation between thorax_c and Longevity, you might employ brms::conditional_effects().

conditional_effects(fit19.5) |>

plot(line_args = list(color = pp[5], fill = pp[11]))Ignoring unknown labels:

• fill : "NA"

• colour : "NA"

Ignoring unknown labels:

• fill : "NA"

• colour : "NA"

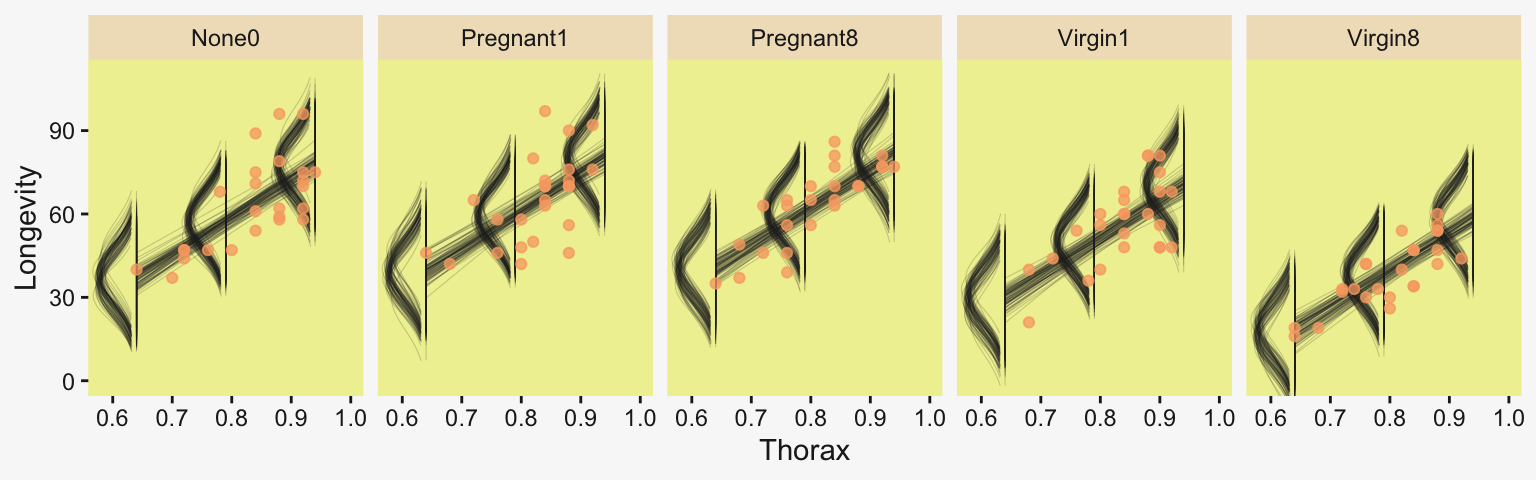

But to make plots like the ones at the top of Figure 19.5, we’ll have to work a little harder. First, we need some intermediary values marking off the three values along the Thorax-axis Kruschke singled out in his top panel plots. As far as I can tell, they were the min(), the max(), and their mean().

(r <- range(my_data$Thorax))[1] 0.64 0.94mean(r)[1] 0.79Next, we’ll make the data necessary for our side-tipped Gaussians. For kicks and giggles, we’ll choose 80 draws instead of 20. But do note how we used our r values, from above, to specify both Thorax and thorax_c values in addition to the CompanionNumber categories for the newdata argument. Otherwise, this workflow is very much the same as in previous plots.

n_draws <- 80

densities <- my_data |>

distinct(CompanionNumber) |>

expand_grid(Thorax = c(r[1], mean(r), r[2])) |>

mutate(thorax_c = Thorax - mean(my_data$Thorax)) |>

add_epred_draws(fit19.5, ndraws = n_draws, seed = 19, dpar = c("mu", "sigma")) |>

mutate(ll = qnorm(0.025, mean = mu, sd = sigma),

ul = qnorm(0.975, mean = mu, sd = sigma)) |>

mutate(Longevity = map2(.x = ll, .y = ul, .f = \(ll, ul) seq(from = ll, to = ul, length.out = 100))) |>

unnest(Longevity) |>

mutate(density = dnorm(x = Longevity, mean = mu, sd = sigma))

glimpse(densities)Rows: 120,000

Columns: 14

Groups: CompanionNumber, Thorax, thorax_c, .row [15]

$ CompanionNumber <chr> "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", …

$ Thorax <dbl> 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.…

$ thorax_c <dbl> -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.1…

$ .row <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ .chain <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .iteration <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .draw <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ .epred <dbl> 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.1…

$ mu <dbl> 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.17164, 39.1…

$ sigma <dbl> 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.60219, 11.6…

$ ll <dbl> 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.43175, 16.4…

$ ul <dbl> 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.91152, 61.9…

$ Longevity <dbl> 16.43175, 16.89114, 17.35054, 17.80993, 18.26932, 18.72871, 19.18810, 19.64749, 20.10689, 20.56628, 21.0…

$ density <dbl> 0.005037415, 0.005439648, 0.005864798, 0.006313270, 0.006785390, 0.007281391, 0.007801409, 0.008345471, …Here, we’ll use a simplified workflow to extract the fitted() values in order to make the regression lines. Since these are straight lines, all we need are two values for each draw, one at the extremes of the Thorax axis.

f <- my_data |>

distinct(CompanionNumber) |>

expand_grid(Thorax = c(r[1], mean(r), r[2])) |>

mutate(thorax_c = Thorax - mean(my_data$Thorax)) |>

add_epred_draws(fit19.5, ndraws = n_draws, seed = 19, value = "Longevity")

glimpse(f)Rows: 1,200

Columns: 8

Groups: CompanionNumber, Thorax, thorax_c, .row [15]

$ CompanionNumber <chr> "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", "Pregnant8", …

$ Thorax <dbl> 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.64, 0.…

$ thorax_c <dbl> -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.18096, -0.1…

$ .row <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,…

$ .chain <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .iteration <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

$ .draw <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 2…

$ Longevity <dbl> 39.17164, 38.72720, 41.58792, 39.72092, 44.90579, 34.93792, 44.02521, 43.36934, 42.00286, 42.27404, 38.6…Now we’re ready to make our plots for the top row of Figure 19.3.

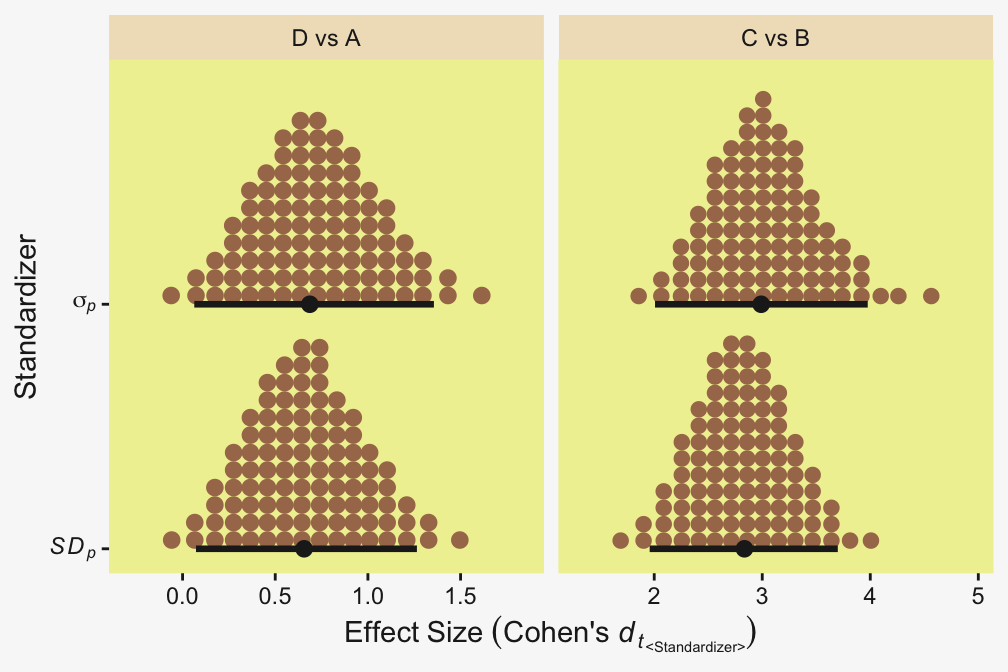

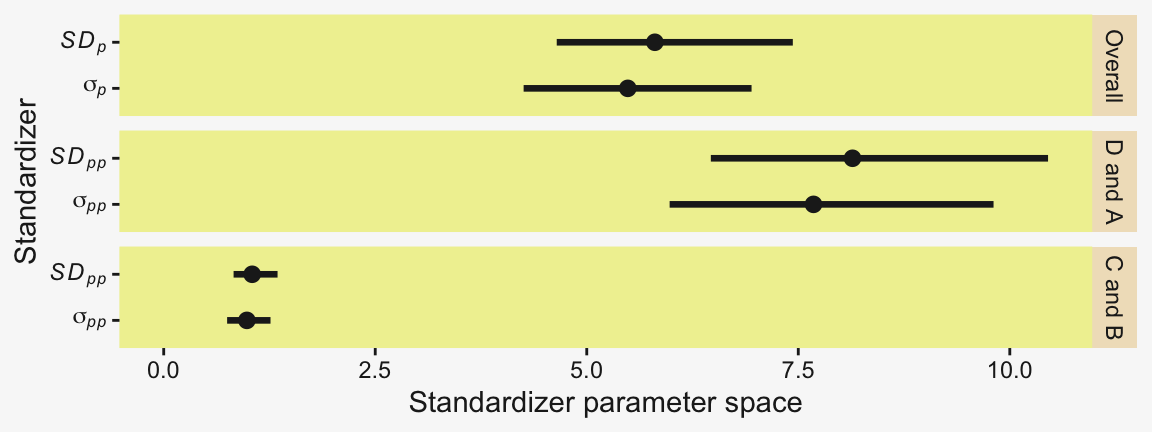

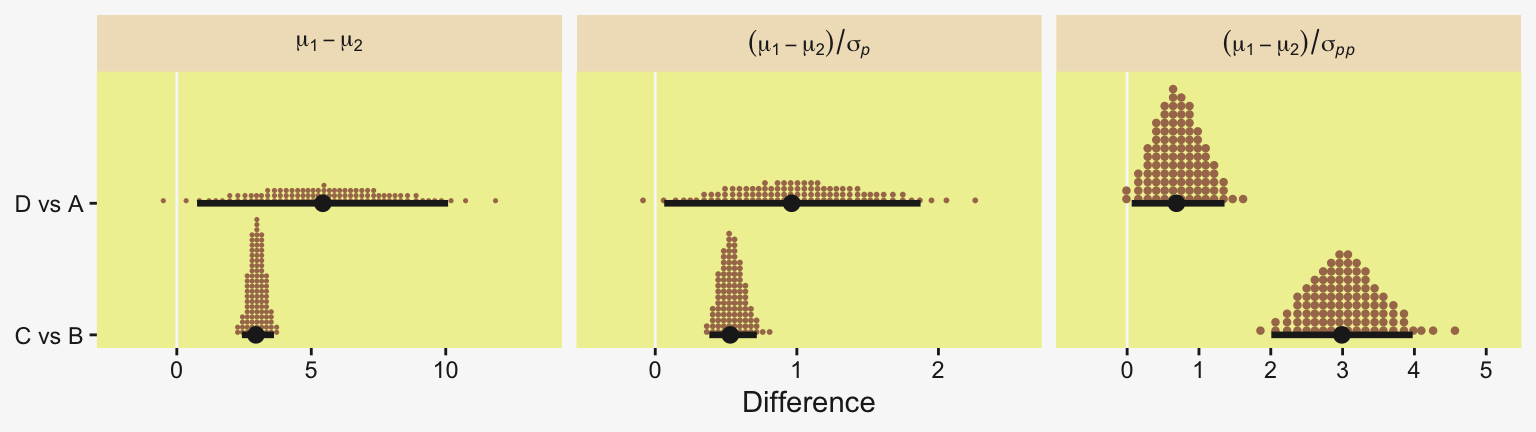

densities |>

ggplot(aes(x = Longevity, y = Thorax)) +

# The Gaussians

geom_ridgeline(aes(height = -density, group = interaction(Thorax, .draw)),

color = adjustcolor(pp[4], alpha.f = 1/5), fill = NA,

linewidth = 1/5, min_height = NA, scale = 5/3) +

# The vertical lines below the Gaussians

geom_line(aes(group = interaction(Thorax, .draw)),

alpha = 1/5, color = pp[4], linewidth = 1/5) +

# The regression lines

geom_line(data = f,

aes(group = .draw),

alpha = 1/5, color = pp[4], linewidth = 1/5) +

# The data

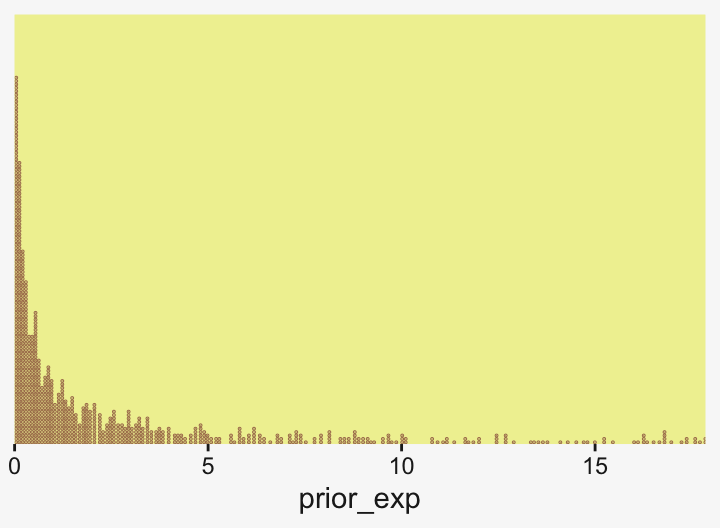

geom_point(data = my_data,