Rows: 262

Columns: 7

$ tenure <dbl> 1.67, 0.58, 0.58, 2.00, 5.00, 9.00, 0.00, 2.50, 0.50, 0.58, 9.00, 1.92, 2.00, 1.42, 0.92, 20.00, 2.00, 10.00, 0…

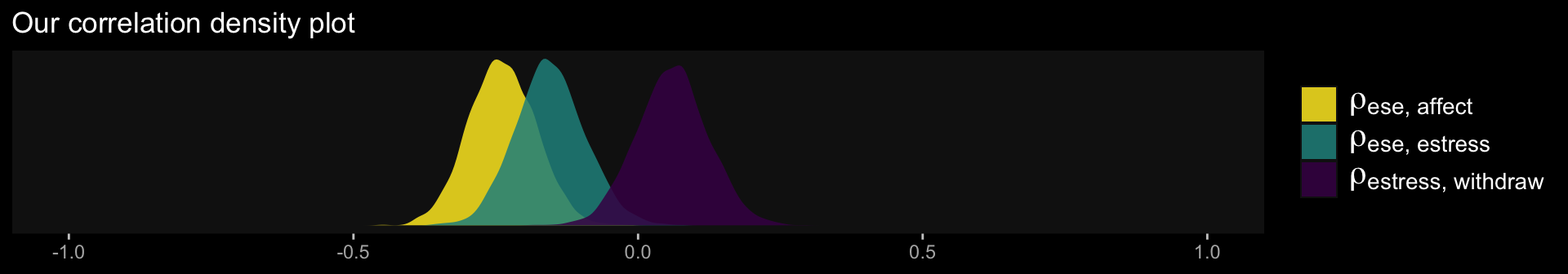

$ estress <dbl> 6.0, 5.0, 5.5, 3.0, 4.5, 6.0, 5.5, 3.0, 5.5, 6.0, 5.5, 4.0, 3.0, 2.5, 3.5, 6.0, 4.0, 6.0, 3.5, 4.0, 2.5, 4.0, 2…

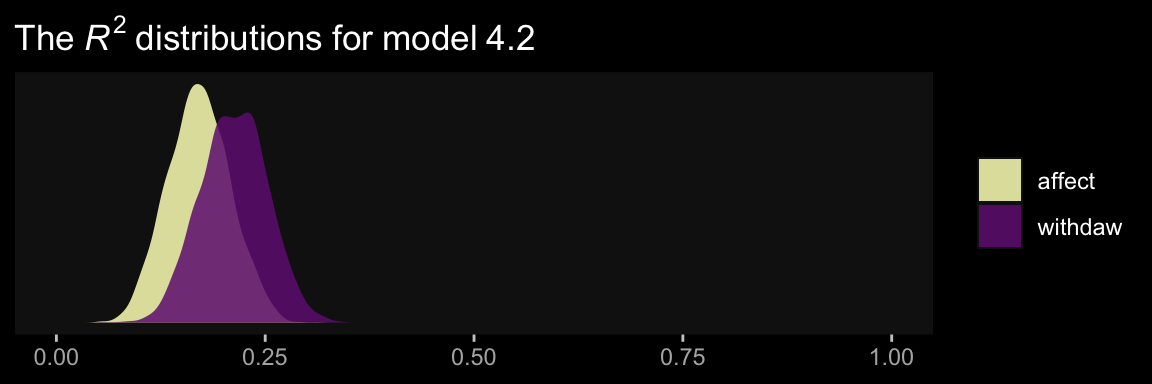

$ affect <dbl> 2.60, 1.00, 2.40, 1.16, 1.00, 1.50, 1.00, 1.16, 1.33, 3.00, 3.00, 2.00, 1.83, 1.16, 1.16, 1.00, 1.33, 1.50, 1.3…

$ withdraw <dbl> 3.00, 1.00, 3.66, 4.66, 4.33, 3.00, 1.00, 1.00, 2.00, 4.00, 4.33, 1.00, 5.00, 1.66, 4.00, 1.33, 1.66, 1.66, 2.0…

$ sex <dbl> 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, …

$ age <dbl> 51, 45, 42, 50, 48, 48, 51, 47, 40, 43, 57, 36, 33, 29, 33, 48, 40, 45, 37, 42, 54, 57, 37, 49, 40, 30, 49, 31,…

$ ese <dbl> 5.33, 6.05, 5.26, 4.35, 4.86, 5.05, 3.66, 6.13, 5.26, 4.00, 2.53, 6.60, 5.20, 5.66, 5.66, 5.40, 6.00, 6.13, 5.4…

Comments